EDITOR’S NOTE: This piece was written in 1985 by Stephen Otto for a catalog that was never published to accompany the exhibit “Meeting Places: Toronto’s City Halls,” at the Market Gallery. It is offered here to mark Toronto’s 182nd anniversary of incorporation on March 6, and to foster understanding of the North St. Lawrence Market site where archaeological excavations are taking place currently prior to the redevelopment of the property for courts and a new market.

In July 1833 the Colonial Advocate took notice of the increased pace of commerce and improvements in York: “everything is going on charmingly … In short York bids fair to become one of the first cities of importance, for commerce, extent and neatness, in British America.”

That year the assessors counted 6,094 people, a startling increase over the 2,860 residents in 1830 when the Home District magistrates had advertised for plans to be submitted by early June for a new brick market hall, “about one hundred feet by forty” in size. When completed two years later, the Town Hall and market building was the largest structure erected in the capital of Upper Canada. A visitor noted it had, “no equal of the kind even in New York or in the States.” The lofty Town Hall was prominent along the south side of King Street, while the market structure with its monumental archways into the square was a major element in the panorama of York seen from the lake. Their scale seemed better suited to a much larger place, which York was rapidly becoming.

The market hall was to be sited on the eastern end of the market reserve, a generous space of five and a half acres bounded by the present Front, Church, King, and Jarvis Streets. It would replace a wooden building housing 22 butchers, which in 1828 had attracted the notice of George Henry, author of The Emigrant’s Guide, or Canada as it is. “The present market house, which is extensive,” he said, “appears scarcely large enough to accommodate the inhabitants of this fast increasing town.” This temple to lean trim and fair weight was surrounded by farmers selling butter, eggs, fruits, vegetables, grains, wood and hay from their wagons. After the magistrates examined the plans and estimates sent in they had second thoughts, perhaps about the suggested dimensions or the anticipated costs of such a building. In any event, new instructions must have been given to builders and architects because several months later, in January 1831, five fresh proposals were ready to be considered. These were narrowed down to two and a committee was appointed to confer with the authors, James G. Chewett and James Cooper, “in explanation of their plans.”

Until later, no professional architects existed in York. Chewett, who was well known to members of the committee, had been trained as a land surveyor and draftsman by his father, the deputy Surveyor General for Upper Canada. He is known to have prepared occasional designs, although it is uncertain which of these, if any, were built. Cooper was a less familiar figure. Possibly he was a builder, the “Mr. Cooper” whose designs were adopted for St. Andrew’s Presbyterian Church at Niagara in early 1831.

In March, the Home District magistrates made their selection, approving James Cooper’s plans and awarding him the winner’s premium of £25. His scheme departed significantly from the rectangular hall called for in 1830. Instead, he proposed a continuous row of two-storey brick buildings enclosing an open marketplace only slightly smaller than a football field, laid out north and south on a site that sloped down gently from King Street to Front Street. The interior square could be entered through three lofty arched wagonways – on the west, south and east – and several pedestrian passages. Inside there were thirty-six butchers’ stalls down the two long sides; flanking the south arch were places for sellers of butter, eggs and cheese. Outside this archway four shops faced Front Street. At the south end above the shops, and along the sides over the stalls, were ten long rooms or granaries, reached from broad wooden galleries surrounding the inside of the square.

Ill. 1: In 1985 Ryerson students spent some 500 hours building this model of the Town Hall and market, seen from the King Street end. (Market Gallery Collection, neg. #1985-237-16)

At the north end of the quadrangle, a passageway from King Street emerged from beneath the Town Hall. Cooper’s original design has been lost, but one of the few changes to his proposal made during construction was to enlarge this entrance to form a high, open, triple-arched arcade. Eventually fruit and vegetable sellers would take up their places here, giving rise to a steady stream of complaints about the untidiness of the market’s main entrance. Perched above the arcade, the Town Hall was taller than its adjoining wings and stood several feet nearer to the street. Each wing contained a first-class shop on King Street and comfortable walk-up quarters on the second floor. The Town Hall was a rather plain example of the Georgian builder’s art. On the second floor a trio of large rectangular windows looked over the street, and above them the gable of the building was expressed as a deep, bracketed pediment, giving the Town Hall additional prominence.

From the outside the market structure resembled nothing so much as a defensible farmstead of the Middle Ages – one erected in straight-forward style using “staring red brick” as the writer Anna Jameson described the favoured local building material. Great wooden gates closed the wagonways after market hours, and below the second storey the long exterior side walls were broken only by narrow “loopholes” that ventilated the butchers’ stalls.

The York Market differed in its plan from most other markets in British North America or the north-eastern United States. Elsewhere the market structure was usually surrounded by the marketplace. Depending on the size of the town it might be a simple wooden shelter, a larger open-sided building accommodating butchers’ stalls, or an enclosed hall. In York the buildings enclosed the square. Cooper may have been influenced in his choice of plan by the new Covent Garden and Hungerford Markets in London, both designed by the architect Charles Fowler. Proposals for the Covent Garden Market had been exhibited in 1827; the building itself was completed by 1830.

In the United States where many substantial market houses existed, there might be a public room over the market. The Town Hall at York followed that example. The space was intended, however, to serve neither as a courtroom, the traditional use elsewhere, nor as a municipal seat in anticipation of York’s incorporation as the City of Toronto. Instead, it was expected to relieve a shortage of places for social gatherings, public assemblies, concerts and meetings. While rooms could always be rented at inns and the Freemasons’ Hall, often they were not large enough.

No particular need existed in York for a hall associated with local government. Town meetings were held only once a year, usually in one of the inns, to nominate officials with limited civic duties for the ensuing term – assessors, clerks, collectors, pathmasters, poundmasters, and wardens. The nominations had to be approved by the district magistrates who were named by the Lieutenant Governor and exercised all authority at the local level. Among other responsibilities, they levied and collected taxes, supervised the statute labour required of property owners for the upkeep of roads, built and maintained bridges, courthouses, jails and markets, and licensed taverns. Normally, the magistrates met in the District Court House and required no other special offices or chambers.

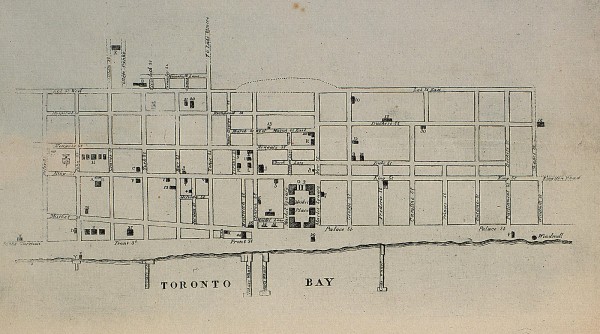

Ill. 2: This map of Toronto was made by Alpheus Todd, then only 13 years of age, short weeks after Toronto became a city in March, 1834. Note the prominence of the market square which occupied a whole block. (Toronto Public Library, T1834/4Msm)

The legislature passed a bill in March 1831 to clear away lingering doubts about ownership of the square. Construction on the market was expected to be under way during the summer and to cost £6,500. When tenders were called, only one bid was received, likely for more than the anticipated cost, from James Cooper, the building’s designer, and Joseph Turton, a York mason. After the deadline was extended a month several more bids were submitted and on July 21 one from William Allan of Kingston was accepted by the magistrates. The Building Committee was authorized to retain a superintendent at a rate not to exceed three per cent, so it hired Duncan Kennedy and his partner Peter McArthur, experienced contractors responsible for building the Brock Monument on Queenston Heights in 1824-27 and the Bank of Upper Canada at York in 1825-27.

In September 1831 the old market house was skidded off its site, and Allan’s labourers began digging the foundations and cellars. Late that fall and early the next spring, construction was pushed ahead. It went quickly and without much notice. In December 1832, following a final inspection of the building by Kennedy and McArthur, the magistrates took it over except for the unfinished Town Hall. Some of the more important shops had been leased already, including the easterly store on King Street which was already being stocked by Gillespie, Jamieson & Co., a branch of one of Montreal’s largest wholesaling houses. The rest of the butchers’ stalls, shops and granaries were advertised for rent a few days before Christmas.

In the spring, the area on King Street in front of the Town Hall was paved with Kingston limestone, the marketplace was levelled, and flagstones were laid to form a walkway around the edge. Probably the centre of the square was surfaced with rubble stone. When all work was completed including the Town Hall in August 1833, the total cost of the project had reached £9,400, most of which was borrowed from the Bank of Upper Canada and secured by market rents and fees.

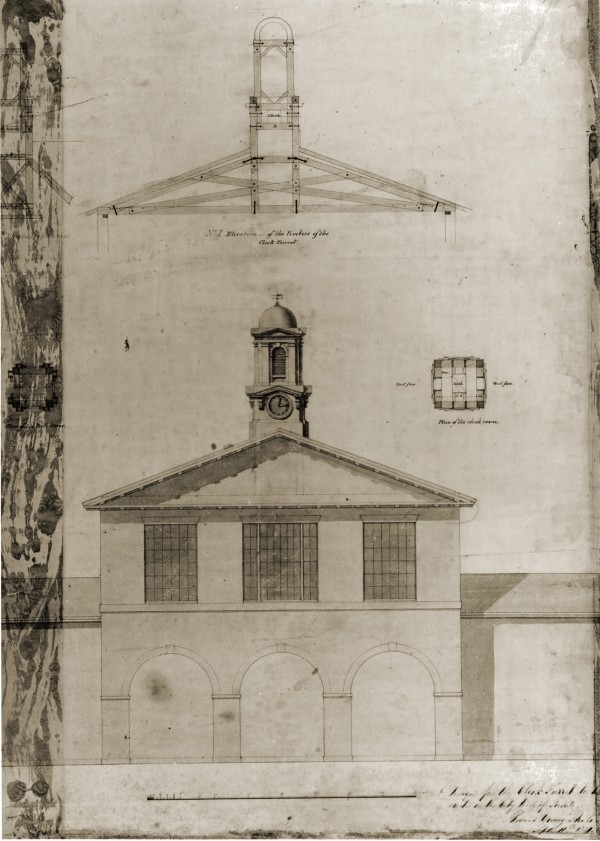

Ill. 3: In September, 1841, architect Thomas Young proposed a design for a clock turret on the City Hall, but it was never erected. (City of Toronto Archives, Series 1092, item 6)

* * * * * * * * * *

One of the first events in the Town Hall, the York Annual Bazaar, took place in October, 1833, under the patronage of Lady Colborne. The hall was one large room, about 50 feet square and 20 feet high, warmed by two large fireplaces on the side walls. It was accessed from King Street by staircases in the adjacent wings. Approval to use the hall had to be secured from the district magistrates. According to William Lyon Mackenzie, a Reform member for York in the Legislative Assembly and publisher of The Colonial Advocate, they had previously showed themselves to be arbitrary in withholding permission.

Mackenzie had recently returned to York after spending a year in England lobbying for political change in Upper Canada and witnessing the passage of the Great Reform Bill of 1832. In England he had been familiar with leading reformers like Joseph Hume and reform organizations such as the Birmingham Political Union. He had opposed the building of the new market, convinced the cost of food in York would be higher because the magistrates intended to retire the building loan from market rents and fees rather than from the general revenues of the district. In August, 1831, just before construction began, he had appealed to Sir John Colborne, the Lieutenant Governor, to annul the York Market Bill and derail the project, but Colborne turned a deaf ear. Subsequently, the Legislature passed the City of Toronto Act on 6 March 1834, vesting title to the Town Hall and market in the municipality and making it, not the tenants and their customers, responsible for the construction debt.

In the city elections which followed on 27 March, Mackenzie triumphed over the Tory magistrates and majority in the legislature who supported incorporating the City of Toronto as a means of spinning off the large loan. Not only was he elected to Council, but more was to come. To the dismay and anger of the tories, when the ten councillors and ten aldermen met in the Town Hall, henceforth to be known as the first City Hall, to elect the first Mayor from among their number, Mackenzie was chosen to take the chair by the narrowest of margins. When the Mayor and the Common Councillors, except for the tory members, went to pay their respects to the Lieutenant Governor, he received them coldly and did not invite them to be seated. After brief expressions of formal co-operation, the audience was concluded within two or three minutes.

One of the first problems the new Council faced was where the city offices would be accommodated. It was solved at the beginning of March, 1834, when Henry Mosley vacated his auction room and granary in the City Hall’s west wing. The corporation intended to occupy this space on a temporary basis as offices for the Mayor, Clerk of Council, Chamberlain and Police until more permanent arrangements could be made. An inquiry was made without success to see if the district magistrates could make rooms available in the Court House for the Police Office and Mayor’s Court. Other quarters may have been investigated too, but the longer the offices remained in Mosley’s former premises, the more obvious it was that they would remain there. These half dozen rooms and a housekeeper’s apartment were the principal city offices for Toronto’s first decade.

There was little doubt that the City Hall would continue to serve as the Council chamber while being used for a variety of other activities. In the summer of 1834, a railing was built across the room to divide the main part from the area where council convened. A handsome Mayor’s chair was ordered from James Myers; eight benches provided seating for the public. Council met around a cloth-covered table, dealing with such matters as a petition from the butchers presented in April 1834. It complained about competition from people selling meat outside the market and forestallers who appeared in the square before noon to offer cuts of meat at lower prices than the butchers. Council responded by passing stricter market regulations.

Besides marketing, the square was the setting for many other events. During a three-month period in 1834, the annual May Fair of the Agricultural Society including a show and sale of livestock took place; Ellen Halfpenny was confined to stocks in the marketplace for interrupting the Mayor’s Court during her third appearance there in almost as many weeks; and a ‘Grand Meeting’ of citizens was convened by Mackenzie to consider the levying and assessment of city taxes and what might be done to relieve destitute emigrants. The Advocate reported about 2000 persons were present at the meeting on 29 July 1834, although others estimated the attendance was smaller. After Mackenzie spoke he was assaulted by a woman, thought by the Patriot to have been the hapless Halfpenny, who seized and shook him. The meeting broke up shortly after to jeers and catcalls as the rival Tory and reform supporters tried to drown out each other.

Mackenzie was escorted home by his supporters, and was not present the next day when the meeting was reconvened. Tempers were short and a fight broke out. To avoid becoming involved, between forty and sixty people surged up one of the stairs to the gallery which gave way under their weight. Three were killed, lacerated by meathooks in the stalls below. One of them was the sixteen-year old son of Captain James Fitzgibbon, the hero of the Battle of Beaver Dams in 1813.

Tenants for most of the butchers’ stalls had been found readily when they were auctioned in December 1832, but it took longer to rent the granaries. Advertisements suggested they would make excellent places to exhibit dry goods. “A Market Gardener and dealer in flowers, fruits, shrubs, trees, etc., would find one or two of these apartments, with the use of the Gallery adjoining, extremely suitable.” In the early years, however, it was the printing trades and public bodies which seemed to find the granaries suited their needs best. Samuel Oliver Tazewell, the first lithographer in Upper Canada, had his shop there in 1834-36, and at least five of the city’s newspapers — The Advocate, Albion of Upper Canada, Canadian Correspondent, Courier of Upper Canada and Toronto Recorder and General Mercantile Advertiser — were printed in different granaries.

The longest tenancy in the market buildings was that of the Commercial News Room, which from 1834 to 1847 provided its members with a selection of newspapers and periodicals upstairs in the east wing overlooking King Street. The briefest was probably a theatrical offering, “The Burning of Moscow,” which was exhibited in one of the granaries for a few evenings until Council was threatened with suspension of its fire insurance policy. During the 1830s, the Mechanics’ Institute and organizations like the reformist Canadian Alliance Society were tenants in the granaries as were religious bodies such as the Irvingites. In 1836 the wardens of the Roman Catholic Church leased a granary for a schoolroom. Had council responded favourably to a 1837 petition by Charles Fothergill, a Lyceum of Natural History and the Fine Arts would have been established in two other rooms.

Ill. 4: In 1844/45 the artist John Gillespie painted this view of King Street looking west from in front of the first City Hall, seen at the left margin. (ROM 85 Can 128, acc. 955.175)

Besides printers and public bodies, a succession of commercial firms had their stores, offices and warehouses in the market buildings. Gillespie, Jamieson & Co. and Henry Mosley were followed by others like the feed and grain business of William Gamble & Co. (which occupied the four granaries on the east side of the square in the 1840s), Gooderham & Worts, and the Consumers’ Gas Company after it was founded in 1847. At times of political unrest, some granaries were used to store arms or were put at the disposal of the special police and volunteer forces. During 1837-38 and again following a serious riot in 1841, a military guard was posted at the City Hall. Most of the time, however, the council chamber echoed to less martial activity. Typical were a concert on piano and guitar by Professor Julius von Holtz’t; a public showing of James Cane’s map of Toronto which he was intending to have engraved; and exhibitions of the Toronto Society of Arts in 1847 and 1848.

Never again in the history of Toronto perhaps would so many diverse uses be found together, and the classical ideal of the agora come so near to being realized, as in this City Hall and Market. By the 1840s, however, the buildings were no longer considered to be in keeping with Toronto’s needs or dignity. The city offices constructed as walk-up rooms and warehouses were clearly inadequate, while council found it inconvenient to share the City Hall with a full schedule of concerts, lectures and charities. Even for these latter uses the hall, described with sarcasm by the British Canadian as “that splendid Temple of the Muses,” was not particularly well-suited. As for the market, it had few admirers. A great source of complaint was the crowding caused by combining both the grain and food markets; it only got worse as the city grew. Another annoyance was the filthiness of the square. Rarely free from cabbage leaves, bones and skins, its odour was overpowering. In 1843 the Examiner reviewed the plan of the Ste. Anne’s Market in Montreal – a long building enclosing stalls on both sides of a central aisle – and recommended it as “decidedly the best in construction and convenience which is to be met with in America.”

Dissatisfaction arose as well because the buildings were out of keeping with Toronto’s architectural ambitions. In 1844 the Toronto Star suggested, “There is no city that needs a little architectural taste more than ours, for hitherto we have had a most melancholy lack of it.” Although the City Hall had come to serve as a municipal seat only by accident, it was subjected to unflattering comparisons with Kingston’s grand City Hall and Market, then approaching completion to designs by George Browne who was responsible also for Montreal’s Ste. Anne’s Market.

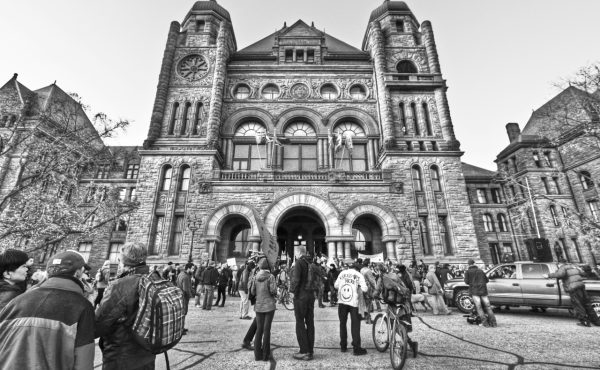

In January 1844, moved by self-interest and civic pride, Toronto Council called for plans for a new market house which would also include municipal offices. Construction of this building began in spring, 1844, on a site at Front and Jarvis Streets, immediately south of the old market. Work was well along by the following November when council again requested design proposals for “a new front to the old market buildings” to replace the old City Hall with better accommodation for the city’s cultural activities. Although a design by William Thomas was subsequently awarded the first premium, council chose not to proceed with the project, probably for reasons of cost. Thus, when the City moved into its new quarters in early fall, 1845, the old City Hall continued to serve for public assemblies and entertainments until it was destroyed by the Great Fire of 7 April 1849.

The fire began east of Jarvis Street in an area of mostly wooden buildings. It spread quickly, fanned by the wind which carried embers westward across Jarvis Street. Stores along the north side of King Street soon were blazing. Not long after, St James’ Cathedral was ignited. Then the fire jumped to the south side of the street and took hold in the old City Hall, which was destroyed with its wings along King Street. Luckily, the flames were stopped from spreading to the adjoining market buildings or they would have been lost too.

After architects John Howard and Frederic Cumberland had made independent estimates of the damage, the city’s claim with the British America Fire and Life Assurance company was settled for £1,252. For a brief time consideration was given to rebuilding as before. By early June 1849, however, opinion had swung in favour of demolishing the ruins so the long-approved plan by William Thomas for a new front to the old market buildings could be realized. Toronto’s First City Hall disappeared that summer to make way for Thomas’s St Lawrence Hall. The market was left standing and continued to operate until the Spring, 1850, when it was demolished for a new market arcade extending between St. Lawrence Hall and Front Street.

Ill. 5: In the late 1880s the Rev. Henry Scadding, then an old man, made this sketch of the first City Hall and market from memory. In spite of its inaccuracies it is still used frequently to illustrate the buildings. (TPL, B-1-27b, T 11556)

Thus ended the short life of Toronto’s first City Hall which was also the first municipal seat in the province. It received so little attention while standing that by 1856, less than seven years after it was demolished, substantial inaccuracies could be found in the Globe’s recollection of the building and its history. Others like the Rev. Henry Scadding unintentionally added to this misrepresentation. For understandable reasons, it has been obscured by the brilliant history of St. Lawrence Hall on the same site and the nearby second City Hall, a portion of which survives as the City of Toronto Market Gallery. But while the first City Hall has been all but forgotten, its original purpose is clearly recalled in the use to which its successors, St. Lawrence Hall and second City Hall, have been put.

Stephen Otto is a local historian and the former chair of the Friends of Fort York. The author of this post wishes to thank Christopher Moore, Ramsay Derry and Michele Dale for their help in putting it together.