The last person to lift the Stanley Cup in Toronto was an unknown thief who swiped the trophy from the Sports Hall of Fame in December, 1970. Though shocking, the incident was actually the third successful silverware heist on the NHL within two years. Over a 20-month period, various Toronto crooks swiped the Conn Smythe, Calder, Hart, and William Masterton trophies, a historic piece of the original Stanley Cup, and, finally, the Stanley Cup itself.

It would take seven years for police to recover everything.

Purchased in 1892 by Governor-General Lord Stanley of Preston as a prize for the top amateur hockey team in Canada, the original Stanley Cup—a silver rose bowl made in Sheffield, England—was engraved with the words “Dominion Hockey Challenge Cup” and “From Stanley of Preston.”

Interestingly, Stanley didn’t commission a unique design for his famous gift—there are thousands of identical silver rose bowls in the U.K., according to the Toronto Star.

For several years, the Challenge Cup was awarded to the team the trustees of the cup judged the best in Canada. Later, the format was changed to include a playoff between various amateur leagues before the National Hockey League became the dominant competition and the de facto holder of the cup.

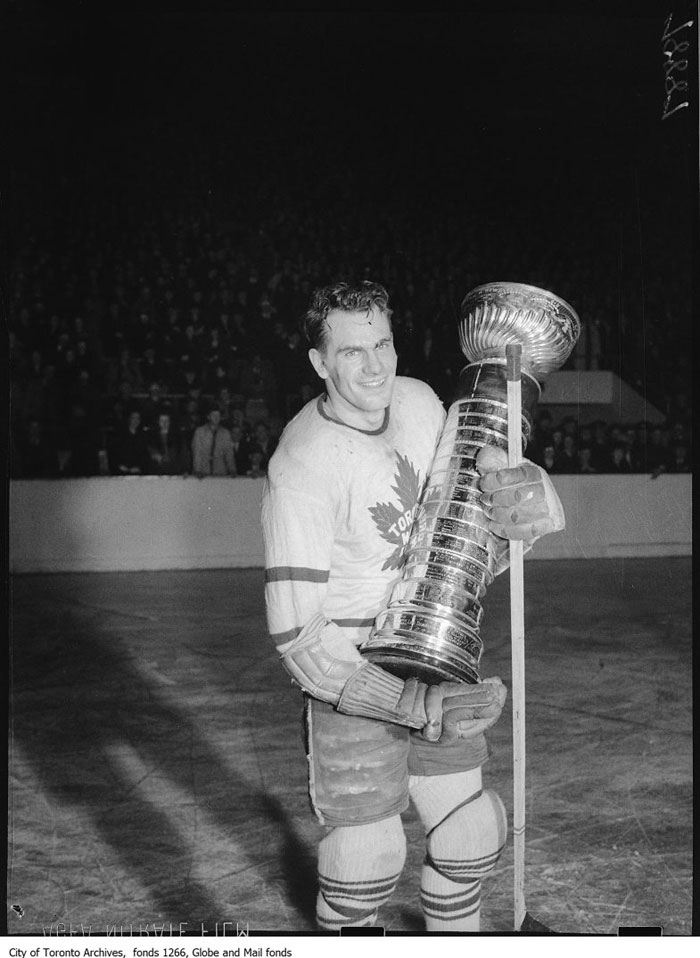

The 1906-07 Montreal Wanderers were the first team to engrave their names on the cup, but marking the trophy didn’t become an annual tradition until 1924. With space at a premium, the cup trustees added a metal collar to the base. Every few years, they added a new silver ring, making the trophy tall and thin. Players nicknamed it the “stovepipe cup” for its resemblance to a wood stove exhaust.

To prevent the trophy continuing to grow, the NHL commissioned the modern version of the cup in 1948. The top of the metal collar containing the names of the earliest cup winners was removed and attached to a new base with five wider rings, giving the Stanley Cup it’s unique shape.

When not in use, the NHL kept the cup, the conference trophies, and various player awards on public display at the Sports Hall of Fame at Exhibition Place.

On April 9, 1969, thieves forced in the front door of the Sports Hall of Fame and stole the Conn Smythe, Calder, and Hart trophies by smashing a display case with a shovel, but missed out on the Stanley Cup, which was away for maintenance. Bizarrely, the crooks declined to swipe the Prince of Wales, Norris, Lady Byng, and Art Ross trophies from the same broken case.

NHL commissioner Clarence Campbell said the league would commission new versions of the trophies from Carl Petersen, the Montreal silversmith who created the originals. “The tragedy of this thing, to me, is that the trophies have absolutely no value to anyone except their worth in metal,” he said. Their was no ransom.

Luckily, it didn’t come to that. A few days later, on April 11, an anonymous phone tip led police to a garage on Judson St. in Etobicoke, where the trophies and several skating medals were recovered undamaged. Detective Harold Lambert said the thieves probably found the trophies too hot to handle and used a middleman to orchestrate the return.

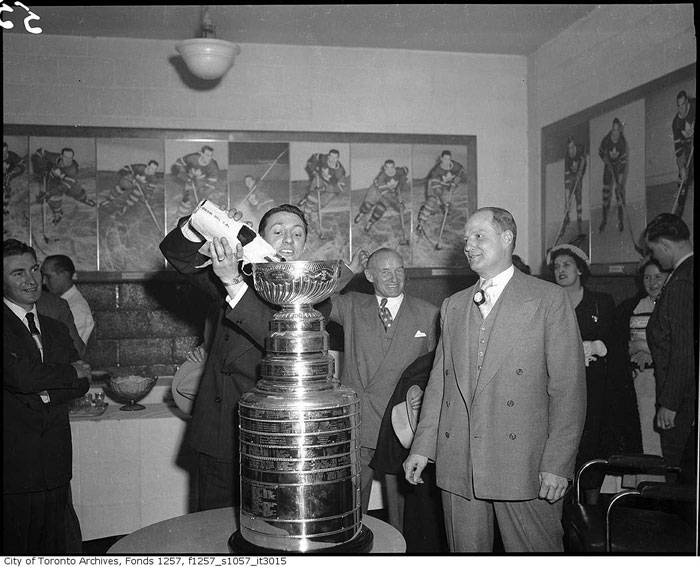

Despite promising to beef up security around hockey’s hallowed silverware, there was another theft at the Hall of Fame in 1970. This time, crooks made off with the Stanley Cup collar—the three rings below the original bowl—containing the engraved names of the 1923-24, 1924-25, and 1925-26 champions.

It took several days for Hall of Fame curator Maurice Reid to notice the piece was missing from a special miniature display case. This time, it appeared the thief had simply deposited the unguarded 20 lb piece of silverware in a bag during regular visitor hours.

Worse was still to come. On Dec. 6, 1970, the Stanley Cup vanished along with the Conn Smythe and William Masterton trophies—the third successful heist in 20 months. A hyper-sensitive new alarm system, one that a mouse accidentally triggered earlier in the year, failed to sound because construction workers digging outside had accidentally damaged a critical wire.

“The bad joke going the rounds is that the Toronto Maple Leafs stole the Stanley Cup on Saturday because they won’t get it any other way,” the Globe and Mail quipped. Maurice Reid wasn’t laughing. The method of entry—a busted lock—resembled that of the April break-in that resulted in the brief loss of the Conn Smythe, Calder, and Hart trophies. Apart from that, cops had little to go on.

The next day, the NHL’s Clarence Campbell crushed the thieves’ elation. The original Stanley Cup, he said, was safe in a bank vault. The oldest parts of the trophy had become too brittle to be safely manhandled by celebrating hockey players, so the league had commissioned an identical presentation cup teams could fill with champagne or drop on the ground.

The cup wasn’t available to thieves in April, 1969 because silversmiths in Montreal were busily recreating the original. “We have all the original parts of the Stanley Cup except a couple of bands,” Campbell said. “So nothing of historic value is missing.”

Still, Metro police Detective Harold Lambert was once again ready for a ransom demand.

A call did come in to Metro police, but it was Det. Sgt. Wallace Harkness, the head of the Metro police complaints bureau, who answered. The woman on the other end said the gang who had taken the cup intended to drop it in Lake Ontario unless their friend, in prison on a “serious robbery charge,” was released.

Harkness laughed off the threat, but he was nervous. Replica or not, losing the cup in the lake would be a desecration of hockey’s greatest prize. “That’s like burning the flag,” Harkness told the press. By now, the thieves knew they had taken an practically worthless replica they couldn’t sell without arousing suspicion.

On Dec. 23, 1970, roughly three weeks after the cup vanished, Harkness woke to a sound outside his home on Presteign Ave. in East York. “We heard a noise and looked out,” he said. “and there they were between the car and the house.” The thieves had abandoned the Stanley Cup, Conn Smythe, and William Masterton trophies on the ground and fled.

The safe return was a major relief for Hall of Fame curator Maurice Reid. “There have been so many jokes that I was getting to feel like slugging somebody,” he told the Globe and Mail. “[I] didn’t go to hockey games or anything; stayed home as much as I could.”

He still didn’t know why the alarm system had failed, but he vowed to add even more security measures.

However, the collar of the original cup—a genuine piece of hockey history—was still missing, and it would stay that way for another seven years.

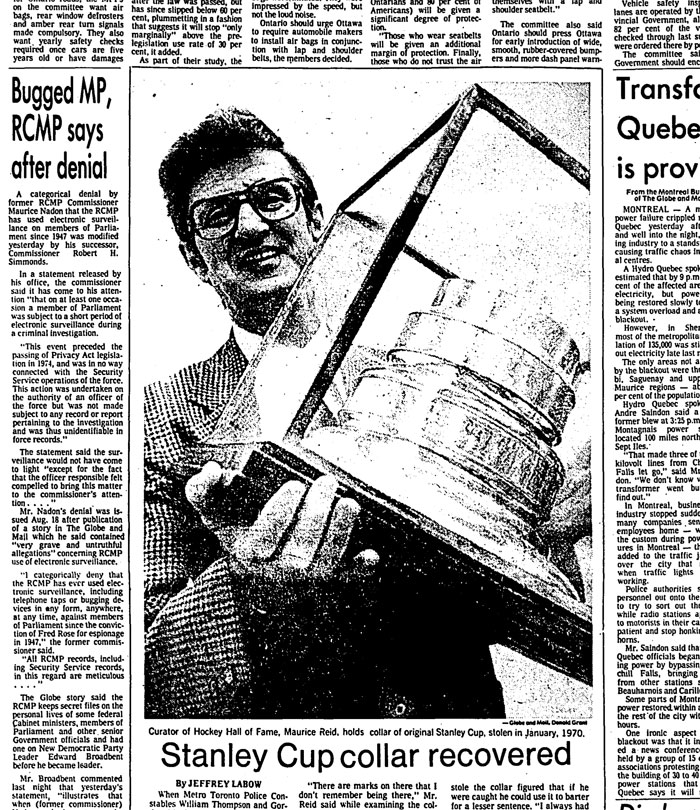

In Sept., 1977, police constables William Thompson and Gordon Black, dispatched to a Toronto cleaning store, radioed a strange messing to their sergeant, Robert Morrison, at 54 Division. They said they had found a piece of the Stanley Cup wrapped in brown paper. “Are you crazy?,” Morrison said.

Closer inspection revealed the metal rings containing the names of NHL greats like Jack Adams and Cecil Hart were genuine. “It’s been around the criminal underworld. Several people have had it and the cleaning store is where it came to rest,” said Sgt. Morrison. “It looked like a Christmas package when we picked it up.”

Apart from a few minor dings, the 50-year-old piece of silver was still in good condition. Although a man was arrested and charged with possession of stolen property, it was never proven who actually took the collar in the first place. Sgt. Morrison had suspicions, but there were no arrests.

The collar was handed back to a relieved Maurice Reid at the Hall of Fame, ending an a seven-year battle to regain various pieces of hockey history.

“I always had confidence we would get it back,” he said. “It’s really no good to anyone else.”