As the City celebrates the centennial of Toronto’s most recognizable pieces of infrastructure with the unveiling of a historical plaque, Spacing looks back at the anti-climatic opening day of the Prince Edward Viaduct — most commonly referred to as the Bloor Street Viaduct — and what the bridge could look like in the future.

The day the Bloor Viaduct opened up Toronto’s east end

Although the approval, design and construction had dragged on for almost a decade, with one early proposal spiked during a referendum by cost-averse voters, the opening of the Prince Edward Viaduct was decidedly anticlimactic, especially compared to the magnitude of the mythology that emerged afterwards.

With the Armistice less than a month away, the city was in the throes of the Toronto version of the worldwide Spanish Flu outbreak, and the newspapers were filled with stories about health officials seeking to limit large gatherings. According to the Toronto Daily Star, Dr. Charles Hastings, the city’s crusading medical officer of health, had ordered the closing of dance halls, theatres, and pool halls, while some churches were voluntarily curtailing services to limit potential contagion.

Given all that, the official opening of the viaduct ended up being a rather low-key affair on a cool and windy day. Mayor Tommy Church led a procession of cars across a bridge that, The Globe noted, “has been the hope of the east end of the city for many years.” But, as the reporter covering the formalities noted, the engineer overseeing the project wasn’t present because of the flu, and the other dignitaries — including Works Commission R.C. Harris, who had overseen the $2.5 million project — made short, perfunctory speeches to a small group of City controllers, alderman, and citizen representatives.

While the initial proposal to bridge the Don Valley further north than the existing bridge at Dundas predated Harris’ assumption of the post of Works Commissioner, he seized on the project when he took office in 1912, guiding the massive undertaking through a controversial design process that saw significant disputes over the configuration and footprint of the proposed span. One design called for a straight-shot bridge extending from Parliament to the east side of the valley, while another involved the two-stage, dog-leg span that would eventually be constructed.

During the design phase, contractors lobbied council to get Harris to build a heavier concrete structure. But he held his ground and backed a lighter design featuring three graceful steel arches, architecture that evoked his Crawford Street bridge across Garrison Creek and the later Vale of Avoca bridge on St. Clair east of Yonge Street. Harris also ordered contractors to fit out the viaduct with a second deck engineered to support an eventual subway. Almost a decade earlier, the City had commissioned studies on the feasibility of a subway system, including a line from Keele to Broadview. Voters backed the plan in a 1910 plebiscite, but rejected the cost in 1912. Harris, though skeptical about the viability of subways, nonetheless ordered the rail deck built; it went unused until 1966.

Much later, author Michael Ondaatje added to the Viaduct’s mythology by situating it as a kind of mute but overpowering character in his 1986 novel In the Skin of a Lion. Yet the true legacy of that opening day can be found on the Goad’s fire insurance maps. The 1913 version shows sparse development on the streets east of the Don Valley around Danforth Avenue. The 1924 atlas, by contrast, depicts an area that developed rapidly after the bridge opened. Previously empty lots are now filled with new stores and houses, and entire subdivisions featuring block after block of new brick homes and schools have appeared north of what is now Browning Avenue and further east along the Danforth.

It was, in many ways, the day that opened up Toronto’s east end.

by John Lorinc

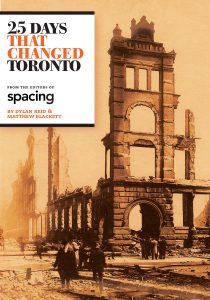

This piece is excerpted from Spacing’s book 25 Days That Changed Toronto.

Could Toronto get its own living bridge?

Toronto is no stranger to grandiose ideas. The city is also familiar with those same inspirational plans being watered down or completely dismissed. But rarely is a big idea built atop of another big idea, like the one proposed by architect Tye Farrow.

Farrow and his team envision transforming the Bloor viaduct (officially known as the Prince Edward Viaduct) into a multi-use piece of infrastructure. The iconic bridge over the Don Valley currently serves only one purpose: to move people back and forth. But Farrow believes that Toronto can learn a few lessons from many European cities in which a bridge provides many functions, such as retail, housing, and green space. Farrow’s proposal calls for parts of the viaduct to include a hotel, affordable housing, and restaurants, with a top deck acting as a linear park.

Farrow sat down with Spacing’s editor Matthew Blackett to discuss the idea.

Where did the inspiration for this project come from? Venice and Florence are cited as examples, but why did you think of the Bloor viaduct for this kind of project?

The idea came from connecting the dots with what we read in the press daily. There is a vast need for affordable housing on shovel-ready sites that are close to transit. This is especially true for the many people who come to Toronto to study (we’ve become a destination because of Brexit and Trump uncertainties). But even with university degrees, housing affordability is beginning to be a barrier to retaining these minds who will help the city flourish.

The other motivation is a new, amazing, structural material we are helping to develop that has evolved out of the automobile industry, called Grip MetalTM: a massively strong and light material that will transform the construction industry, the same way Tesla is doing to the car industry.

We see Toronto as ‘San Francisco upside down’: a city of vibrant healthy neighbourhoods separated by ravines, tenuously connected by single-use, car-oriented bridges.

The best example is the Bloor viaduct, a heroic, historic engineering feat that connects some of the most expensive real estate in the city with the Danforth Greek Town community. However, ten years ago, the City added a suicide barrier to the bridge because the location was a magnet for suicide jumpers, in the same way that the Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco attracts potential jumpers.

The added suicide barrier was a great answer to the wrong question: a pathogenic answer, not a salutogenic answer to the problem. How can we create healthy, vibrant, socially connected communities, versus creating barriers? What is most disheartening is that suicide numbers haven’t been reduced since the barrier was installed; people have moved to other locations.

The viaduct is now “fenced in,” but originally had some of the most wonderful and unobstructed views of the river valley and the downtown skyline.

You mentioned Grip MetalTM; can a bridge like the viaduct take the weight of materials needed to build it?

Our living bridge design is an arch shaped structure which rests on the massive historic concrete viaduct piers, thereby avoiding putting any load on the historic steel deck spanning between the concrete piers.

The material of our structure is made up of a natural wood equivalent to carbon fibre, mechanically bonded to metal in plywood-like layers by a metal hook velcro-like system. It will change the way that we build high quality condos, hotels, and most importantly affordable housing.

The viaduct is recognized and protected as a significant piece of the city’s architectural heritage. How do you reconcile the need to protect and preserve that heritage while at the same time modernizing its form and function?

Edmund Burke’s three-hinge concrete-steel arch bridge is a heroic, man-made feat of engineering. While beloved today, it almost was not built, as residents voted against its construction in referendums every year from 1910 to 1913.

Our design is intentionally light and effervescent — the equivalent in built terms of a dogwood tree in blossom, with white flowers in spring — bending, arching, natural in shape and form, like the valley that surrounds it. The design intentionally allows the viaduct to retain its muscularity.

One thing many of us in the Spacing office thought of when we saw the renderings was: those will be some highly sought-after condos! But one of the stated goals of the project is to provide social housing. Is the hope that commercial aspects of the living bridge, and not the real estate, is what helps to fund the maintenance and upkeep?

We have received many responses from a local and global audience as to how they can secure one of the suites, so your question is very pertinent. The city could sell the long-term air rights to the viaduct to a luxury condo developer or seven-star hotel — from whom we have received inquiries.

We believe this is a Toronto city building project that can add to the “ballet” of the city, with a mix of permanent affordable housing options for residents, shorter-term hotel visitors to the city, social incubators, restaurants, market, retail opportunities, and gathering places. The Living Bridge needs to be infused with social, economic, and cultural value.

What likelihood do you see this happening in Toronto? The decision-makers at city hall are rather risk-averse to these ideas unless someone else is going to fund it.

To be clear, we intend to bring the Living bridge to life on the Bloor viaduct.

Will it be built in Toronto first? That, I am not sure. Groups are actively approaching us on the idea of reimagining infrastructure in other cities, creating value out of something that is a liability, in cities that have less available land and higher land values.

As for the decisions made at city hall, interestingly, I have had very positive encouragement from both staff in the planning department and city councillors. Practically, they understand the value of turning a maintenance liability into a revenue generating asset, paired with creating a new healthy, vibrant community out of thin air.

This piece originally appeared in Spacing‘s Fall 2017 issue.