At this year’s Academy Awards, Hair Love won the Oscar for Best Animated Short Film. The six-minute film tells the story of an African American father learning to do his daughter’s hair for the first time. When Hair Love’s director Matthew A. Cherry walked the red carpet with Deandre Arnold, the Texas high school student who was told he couldn’t attend graduation unless he cut his dreadlocks, it reinforced how movies can shift the way we see the world.

The moment reminded me of my own hair journey. When I was 14 years old, I chemically straightened my hair with a product known as a “relaxer.” For the initial treatment, I went to a hairdresser at Markham and Painted Post roads, in Scarborough. But after a few years, I started using a home kit that also required shampoos, oils, and other accessories. This practice, repeated every six to eight weeks, led me to Mascoll Beauty Supply, then located in a shopping plaza on the east side of Kennedy Road at Wickware Drive, just north of Lawrence Avenue East.

Founded by Beverly Mascoll, this business wasn’t just a beauty products store. Every time I walked into the Kennedy Road location, other Black women who knew the products would greet me and provide product reviews or tips for how to care for my hair. The store was a retailer, but it doubled as my hair therapy centre, as well as an information clearinghouse in the years before the Internet.

Founded by Beverly Mascoll, this business wasn’t just a beauty products store. Every time I walked into the Kennedy Road location, other Black women who knew the products would greet me and provide product reviews or tips for how to care for my hair. The store was a retailer, but it doubled as my hair therapy centre, as well as an information clearinghouse in the years before the Internet.

Today, Black beauty supply stores in the GTA still exist, and many of them are owned and operated by Black women. But the trail Mascoll blazed is largely unknown to many young women who frequent these shops.

Mascoll’s rags to riches tale of perserverance, strength, and a desire to give back to her community is comparable to trailblazer Madam C.J. Walker, the African American woman millionaire who, at the turn of the twentieth century, revolutionized the Black hair care industry with her “hot-comb-press-and-curl” technique. During Black History Month in Canada, we often don’t hear about Black entrepreneurs such as Mascoll, who also changed the country’s Black beauty industry in the twentieth century.

Born in Nova Scotia in 1942, Mascoll relocated to Toronto in the late 1950s. She began her career as a receptionist at Toronto Barber and Beauty Supply (still in operation today at Dundas and Bay, as well as other GTA locations). Almost immediately, she noticed that Black beauty products were few and far between. Instead of spending years complaining about this problem, she took it upon herself to do something about it.

Working out of her home in 1970, Mascoll launched Mascoll Beauty Supply Ltd. with $700 in start-up capital. At the time, there was no Black hair care product distributors in Canada. Once she established her business, Mascoll needed to partner with a major product manufacturer.

As no such company existed in Canada, she travelled to Chicago and met with George E. Johnson, whom she convinced to make her company the sole Canadian distributor of Johnson Products, the largest Black beauty company at the time, and its Ultra Sheen product line. Upon returning to Toronto, Mascoll started selling the product out of the trunk of her car until she could afford to establish retail stores. By 1971, her company was one of the leading distributors of Black beauty products in Canada.

Mascoll’s career saw her go from selling products out of her home to becoming the number one Black distributor in the country – a run of success that speaks to the cultural sentiment of opportunity and entpreneurialism that swept across Toronto during the decade. When my parents moved to Scarborough in the mid-1970s they were able to buy a house and raise four children like so many of their other Black West Indian friends who similarly were able to open businesses and/or move into the middle-class.

Black media also grew at this time. Alfred W. Hamilton and Olivia Grange-Walker launched one of the city’s first Black newspapers, Contrast, as a biweekly in 1969 and then a weekly in 1972. Arnold A. Auguste established Share (still in publication today) in 1978, as a weekly newspapaer aimed at the GTA’s Black and Caribbean communities. Both of these news organizations acknowledged that in the 1970s, Black Canada was not only here, but active in many parts of the GTA.

Like Mascoll, these trailblazers recognized a gap in the marketplace and did something to change it. Yet they also had to contend with a climate of racism and exclusion. In 1977, for example, several racially motivated acts of vandalism and violence that were commonplace in Scarborough reached the pages of the New York Times. In a feature titled, “Upsurge of Racism in Toronto,” the article reported on the surge of violence. “After the big front windows of Aslam Khan’s expensive house in the Toronto suburb of Scarborough had been shattered by stones for the fourth time, he moved his family to less conspicuous quarters in an inner‐city apartment building.”

Alfred Hamilton, interviewed by the Times, explained that “[i]nstitutionalized racism affects black Canadians as a fact of life and everyone is aware of it.” Cecil Foster, Contrast’s editor in the 1970s, wrote that the newspaper “was a magnet for all budding black journalists — and there were many of us with talents honed around the world — who found the newspaper an oasis in a bleak landscape where blacks, for the main part, were not seen as reporters, editors and certainly not as on-air presenters or actors. Hamilton and Contrast were ground zero for these struggles.”

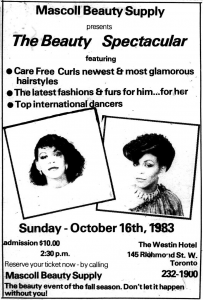

Mascoll’s Beauty Supply similarly provided spin-off opportunities for other Black entrepreneurs, hairdressers and stylists to thrive amid a beauty culture industry that virtually ignored Black women (and men). She was fearless. By the 1980s, her business expanded to include beauty demonstrations and conferences, professional hair care seminars. In 1984, she held the first ever Black beauty trade show in Canada.

Mascoll’s Beauty Supply similarly provided spin-off opportunities for other Black entrepreneurs, hairdressers and stylists to thrive amid a beauty culture industry that virtually ignored Black women (and men). She was fearless. By the 1980s, her business expanded to include beauty demonstrations and conferences, professional hair care seminars. In 1984, she held the first ever Black beauty trade show in Canada.

At its height, in the 1990s, Mascoll Beauty Supply had five locations (in addition to Scarborough, there were two downtown, one in Mississauga and one in Bramption).

This decade marked the zenith in the life of Mascoll.

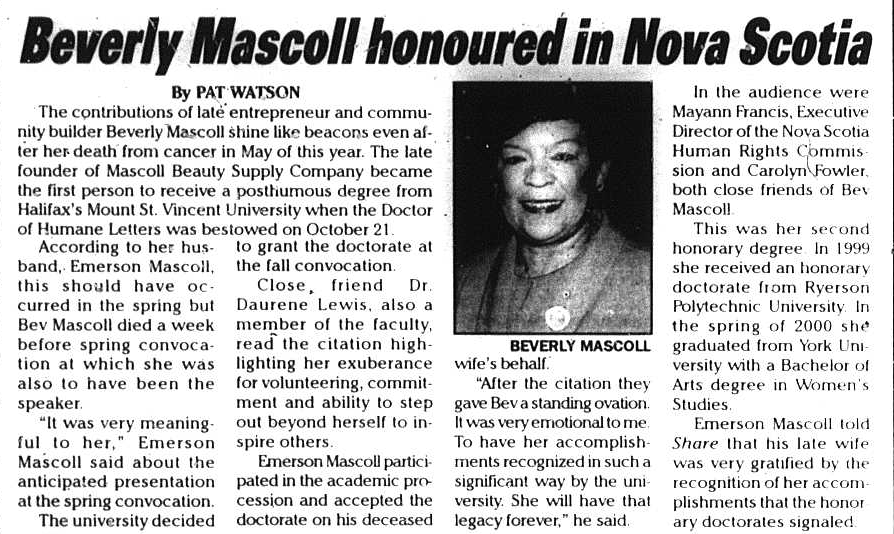

In 1993, she was the receipient of the YWCA of Metro Toronto’s “Woman of Distinction” award. In 1998, she was appointed a member of the Order of Canada in recognition of her community activism that included involvement in Black community organizatios such as the Harry Jerome Scholarship Fund, Camp Jumoke (a camp for children with Sickle Cell Anemia), and the fundraising efforts that led to the establishment of the first Black Canadian Studies program at Dalhousie University.

Even though Ryerson University’s Faculty of Business awarded Mascoll with an Honorary Doctorate of Laws in 1999, it was important for her to earn her degree. In 2000, in her 50s, she received her Bachelor of Arts degree from York University, in Women’s Studies.

Just a year later, Mascoll died of breast cancer. She was only 59 years old.

Her death left many in the Black community shaken and deeply saddened. Mascoll had been instrumental in the lives of so many people, myself included. I didn’t know her personally, but her store meant a lot to me. Mascoll Beauty Supply felt like family.

In a tribute to Mascoll printed in Share on May 31, 2001, George Bancroft, Professor Emeritus at the University of Toronto (he died in 2005), used poetry to capture the essence of Mascoll’s passing. He cited three phrases:

“Ask not for whom the bell tolls, it tolls for thee”; “For I am part of all that I’ve met” and the closing lines of James Shirley’s poem Death the Leveller, “Only the actions of the just/Smell sweet and blossom in the dust.”

In 2002, all Mascoll Beauty Supply were closed. Many of the locations became Shades of Beauty Supplies. While Mascoll and her stores have been gone for nearly 20 years, their absence is still felt. Many of the large Black beauty supply chain stores in the city are owned by Koreans, and while they sell quality products, what’s missing is the personal, one-on-one “hey sista-girl” service that helped make Mascoll’s more than just a business.

When we support our local, Black-owned beauty supply shop such as Sunrise or Ragga Hair Studio & Beauty Store or Kaks Hair Emporium in Scarborough, we do our part to keep the legacy of Beverly Mascoll alive.

Cheryl Thompson is an Assistant Professor in the School of Creative Industries, Ryerson University. Follow her on Twitter at @DrCherylT. This article includes excerpts from her new book, Beauty in a Box: Detangling the Roots of Canada’s Black Beauty Culture (Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2019).