This essay is a sequel to Natasha Henry’s account of the history of enslavement of Black people in Canada prior to 1834, published in Spacing last month.

Black Canadians deserve a formal apology for the history of the enslavement of African people in colonial Canada, accompanied by structural changes that address enslavement’s ever-present legacies.

In the ongoing public debate on this matter, some critics have argued against any apology or recognition of the 206-year history of the chattel enslavement of African people. They contend that Canada should not be held responsible for historic wrongs, such as the practice of enslavement, because it occurred during pre-Confederation times.

This disagreement is based on the position that enslavement was not practiced in Canada because Canada technically did not exist as a political entity until 1867, or 1982 when The Constitution Act ended the political power of the British Parliament to control/amend the Constitution of Canada. They lay the blame on French and British colonizers, who are described as the “two founding nations of Canada,” to the exclusion of the sovereign Indigenous nations that preceded a European presence by thousands of years.

I have observed that proponents of this argument proudly exalt the point that “Canada” was the first jurisdiction to abolish enslavement, and erroneously celebrate Lieutenant Governor John Graves Simcoe as having abolished this practice.

In the same breath, they smugly recite the narrative of “Canada” opening its arms to African American freedom seekers who escaped enslavement via the Underground Railroad, the secret network that operated until 1865, two years before the Dominion of Canada was established.

Dr. Charmaine Nelson, art historian and newly appointed Canada Research Chair in transatlantic Black diasporic art and community engagement, who will help set up the Institute for the Study of Canadian Slavery at the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, has posed the question, “What does it take to erase 200 years of history from the collective consciousness of a nation, but to enshrine three decades?”

I have also noticed that many enslavement cynics embrace the role of Queen Elizabeth II as Canada’s titular head of state. This continuous historical, political, legal, and practical relationship with the British Crown establishes Canada’s ongoing connection to the British monarchy, which was one of the earliest and largest European slave traders.

Queen Elizabeth I sponsored the expeditions of merchant and slave trader John Hawkins to Africa, where he procured captive Africans and traded them in the Caribbean. He also hijacked Portuguese slave ships, stole their cargo, and sold the pirated Africans, making a profit for investors including Queen Elizabeth I.

Canada’s enduring relationship with the British crown bears out Canadian culpability.

Other pre-confederate events are claimed as “Canadian”. When the question, “who won the War of 1812?” is posed, a chorus claims a “Canadian” victory over the U.S.

The name “Canada,” in reference to the colonized territories that became the nation-state, has been in use since the establishment of New France in the 16th century. The term “Canada” was used interchangeably with the term New France, and contemporaries of all backgrounds relied on this name to describe the northern French and British colonies.

Following British conquest in the Seven Years’ War in 1763, New France was renamed the Province of Quebec, and then divided it into Lower and Upper Canada in 1791. The Act of Union in 1840 formed the United Province of Canada, which merged the colonies but separated it into two parts, Canada East and Canada West. Not only was Canada used to describe political entities and boundaries; the “idea” of Canada was also prevalent.

Canada as a place appears in other contexts as well. Formerly enslaved African Americans, as well as free Blacks, talked about coming to “Canada,” according to various historical documents. The word “Canada” has even been used in a well-known abolitionist song, I’m on my Way to Canada:

“I’m on my way to Canada, That cold and distant land, The dire effects of slavery, I can no longer stand – … I’m on my way to Canada, Where coloured men are free.” (Joshua McCarter Simpson, 1852)

The evolving idea of Canada tells us about the identity of the society that early inhabitants thought they were building and the place they believed that they lived. In sum, the conceptualization of Canada in its early colonial iteration included the development of a state that employed the forced labour of enslaved Africans.

Those who deny or downplay the enslavement of African people in colonial Canada also point out that the majority of enslavement in pre-colonial and colonial Canada took place among Indigenous peoples, and, further, that all societies in the past had slavery. Some inaccurately expound about the fact that there were also white slaves in Canada, referring to European labourers who were indentured servants.

The view of Canadian enslavement cynics provides a window into the consequences of historical silence. The subjective selection of which historic wrongs are worthy of acknowledgement by the nation-state and some of its citizens serve to sever the legacies of Canada’s violent racist origins from its present representation as a welcoming multi-cultural oasis.

The routine efforts to divorce the realities of the enslavement of Africans from the dominant Canadian history narrative reveals the discomfort of white Canadians coming to terms with how enslavement has shaped them as well. Denial is a defense mechanism of white supremacy that is used to maintain a sense of superiority: moral, racial, or otherwise. It is a familiar way to silence conversation and serves to discredit the scholarship of Black academics and the voices of descendants of enslaved Africans who have asserted that Canada has a history of the enslavement of African people that must be acknowledged.

Some individuals have been dismissive of Black people’s perspective on enslavement, saying these events are in the past and that they should forget about them and move on. These familiar refrains will no doubt resurface in the comments section, primarily by white people who refuse to confront the truth.

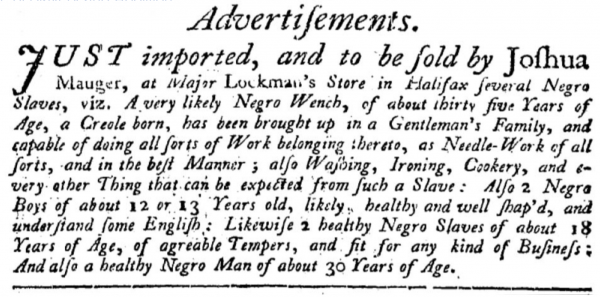

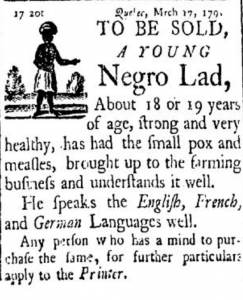

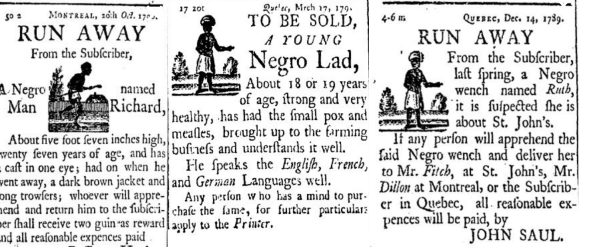

The efforts to deny the early subjugation of Black people on these colonized lands is an attempt to conjure a faux Canadian innocence that never existed. Additionally, the minimizing of the number of African people who were enslaved demonstrates a level of indifference for Black life. My doctoral research, One Too Many: The Enslavement of Africans in Early Ontario, 1760 – 1834, problematizes this position and aims to humanize of the African men, women, and children held in involuntary servitude and historicize them, no matter how many.

The efforts to deny the early subjugation of Black people on these colonized lands is an attempt to conjure a faux Canadian innocence that never existed. Additionally, the minimizing of the number of African people who were enslaved demonstrates a level of indifference for Black life. My doctoral research, One Too Many: The Enslavement of Africans in Early Ontario, 1760 – 1834, problematizes this position and aims to humanize of the African men, women, and children held in involuntary servitude and historicize them, no matter how many.

Recognition of enslavement as part of Canadian historical reality means acknowledging that the nation-building project of Canada was constructed on violence against Indigenous and Black peoples. The myopic perspective that Canada did not have slavery is also an indictment of history education that has sanitized country’s violent beginnings, perpetuated a narrative of innocence and exceptionalism, and romanticized the founding of the nation. Young Canadians have been taught to think uncritically about Canada as an arbitrary date instead of a set of complex relational processes.

Race-based enslavement precedes the nation-states of the Americas, including Canada, which means enslavement was a formal and integral part of their interconnected economic, social, and political foundations. The ruling Tory, French and Loyalist oligarchies in colonial Canada included enslavers such as McGill University founder James McGill, in Lower Canada; Mayor Gabriel George Ludlow, in New Brunswick; House of Assembly member James DeLancey, in Nova Scotia; and legislator Peter Russell, in Upper Canada.

The men who established and presided over the first governments and judicial systems are remembered as “founders” whose ideals are considered to be foundational to the beginnings of our nation-state. But their ideals were not limited to loyalism and reform. They included notions of race, enslavement, and racial hierarchies that shaped the formation of Canada. The colonial state sanctioned and protected the enslavement of Africans through contract law and legislation. For instance, the 1793 Act to Limit Slavery confirmed and maintained the hereditary status while introducing gradual abolition:

Provided always, That nothing herein contained shall extend, or be construed to extend to liberate any Negro, or other person subjected to such service as aforesaid, or to discharge them or any of them from the possession of the owner thereof, his or her executors, administrators or assigns, who shall have come or been brought into the Province, in conformity to the conditions prescribed by any authority for that purpose exercised, or by any Ordinance or Law of the Province of Quebec, or by Proclamation of any His Majesty’s Governors of the said Province for the time being, or of any Act of the Parliament of Great Britain, or shall have otherwise come into the possession of any person, by gift, bequest or bona fide purchase before the passing of this Act, whose property therein is hereby confirmed…

(An Act to Prevent the further Introduction of Slaves and to limit the Term of Contracts for Servitude, Statutes of Upper Canada, 33 George III, Cap. 7, 1793.)

Canada as a colonial product is also implicated in the transnational history of colonialism and enslavement.

Several Black Canadian scholars and activists, who have long been advocating for an apology, say that Canadians must own up to this history, and that the government must make amends. Dalhousie University professor Dr. Afua Cooper’s foundational scholarship has brought the history of the enslavement of Africans in Canada into public consciousness in her book, The Hanging of Angelique.

Further to this, Cooper initiated the commemoration of the Bicentenary of Abolition of the Slave Trade in Ontario and the City of Toronto in 2007, out of which came the first heritage plaque in Ontario to commemorate an enslaved person, Chloe Cooley, and the Archives of Ontario exhibit, Enslaved Africans in Upper Canada. Her poetry calls into the public mind the atrocities of enslavement.

Cooper has helped to lead the discourse and demands for an apology and reparations. “Canada’s political leaders, at all levels of government to offer an apology to African Canadians for slavery and other inhumane acts against Black people,” she says. “It’s high time that there be an apology; national, provincial, municipal apology to the Black community in this country.’’

In 2015, Cooper was appointed as the Chair of the Scholarly Panel on Lord Dalhousie’s Relationship to Race and Slavery and co-author of the Report, a scholarly inquiry undertaken to fully understand the school’s connections to enslavement in Nova Scotia, and how the institution and its benefactors benefited from the Transatlantic slave trade. Dalhousie has extended an apology to the African Nova Scotian community as part of the outcomes of the study.

Ellis Harding-Davis, a seventh-generation Black Canadian and past curator of the North American Black Historical Museum (now the Amherstburg Freedom Museum), has written to Prime Minister Justin Trudeau for a third time since 2018. She has also started a letter writing campaign to urge the prime minister to make a collective request for an apology for enslavement in Canada in light of the George Floyd murder that again sparked calls to address systemic racism. The prime minster acknowledged receipt of her last, but has not replied. His non-response exemplifies the ways in which the concerns of Black communities have been ignored by the federal government.

While an apology is long overdue, it is not sufficient on its own. An apology should be a starting point of a process that seeks to right the historic wrongs of anti-Black racism born out of the direct effects of enslavement as a means of addressing the ongoing racial and economic injustices and inter-generational trauma.

An apology should be followed by measures of reconciliation, redress and reparations as detailed in the program for the United Nations International Decade for People of African Descent (2015 – 2024) that the federal government, some provincial governments, and some institutions have endorsed.

However, government officials have likely received legal counsel against offering an apology because of concerns that it can be construed as an admission of guilt and thereby expose the federal government to legal and financial culpability. The state’s desire to limit its liability may be why political leaders and the federal government do not want to offer contrition.

However, the Black communities in Canada are demanding the Canadian government to be open to exploring what reparations could look like in response to the recommendations of the 2017 United Nations Report of the Working Group of Experts on People of African Descent on its Mission to Canada.

Dr. Michele Johnson of York University laid out the case for reparations in Canada in a recent interview. She outlines how reparations should be treated as reparative justice for Black Canadians beyond slavery to address systemic discrimination in education, employment, housing, and the justice system.

Johnson cites the restorative inquiry model used in the case of the Home for Colored Children in Nova Scotia, where the provincial government issued an apology in 2014 and made modest reparations to the affected community. Johnson further argues that it is time for provincial and federal governments to apply the recommendations that have come out of multiple reports and studies in legislation and policy to remove the incredible barriers that Black Canadians face. Governments, she says, should take a systemic approach and develop a mechanism to deal with individual claims.

Lynn Jones, long time activist and chair of the Nova Scotia chapter of the Global Afrikan Congress, is another person who has long advocated for reparations for African Nova Scotians who have suffered systemic historical injustices. Both Jones and Saint Mary’s University Assistant Professor Dr. Rachel Zellars have called for educational scholarships and the establishment of Africentric schools, targeted political and leadership representation, and land claims for displaced African Nova Scotians.

They also argue that reparations should include compensation for African Nova Scotians victims of the 1917 Halifax Explosion, whose claims were systematically denied. A third aspect of reparations that they propose is the creation of Black studies research institutes, where Black scholars can investigate and design plans to administer reparations.

To date, Canada has rightfully issued several apologies accompanied by compensation in recognition of past wrongs and mistreatment of several groups. Japanese Canadians received an apology in 1988 for internment during the Second World War. The federal government apologized to Chinese Canadians for the Chinese head tax in 2006. Parliament has apologized to First Nations, Metis, and Inuit people for residential schools, first in 2008 and again 2017 to include Newfoundland pre-1949.

The federal government has also acknowledged the internment of Ukrainian Canadians and Canadians from Eastern Europe during the First World War in 2008, and in 2016 issued an apology to Sikh Canadians for turning away the Komagata Maru in 1914. The most recent apology occurred in 2017, when Justin Trudeau delivered an apology to LGBTQ Canadian civil servants and members of the military for decades of “state-sponsored, systematic oppression and rejection.”

These apologies were for historic injustices that took place after 1867 and confederation. It is also worth noting that Queen Elizabeth II apologized for the Acadian Expulsion in 2003, a pre-Confederation wrong, but was careful to include a disclaimer barring legal and financial liability.

One group is conspicuous by its absence. “While other groups have received apologies for acts of discrimination and racism,” says Cooper, “no such gesture has been forthcoming to the Black community in Canada…It’s almost like people don’t want to apologize to Black people.”

It is true that history cannot be reversed; the past is the past. But Canada needs to learn from its complicated history and reckon with its past of enslavement by acknowledging how the historical processes born out of chattel enslavement created the present conditions that stifle Black life: 206 years of racial human bondage; over a century of legal and de facto racial segregation by state and public institutions such as education, housing and employment, disproportionate representation in the criminal justice system and child welfare; historical disparities in social outcomes; and entrenched second-class citizenship. These legacies of enslavement have ethical dimensions in contemporary Canada that necessitate action.

The federal government can take the lead by issuing a formal apology and making amends to Black Canadians who have been systematically oppressed and disadvantaged. This first step should lead the way to reconciliation, with various measures to facilitate truth telling, including the integration of Black experiences in the curriculum; the creation markers of memory, like plaques and monuments; and the establishment of spaces for learning such as museums.

The process of reparatory justice must also include prescriptive collective repair administered to Black Canadians to change the material conditions of Black life. Reparations that aim to dismantle systemic anti-Black racism and move towards equitable outcomes would benefit all Canadians. A sincere apology to Black Canadians, not merely a watered down statement of regret, can usher in healing and also help to reset Canadian history, modelling a vision of Canada that steps up to its responsibilities of all of its citizens.

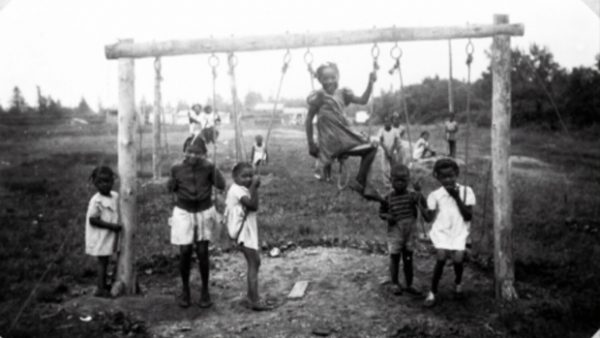

In this historical moment in 2020, with the surging Black Lives Matter movement amidst a global pandemic, Black Canadian children and other Black folxs are marching in the streets for justice, for their humanity to be honoured, and for their human rights to be upheld. They are bravely challenging the status quo, calling for it to be dismantled and demanding that state and institutional leaders go beyond scripted PR statements to acknowledge as a basic premise that systemic racism exists and disproportionately affects Black and Indigenous peoples.

If the lives of Black Canadians are of genuine concern, then an apology, reconciliation, and reparations would be true demonstrations of political commitment and action towards meaningful progressive change.

Emancipation Day, August 1, would be an opportune time to take this courageous first step.

Natasha Henry is a 2018 Vanier Scholar completing a PhD in History at York University on the enslavement of Africans in early Ontario. She is the president of the Ontario Black History Society (@OBHistory) and has written previously about the politics and history of enslavement in Canada for Spacing. Follow her on twitter at @NHenryFundi.