For thousands of Toronto residents, housing precarity and homelessness are a lived reality. But for many others, the issue grew suddenly more visible as encampments were established throughout the city in the spring of this year. That lived reality is a harsh one: despite the move to two-metre distancing between shelter beds, there have been 649 cases of COVID-19 reported in the City of Toronto’s shelter system, which serves approximately 7,000 people per night, meaning a 9% infection rate. The overall reported numbers in the City of Toronto have an infection rate of 0.62% (18,107 in a population of 2,956,024). In short, it’s clear that the risk of contracting COVID-19 is substantially higher for those who use shelters.

Though the pandemic has foregrounded shortcomings within Toronto’s shelter system, it hasn’t revealed anything new — at least not to those familiar with the facilities. Health profiles have consistently shown that the communities with the worst access to housing have the poorest health. Buildings that are over-crowded and under-serviced increase the potential for the spread of communicable diseases. And this spread has dire consequences: the overall death rate is 8-10% higher for people experiencing homelessness than for housed people of the same age.

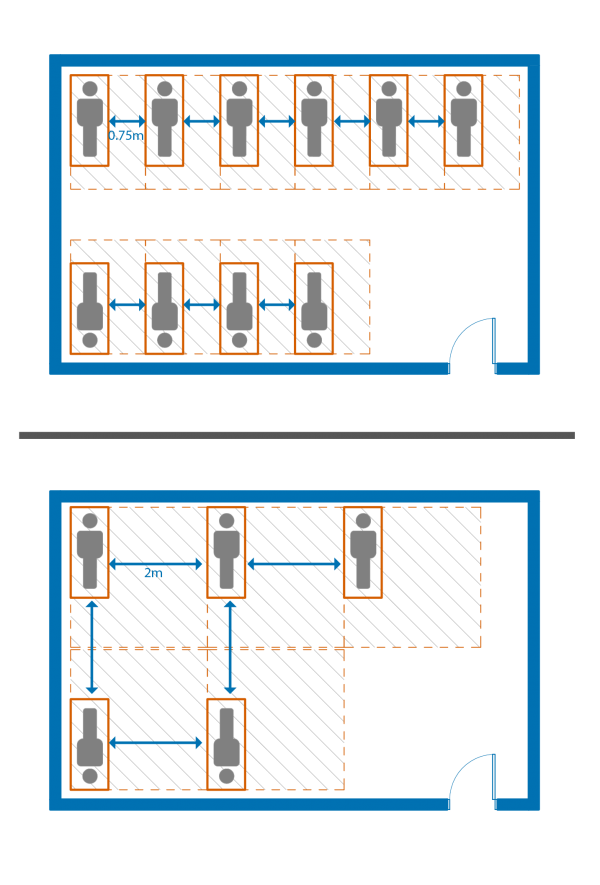

The City of Toronto’s shelter standards pre-COVID list the following criteria for client privacy and personal space:

- A single bed layout that complies with a personal bedroom space requirement of minimum of 3.75m² (37.7ft²);

- Lateral separation distance of 0.75m (2’6”) between beds;

- Bunk beds that provide a minimum of 1.1m (3’6”) of overhead clearance.

In addition to the numbers above, these standards do not mandate a limit on beds per room or client common areas.

Figure 1: Potential room layout following current shelter standard personal space area versus space required to maintain 6’ of physical distancing

While the City adopted new measures in shelter spaces for social distancing during the pandemic, increasing the distance between beds to at least two metres, disallowing bunk beds, and decreasing the population in most shelters by 40-50%, the current design criteria still falls short of complying with public health guidelines. Since April, 33 temporary facilities, including hotels and vacant buildings have been opened by the City of Toronto to allow for distancing that better adheres to these requirements. The 1,000-2,000 people currently living in encampments around the city, which have had no reported cases of COVID-19, suggests that these new shelters do not meet client needs.

New shelters are constructed following guidelines set out by Toronto Shelter Standards and written/amended in consultation with former and current clients . Reports such as the Toronto Street Needs Assessment (SNA) and groups like the Encampment Support Network overwhelmingly advocate for an increase in permanent housing over shelters, highlighting a disparity between the buildings requested by people experiencing housing insecurity and the architecture that the City actually provides.

Despite the policy-makers’ best efforts to mandate consultation, clients of Toronto’s shelter system still feel that the emergency respite facilities provided are inadequate as a primary building typology to address homelessness or housing insecurity. Toronto City Council is currently voting on a number of recommendations from The Planning and Housing Committee to leverage The City’s resources and intergovernmental partnerships. Recommendations include reallocating operating resources from those respite centres made unviable by physical distancing to alternative housing supports. If this decision by council passes, it could lead to the creation of 3,000 affordable rental and supportive homes. However, if we hope to make meaningful change, it’s essential that we not only modify policy, but revisit the core role of architecture and design in shelter spaces and public housing.

Health and Dignity in Design Guidelines

Building codes and architectural policies/guidelines for private residences ensure that spaces where people live are not overcrowded, and homes are designed to give each occupant a reasonable amount of privacy. But when it comes to policy and design for people experiencing housing insecurity or homelessness, these principles are left behind. The guidelines center operator needs: efficiency, affordability and public discretion, not the needs of those living there. If architects already know how to apply compassionate design in their work for private housing, why can’t they apply the same principles when designing for people experiencing homelessness?

The problem is a complex one. Gary Bloch, a physician at St. Michael’s Hospital who specializes in inner city health, says there is no secret in designing for the reduction of infection spread; you just follow the rules. However, the guidelines only establish the bare minimum and Bloch believes that a critical element is missing from the typical public health agenda:

“So, if our public health goal is to get people into safe spaces and out of homelessness, and deep poverty, and social isolation, and all the other points to their social marginalization, like to me, the conception of what a safe homeless shelter would look like becomes very different, right? This is not about having hand sanitizer stations spread around, or having 2m between beds. This becomes much more about having spaces that are truly dignified.”

He also notes that when people have safe spaces to call home, they recover faster. And the definition of safety should be more than the bare minimum: to make a healthy shelter, one has to design compassionately, with dignity in mind. It’s a delicate balance between operator and resident criteria, so how does this translate spatially?

We spoke to Melanie Randall, Project Manager at Surrey Place Centre, about what a shelter designed with dignity looks like. She notes that spaces which allow for both personal and interpersonal intimacy are key elements. There may not be a one size fits all solution — but we need to incorporate this criteria into both respite shelters and supportive rapid response housing.

Randall also emphasizes that existing and proposed respite shelters could benefit from adjustments, such as making spaces available where one can opt for privacy and ownership of space, or ensuring that there is no hierarchy between operator staff and client residents.

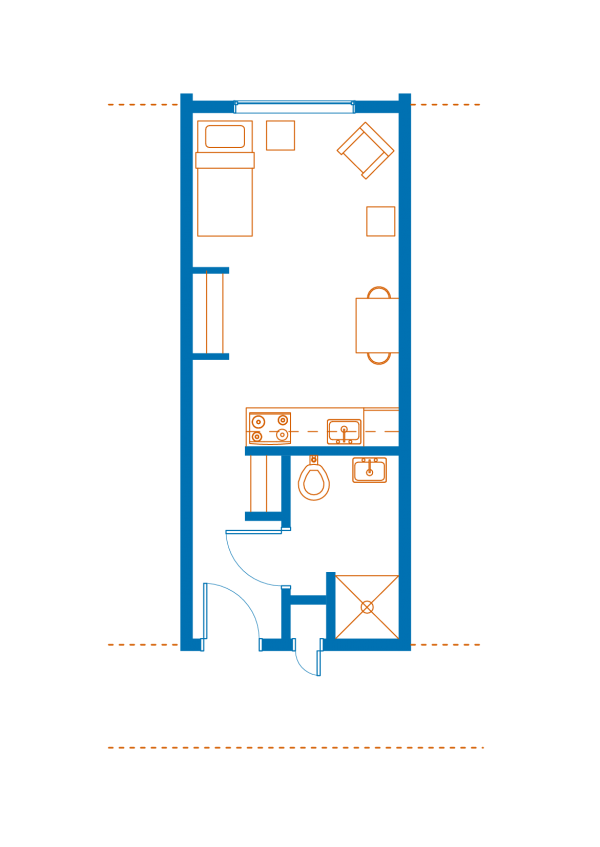

Figure 2: Diagrammatic floor plan of a typical shelter space based off of Toronto Shelter Standards, with adjustments for new social distancing guidelines

The City’s standard plans typically consist of shared rooms and common areas for dining and social activity, with clear, often physical, delineation between those spaces meant for staff and those meant for clients. And while separate spaces for staff is required for security, those paces should not communicate a power imbalance. “I worked with one person who couldn’t use her sleep apnea machine because there was no private space to sleep, and no private place to rest during the day” recalls Randall. “That’s a health concern.”.

While she notes that some shelter operators are proactive in carving out private spaces for residents, it is ultimately up to the operator to incorporate any measures beyond the guidelines. By writing these elements into building standards, we can ensure a baseline of dignity is provided to all residents.

Taking things a step further, some municipalities have decided to design for privacy and dignity first, doing away with the traditional shelter structure entirely. Lauded by residents, Marpole, Vancouver’s modular housing experiment, exemplifies the philosophy that Randall describes. Initiated as a rapid response program, Marpole (architect Boni Maddison) makes use of standard modular units erected to accommodate a variety of site conditions. Each unit consists of an individual suite, complete with a kitchenette and private washroom.

Figure 3: Typical unit floor plan at Marpole

Residents are provided with meals and connections to community groups as well as access to support options, such as life-skills training, health resources, and social services. While some may benefit from closer supports such as harm reduction and/or mental health resources, this approach does begin to shape the picture of what designing with compassion looks like when one considers housing insecurity and those experiencing homelessness.

Compassionate Building in Public Policy

Supportive and permanent housing will not completely eliminate the need for respite shelters, but it could offer much needed relief on an overburdened shelter system. Toronto’s Shelter Support & Housing Administration’s (SSHA) 2020 program summary reports that it continues to be challenged with an extremely high demand for temporary emergency respite facilities. Yet the vast majority of shelter users indicate a desire for more permanent, affordable housing. In addition to the growing demand for emergency shelters, the 2018 Toronto Street Needs Assessment report cautions that the spike in the number of people in need of respite housing is due to an influx in refugee populations, with refugee/asylum claimants accounting for 40% of those staying in City-administered shelters. This poses the question: why are refugees/asylum claimants being funneled into emergency respite facilities in lieu of longer-term social or supportive housing?

From the mid-1980’s to the mid-1990’s, the federal government cut funding for social housing construction, putting an end to the yearly construction of approximately 20,000 new social housing units. Following these cuts, the homelessness crisis worsened, prompting an increase in advocacy, and the eventual return of some federal funding.

Notably, construction funds for shelters and supportive housing were reinstated by the end of the decade. When federal support was initially cut, and few consistent funding methods remained, responsibility for social housing fell to the provinces, which in turn offloaded the costs to municipalities without notable funding support. The lack of adequate capital for construction may partially explain Toronto’s focus on shelters over more permanent housing options in recent decades. But the cumulative operational costs of these facilities is mounting, and demand for additional housing solutions has grown. The social housing waitlist exceeds 100,000 and there are another 14,000 people on the supportive housing waitlist, a figure that has quadrupled in the last decade.

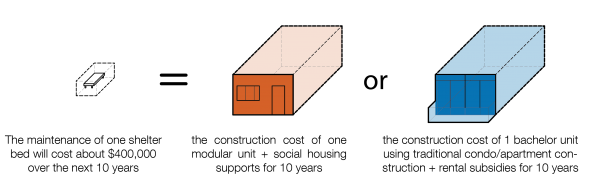

Financial pressures notwithstanding, there are opportunities to provide proactive solutions (permanent housing) rather than reactive (shelter housing) for the same outlay. This shift would address the building typologies requested from housing advocates and people experiencing housing insecurity. The Wellesley’s Institute’s Blueprint to End Homelessness in Toronto has consistently reported that municipal taxpayers are paying ten times more to keep a homeless person on a cot in a shelter than to provide them with good quality social housing.

The initial capital costs of better architecture for the underhoused may seem like an obstacle, but the research shows that returns on this investment can be seen in both direct and indirect ways. For example, Toronto’s Interim Shelter Recovery Strategy notes that people experiencing homelessness are 5 times more likely to be hospitalized than the general public, and with longer stays, which average a monthly cost of $10,900 per person.

Figure 4: Comparison of operational costs for an existing shelter bed against providing new, alternative housing

The City has recognized the need for proactive housing solutions and has nominally committed to providing 40,000 new affordable housing units, and 18,000 supportive housing units, as part of its HousingTO 2020-2030 action plan. The units are necessary to reduce strain on the shelter system and waiting lists and operational costs.

While the results of the 2010-2020 affordable housing action plan may inspire skepticism (just 4,093 of the planned 10,000 new affordable housing units, were completed, and only 613 were deeply affordable), there is room for architectural intervention to offer proven and rapid construction housing typologies.

Like in Marpole, modular housing has recently been proposed by the City of Toronto as an achievable solution to shortages in housing and the overloaded shelter system. It has been a welcome idea to many, given that there has been such a marked decline in the construction of social housing.

Thus far, the City has committed to creating 1,000 new modular homes in Toronto within the next ten years. Modular construction is an effective way to construct quickly. While this commitment won’t necessarily solve the crisis of housing for Toronto, it could be an effective vehicle to house chronically homeless populations and those in need of supportive housing. If it works well, modular housing could also provide proof that Toronto is capable of building its own housing at reasonable construction costs.

Time will tell if modular housing is an effective tool to address homelessness. In the mean time, we must look forward to design guidelines and public policies that center dignity, independence and a renewed focus on permanent housing solutions. The City has an obligation to listen to shelter residents’ demands and follow through on commitments to address Toronto’s housing crisis.

The potential for rapid construction, modular housing to disrupt the current crisis presents a much needed opportunity for optimism, and it’s essential that the City invest heavily in these approaches. But there isn’t time to be idle. Architecture and design must revisit the approach to shelters and respite centers, offering residents spaces that center dignity and independence. They’ve asked for change, and it’s time the City delivered.

Kellie Chin and Naomi Shewchuk are intern architects. Their research into health and housing has been supported by the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada (RAIC)’s Foundation Bursary, the Ontario Association of Architects (OAA) and WORKSHOP (IG: @Workshoparchto).

One comment

Well done Kellie. Looking forward to your next visit to PEI – stay safe in the big city.