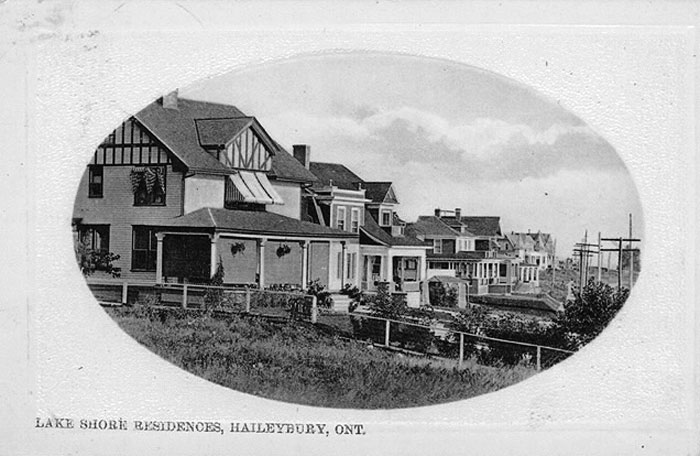

The town of Haileybury sits on the shore of Lake Timiskaming, a serpentine body of water on the northern reaches of the Ottawa River that marks the border between Ontario and Quebec. From the town’s little main street, it’s almost two hours drive south to North Bay, and another hour to Sudbury.

Today, Haileybury is a picturesque if unremarkable community that amalgamated with the nearby towns of New Liskeard and Dymond to make Temiskaming Shores in 2004. But in 1922, the entire town of several thousand people was reduced to rubble and ashes—burned to the ground by a ferocious wildfire that still ranks among Canada’s most severe natural disasters.

“It is the worst disaster that has yet overtaken Northern Ontario,” Globe reporter Frank Phillips told a stunned province on October 6, 1922.

“Outstanding is the destruction of Haileybury. Where the county town of Timiskaming stood looking over the blue shores of the lake—a community of fine homes and splendid public buildings—there is now nothing but a waste of charred ruins.”

Whipped by 96 km/h winds, the fire blasted through the town in the early afternoon. Around 3:30 p.m., a general alarm was raised when the flames leapt across the town’s rail tracks. Within minutes, the entire business section of the city and the cathedral were alight.

All of Haileybury’s roughly 3,000 inhabitants poured into the streets, desperate to flee. Most gathered along the wharf in the hope of catching a boat or sheltering by the water. In nearby Cobalt, people gathered at the station in the hope of catching a train out before their town was likewise incinerated.

Reporter Phillips related the unfolding disaster in frantic detail by telegraph to the Globe office in Toronto. “Wild rumours are flying, and the smoke is so thick that one cannot see,” he wrote.

“All Haileybury is gone except a handful of houses … the hospital, cathedral, schools, and hotels are wiped out, and the entire business section is nothing but bare ground,” he reported at 10:55 p.m. “The number of fatalities in the destruction can only be guessed, but your correspondent saw half a dozen people fall in the flames or dead by the roadside.”

“In fifteen minutes after the fire jumped the railway track thousands of buildings were ablaze.”

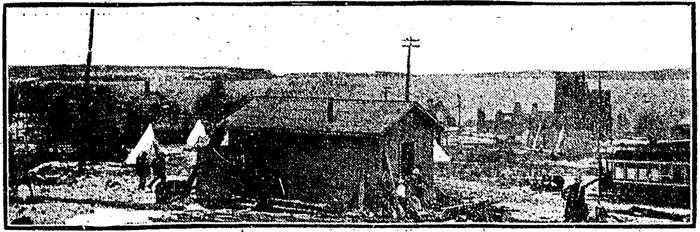

The full-scale of the death and devastation became clear when dawn broke on the morning of October 7. Haileybury was completely destroyed and practically all of its inhabitants homeless. Bodies lay in the smouldering remains of buildings and lost children wandered the streets seeking their parents.

Those who were able caught a refugee train headed to North Bay. “‘Mammy, I want to go home,'” Phillips recalled hearing a child tell its mother as they boarded the train. “‘God bless you, my child, you’ve got no home to go to,'” came the response.

The timing of the fire was particularly unfortunate. The first snow of the season was expected in the coming weeks and temperatures were forecast to fall dramatically.

The Timothy Eaton Co. dispatched a railway car to the town packed with clothes, overcoats, and shoes for adults, children and babies. The store also included packages of bacon, potatoes, vegetables, tinned meats, flour, sugar, and coffee that were handed out at the mayor’s home, which was one of the few to escape serious damage.

The Salvation Army sent 500 overcoats and other items of clothing to the town, the Red Cross set up a station there, but the primary concern was the lack of shelter. Even basic wooden huts wouldn’t be ready before the weather worsened, and the threat of additional deaths due to exposure was real.

Surprisingly, a partial solution to the crisis was to be found on the streets of Toronto.

In 1921, many months before the fire engulfed Haileybury, the newly-formed Toronto Transportation Commission had suddenly found itself with a surplus of streetcars. At its formation, the city-run TTC took over the operations of the private Toronto Railway Company and the public Toronto Civic Railways organization.

In addition to merging the separate entities together and taking on their equipment, the TTC also elected to purchase a fleet of more than 500 new streetcars. The oldest, most decrepit vehicles from the predecessor organizations would be scrapped.

Fortunately, the disaster in Haileybury occurred before the TTC could send its surplus streetcars to the scrapheap.

Toronto formally offered to ship the streetcars to Northern Ontario as temporary shelters on October 8, 1922, but the offer was politely declined by officials in North Bay. “Evidently the people of the north had heard too much about Toronto’s street cars to wish them even as emergency homes,” the Star wrote.

Despite their ramshackle appearance, the disused streetcars were actually remarkably well-suited to housing the displaced populace. Firstly, and perhaps mostly importantly, each was weatherproof with doors and windows. Best of all, many had built-in coal stoves—leftovers from a time before electric heaters.

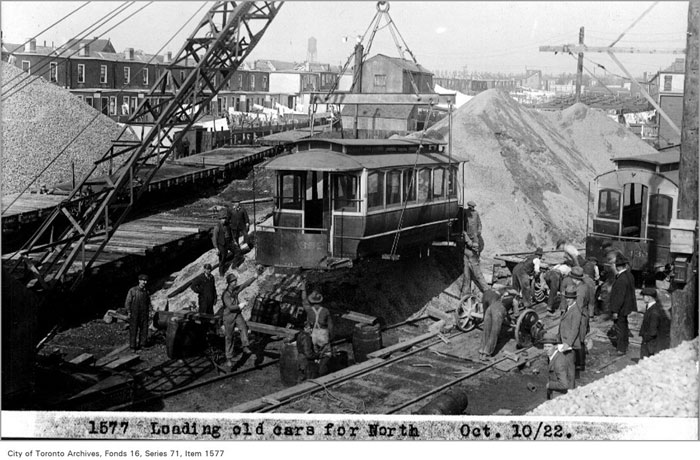

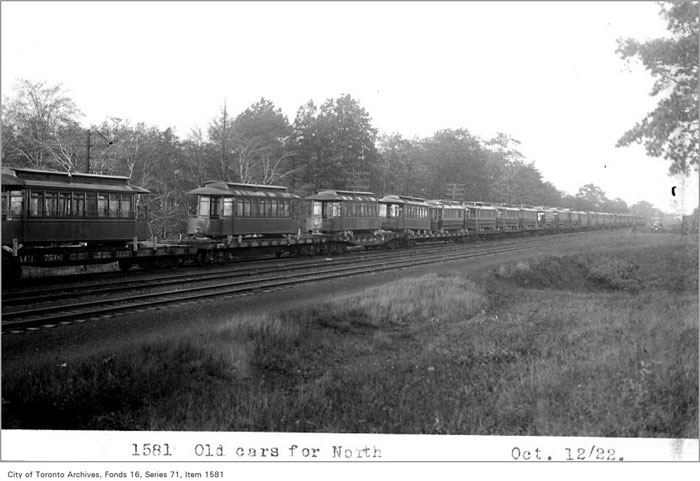

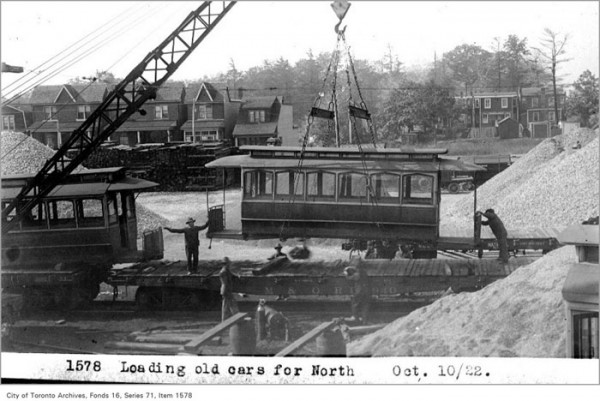

Toronto’s offer was reconsidered, and word arrived on October 10 that Haileybury would indeed accept the shelters. Starting at 7:00 a.m. on October 11, 87 disused TTC streetcars were stripped and loaded on the back of Canadian Pacific flatcars at a facility on Coxwell Avenue.

The first of the bunch were handed to displaced families on October 17, according to the Star. 60 stayed in the hardest-hit town of Haileybury, but others went to the towns of North Cobalt, Charlton, Thornloe, and Heaslip.

“In my street car I am going to put in another floor to make it a little warmer. Then we will make the beds at one end, have the kitchen in the centre by the stove and have a living room and parlour at the other end,” an unnamed man was quoted as saying by the Star. “My wife is all tickled with the idea of our new streetcar.”

“We will be as cosy in them as bugs in a rug, even if it does get forty degrees below zero,” said another.

Those who were unable to secure a coveted TTC streetcar—and there were many—were given free lumber to build a shelter. By the time the men in Haileybury had begun to unload the town’s new shelters, a thin layer of snow was already on the ground.

As Haileybury and its neighbours began to rebuild, local officials quickly launched a formal inquiry into cause of the fire. Despite calls to suspend the investigation until the population could be guaranteed safe shelter, the probe pushed onward, eyeing with suspicion farmers seen burning garbage or potato stalks in the days before the disaster.

It quickly became clear, however, that several wildfires had been burning unchecked around Haileybury for several days before the town was incinerated. High winds ikely fanned the flames, blowing it directly in the direction of the unsuspecting towns.

An estimated 43 people were killed in the Great Fire of 1922 and an area of 1,200 square kilometres of land was reduced to ash. Just a few buildings remained untouched in Haileybury, where losses were calculated to be in the region of $8 million.

Most of the Toronto streetcars were replaced or scrapped in the decades following the fire. One, however, remained in use as a farm shed into the 1990s.

It was lovingly restored and is now on display at the Haileybury Heritage Museum.

4 comments

My grandparents survived the Haileybury fire — an oft told story in my family. She under a blanket in the middle of a field. He, in the river with the cattle.

My mother, who was living in North Cobalt, survived as a small child by standing in the lake (in Oct). She remembered the Red Cross bringing in supplies. All her life was haunted by wall of fire dreams.

My family moved into our home on Lakeshore Road in Haileybury in the early 1950’s, and my parents lived there until 1991. The fire stopped half a block before this house (at Probyn St), so it survived. Apparently it was owned by a(the?) pharmacist, so he set up shop in the front porch. When we moved in, in the back porch we found pieces of cardboard with bottles of aspirin attached, and a few other remnants of that “store”. Unfortunately, it was all thrown away… It was interesting to me that all the “big” Lakeshore Road homes did not burn, but the rest of the town did… There must have been some “discussion” about this.

My great grandparents George and Lillian Rochester survived the fire. George had a hardware business with Sam Norfolk and a mine operation and was involved with the Temiskaming Navigation Company. During the fire Lillian with other women stood in the lake while the men heroically worked to help others. As a youngster, I often heard accounts of the devastation from my great-grandmother. George died in 1925 and Lillian in 1954. As a 7 year-old I remember travelling on the train from Toronto to Haileybury with the coffin in the baggage car for the funeral. We stayed at the Haileybury Hotel and the first morning I had gotten up very early and went downstairs alone, ending up in the kitchen where the chef made me a breakfast. My frantic father showed up later after having searched for me everywhere. I remember him even sitting down in the kitchen to a plate of eggs and toast. Oddly, I don’t remember the funeral.