In 1841, travelling American circuses came to Toronto for the first time and blackface came with them. According to University of Toronto theatre professor Stephen Johnson and historian Karolyn Smardz Frost, members of Toronto’s black community petitioned City Council annually until 1843 to prohibit these acts. But every year Council rejected their pleas to censor these blackface actors and racist depictions, among them Jim Crow ‘at home’ on the plantation.

This version of Toronto and City Council may seem impossibly distant, but every Halloween season reminds us that blackface incidents are actually not behind us — a message reinforced last week when NBC morning host Megyn Kelly could not understand why it was inappropriate for white people to wear blackface for Halloween.

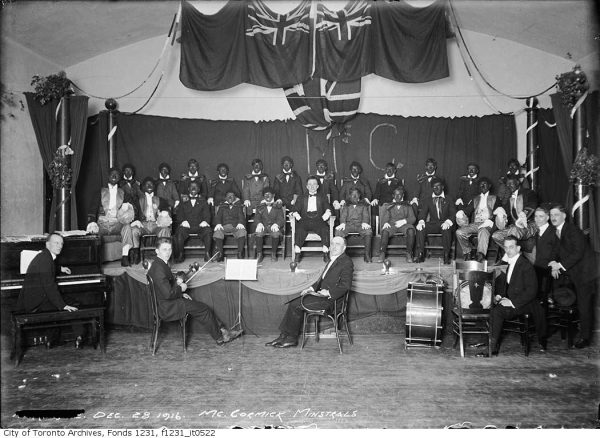

While doing PhD archival research on Canada’s black beauty culture at McGill University, and Canada’s history of blackface as a Banting Postdoctoral Fellow (2016-2018) at the University of Toronto, I consistently stumbled upon ads and/or editorials about blackface spanning the 1860s to 1950s. I also learned that blackface existed outside traditional theatre, at athletic clubs, rotary clubs, high schools, summer camps, public parks, private businesses, and even churches.

This five-year research led me to conclude that there is no simple answer as to why blackface persists today. But what makes Canadian blackface unique is that, unlike in the U.S., it is rarely framed as a ‘Canadian’ pastime but instead is isolated to a few students and/or teachers making ‘innocent’ mistakes.

In 2009, when a group of white University of Toronto students put on blackface makeup that mimicked the Jamaican bobsled team during a Halloween party, detractors were cast as ‘overreacting’ to an apparent attempt to pay homage to the movie Cool Runnings, based on the Jamaican national bobsled team’s debut at the 1988 Winter Olympics in Calgary. A couple years later, a similar blackface ‘homage’ to Jamaica at the University of Montreal landed Canada on CNN. If then-McGill law student Anthony Morgan (who is Black and of Jamaican descent) had not walked past the frosh week event, posting a video to YouTube showing the white students in fake dreadlocks and darkened faces with Jamaican accents, the incident likely would have been ignored. But it also begs the question: how many events like this one never make it into the public realm at all?

From coast to coast, blackface continues to happen because there is a pervasive lack of understanding about the genre’s history – not just as an American tradition, but as a Canadian one, as well.

Historically, blackface begins as a form of performance known as “blackface minstrelsy,” which traces its origins to the theatres of New York, Boston, and Philadelphia in the 1830s and 1840s. By the 1850s, professional American and British minstrel acts (i.e. three-part shows) performed on stages in western, central, and eastern Canada.

These troops called it ‘blackface’ because the performance included a blend of popular music, dance, and comedy, all aimed at mimicking African Americans both on the southern plantation (‘Jim Crow’) and in the industrialized north (‘Zip Coon’). Performers wore what was known as “burnt-cork” facial makeup – a mixture of charred and crushed champagne corks and water or petroleum jelly. At its core, the minstrel show was about maintaining both a real and imagined line between who belonged and did not belong to the national identity.

Putting on blackface, according to William Mahar, author of Behind the Burnt Cork Mask: Early Blackface Minstrelsy and Antebellum American Popular Culture (1999), allowed professional and amateur white entertainers to shield themselves from any direct personal and psychological identification with the material they were performing. Black people were thus disembodied and dis-identified from these moments of national storytelling, although, paradoxically, they became the basis for a distinctly American brand of entertainment. It is the reason why, since the 19th century, popular culture has been synonymous with African American culture, i.e., jazz to blues to hip-hop.

In Toronto, when the Royal Lyceum, the city’s first purpose-built theatre, opened in September, 1849, it became the primary venue for the performance of blackface minstrelsy. Located behind a row of buildings on the south side of Adelaide Street West between Bay and York Streets, the Royal Lyceum burnt down in 1874. By then, the new Grand Opera House, located at 9-15 Adelaide Street West, near Yonge Street, and the Royal Opera House, became the theatres of record for professional blackface in the city.

At the turn of the twentieth century, Toronto established itself as one of the leading stops on the American circuits because its audiences preferred American entertainers, minstrel shows and actors over British troops. Audiences for these shows comprised the city’s Anglo elite, whose members sat on the same boards, attended the same schools and worshipped in the same churches. Hence, blackface in Toronto, from the latter part of the 19th century through to the 1950s, was the domain of an Anglo cultural (but not necessarily economic) elite class.

For ethnic immigrant whites, ‘blacking up’ and then ‘wiping off’ the burnt cork mask performed a different function. It enabled them to move from immigrant ‘other’ to full citizen. Stated otherwise, by mimicking African Americans, ethnic immigrants could assimilate into the broader culture while simultaneously removing their ‘otherness’ at the same time. If the dominant culture viewed Black people as the target for jokes and ridicule, newly arrived immigrants, whether they held such beliefs or not, followed suit.

Al Jolson, born Asa Yoelson, is the perfect example of this phenomenon. In The Jazz Singer (1926), for instance, Michael Rogin, the late-Robson Professor of Political Science at the University of California, Berkeley explains that when Jakie Rabinowitz becomes Jack Robin in blackface singing ‘My Mammy’ to his immigrant Jewish mother, it provided America proof that in the period of mass European immigration, its melting-pot culture was accessible to everyone. Except African Americans, that is.

Similarly, in Montreal, which has an historical Jewish community that parallels that of New York, the Montreal’s Jewish Public Library archives contain an extensive collection of photos and playbills from blackface minstrel shows put on by the Young Men’s Hebrew Association (YMHA). Blackface, in other words, is as fundamental to North American culture as immigration, popular culture and race/ethnicity.

Sure, blackface is about racism. But it also speaks to ‘something else’ — a collective amnesia about the lived experiences of Black people in Western culture, and to the tensions between belonging to and alienation from, the nation. Whether intended or not, blackface was — and still is — used strategically in public and private clubs, institutions, and theatres to exclude Black people from full participation. Trevor Noah’s “Use Leo Deblin’s ‘Ask-A-Black’ Service” on the Daily Show, while a joke, speaks to the lack of diversity and understanding about the Black experience in boardrooms, and in many instances, classrooms.

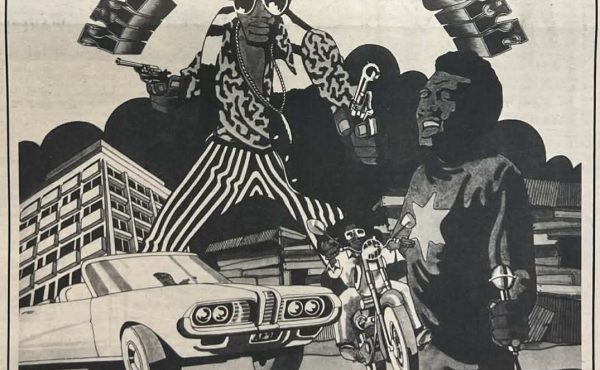

Contemporary blackface, then, is actually a misnomer. What we are witnessing on university campuses or at community events is a form of neo-minstrelsy that must be framed in terms of a racialized socio-cultural politics, not just as racist acts.

McGill critical race scholar Philip S. S. Howard, who has started researching contemporary blackface incidents on university campuses, argues that it is, in its visual form, reminiscent of historical blackface minstrelsy as a form of sartorial performance. But, he writes, contemporary blackface also “draws upon the ways that blackness is conceived on in dominant Canadian discourse today – most notably as foreign.” Hence, the ‘Jamaicanization’ of blackness in the contemporary context, Howard argues, reveals the ways in which blackness is now framed in Canada.

While I agree with him, we still need to contend with the obvious question: why has blackface never gone away? Every time I mention my work to someone over the age of 50, they recount a story about themselves or a family member taking part in a blackface performance as a youth, not stories of their children’s contemporary blackface performances.

In other words, contemporary blackface is really a continuation of a centuries-long practice of domination over Black people that requires us to think beyond race. Instead, whenever the next blackface incident occurs – and given that Halloween is approaching, it could be very soon – the conversation needs to move toward an understanding of the entanglements of racism, classism, and white supremacy today, as well as blackface’s origins over 180 years ago.

Bashir Mohamed, an activist with Black Lives Matter in Edmonton, has been tweeting historical images of blackface in Alberta, an act that connects the past with the present. The more we do this, the sooner we will begin to unify the two competing narratives of belonging/exclusion that explain why blackface continues.

photos courtesy of the Toronto Archives

Cheryl Thompson is an Assistant Professor in the School of Creative Industries, Ryerson University. She is currently writing her second book, Uncle: Race, Nostalgia and the Cultural Politics of Branding, which will be published by Coach House Books in 2020. Follow her on Twitter at @DrCherylT