Toronto Water’s ongoing efforts to complete a state-of-good-repair overhaul on the St. Clair Reservoir, under Sir Winston Churchill Park, could be described as both monumental and mundane.

Monumental, because the facility normally contains 220 million litres of fresh drinking water that is pumped up Russell Hill and accounts for fully 10% of the entire city’s storage capacity. (It provides supply and pressure to a part of the city that extends from Dupont south to College, and from west end Toronto to East York.)

Mundane, because the $25 million project, due to be finished in the summer of 2019, involves mostly routine engineering tasks, such as repairing cracks, replacing or fixing valves and managing all the topsoil on the reservoir’s roof.

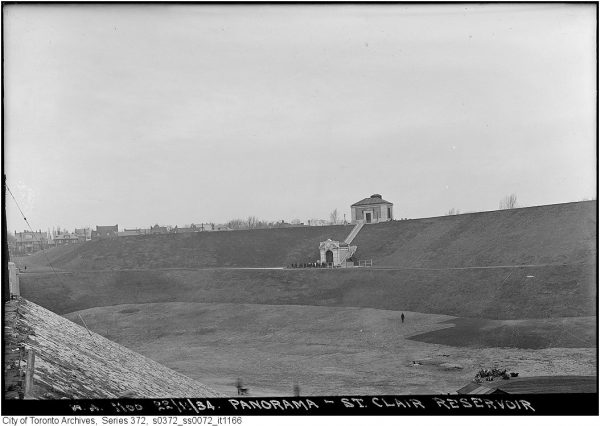

But for the civil engineers tasked with completing the job, one particular detail stands out: the facility, which bears the city-building imprimatur of Toronto’s long-time works commissioner R.C. Harris, has been in service continually since it opened in 1931. This project, amazingly, marks the first time it’s been taken off line for repairs.

As Mike Brannon, Toronto Water’s manager of supply, put it during a tour of the construction site he gave to Spacing earlier this fall, “The concrete is in relatively good shape for 85 years.” Indeed, it would be difficult to identify many other pieces of public infrastructure that have functioned for so long without a trip to the shop for repairs.

Earlier this fall, Brannon and two engineers involved in St. Clair Reservoir project gave Spacing a tour of the construction site and a bit of a history of a civic works project that has played a largely unsung role in Toronto’s evolution.

“This site,” Brannon explained, “was really important for Harris.” In the late 1920s, as is well known, he was pushing to secure city council approval for a plan to build the new east end water filtration plant that would later bear his name (construction eventually began in 1932). But Harris, during his temporary stint as the head of the newly-established Toronto Transit Commission, had also played a key role in the development of the St. Clair streetcar line, and regarded that east-west thoroughfare as a venue for creating an integrated network of public spaces.

The St Clair reservoir, Brannon explained, was part of a larger set of projects that included the Spadina Road Bridge across the Nordheimer Ravine, and a green boulevard along St. Clair Avenue West. It mirrored the open-air Rosehill Reservoir, which dated to the 1870s, and was part of a broader effort to encourage the city’s northward development.

The site itself included a landscaped park on top, punctuated by the limestone and yellow brick head houses designed by Thomas Pomphrey, the architect of the water filtration plan. As part of the current project, Toronto Water’s heritage subcontractor, Clifford Restoration, will clean and re-point the brick on those structures, install a new copper roof and replace worn elements like finials, cornices and terrazzo flooring. “We’re keeping it true to the original state,” said Brannon, who pointed out that the project team closely studied original blue prints and archival images as part of their preparation.

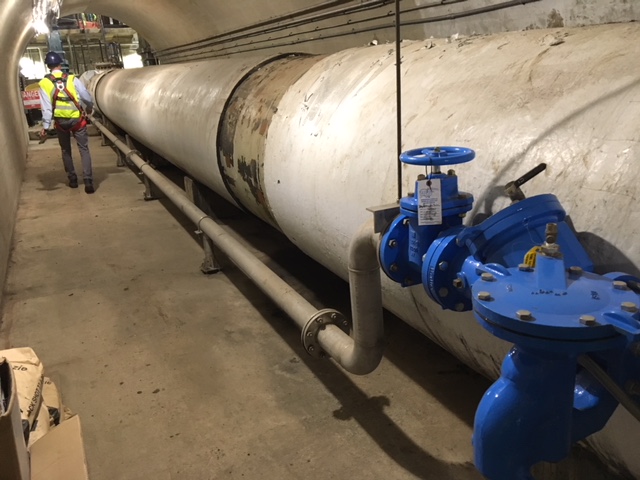

Inside, the bulk of the work involves replacing the external water-proofing membrane, repairing old 48-inch valves on the large pipe leading into the reservoir and then undertaking all the routine maintenance work on the interior.

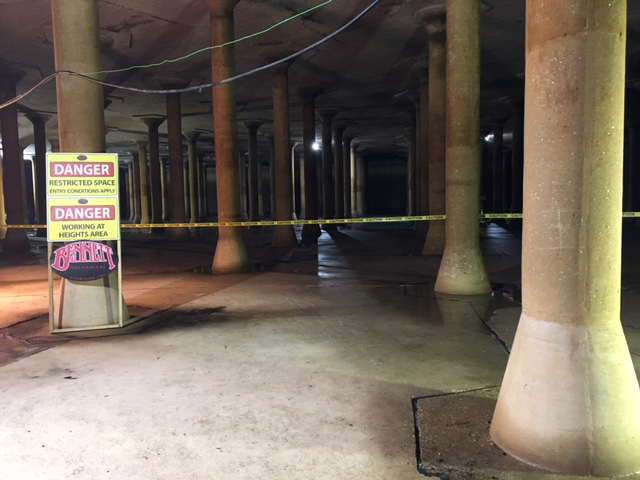

By design, the reservoir itself is divided into two self-contained tanks, for redundancy and to allow maintenance to occur without taking the entire facility off line. The eight-metre high roof is held aloft by 830 columns, each of which sits on eight-inch concrete slabs. The dim interior has the look of a vast, ghostly temple.

The floor is sloped slightly towards a drain that is covered with a platform meant to prevent vortexes and the problem of air bubbles forming in the fresh water pipe network fed by the reservoir. According to Brannon, the reservoir contains 17.1 km of internal and external expansion joints, all of which are being replaced.

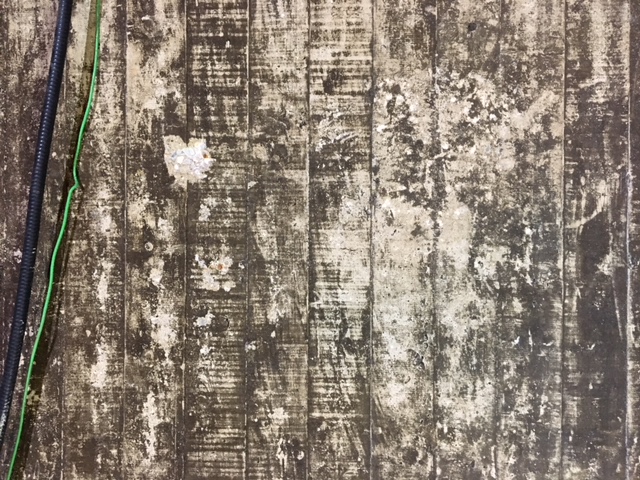

All of it, of course, was built with techniques from the late 1920s – plumb and bob surveying tools, and the use of burlap sacks applied to the freshly poured concrete to assist in the curing process (see photo below). “Compared to other concrete structures of that age, the walls and columns are in great shape,” said Ken Koson, a senior City of Toronto project manager.

Once all the work is complete, Brannon said, the tanks are subject to an intensive cleaning and decontamination process prescribed by the Ministry of the Environment. The procedure begins with an extensive spray down with chlorine wash followed by further disinfectants and a week of monitoring and testing.

It’s worth noting that the City officials involved in this project have been clearly mindful of the reservoir’s rich history. The site scaffolding has been decorated with a series of archival photographs depicting the original building process. They told me they have also been inspired by the durability of construction and workmanship that was overseen by R.C. Harris almost 90 years ago.

How long will this set of repairs last? “Another hundred years,” said Koson. “Ultimately, you want to make this thing last indefinitely.”

top photo by Eric Parker; bottom photo from Toronto Archives; all other photos by John Lorinc