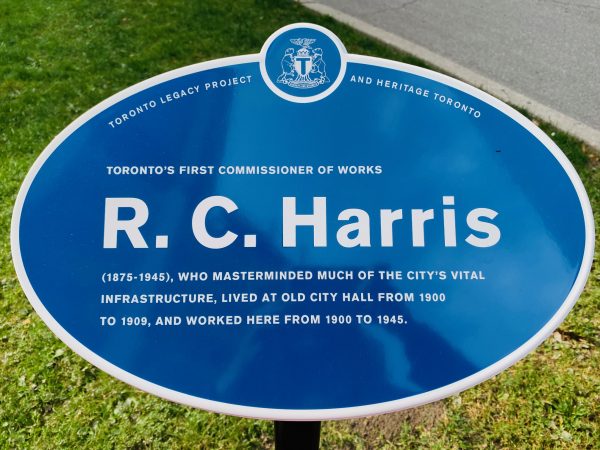

Anyone venturing by the Queen Street side of Old City Hall in the past couple of weeks may have noticed a small new plaque in front of E.J. Lennox’s monumental sandstone castle – one of the Toronto Legacy Project’s blue oval markers denoting the former dwelling of a well known resident. (Heritage Toronto is a partner.)

This one, the 50th to be installed, honours Roland Caldwell Harris, the City’s longest-serving works commissioner (1912-1945), and, in many ways, the architect of so much of early 20th century Toronto.

Harris was the bureaucratic force behind the east end water filtration plant that bears his name, the Prince Edward Viaduct, many smaller bridges, the civic streetcar system and other fixtures of the older city. Far less well known is that he and his young family lived at Old City Hall, in the third-floor janitor’s apartments, now provincial offenses courts, between 1900 and 1909.

Thus the plaque in that location.

Credit for the biographical discovery goes to lawyer and author Jane Fairburn, who was asked to carry out this bit of sleuthing by former Toronto poet lauterate Dennis Lee, who founded the TLP in 2002.

Triangulating from city directories, Goad’s fire insurance maps, City of Toronto municipal handbooks, and architectural blue prints and floor plans of Old City Hall, Fairburn was able to pinpoint the location of the works department over which Harris presided for 33 years — a suite of offices at the south-east corner of the main floor.

But Fairburn’s reconstruction of his residential addresses — from childhood to his death — offers some salient insights about what made Harris tick.

Though he was born in the Lansing neighbourhood (now a part of Willowdale), Harris lived during part of his early childhood with his mother, Kate, on Saulter Street, in what is now Leslieville.

The precise location of their dwelling isn’t clear, but Fairburn points out that the street dead-ended onto one of the more notorious sources of pollution along the city’s industrial waterfront. The site housed large cattle byres owned by Gooderham & Worts, which pumped the grainy residue from its distillery across the lower Don, to be used as feed for the cows. Their manure, in turn, was shoveled into Ashbridges Bay, a fetid and apparently malarial marsh that would eventually be filled in to create the Port Lands. Harris, who lived on Saulter from ages 5 to 10, would certainly have been aware of the stink that made Ashbridge’s Bay so detested.

Kate worked as a cleaner at City Hall – then St. Lawrence Hall – and young Roland ended up working there as a clerk by his teens, at which point mother and son were living on what is now Adelaide Street East, near Parliament.

Harris was 25 and newly married, to Alice Ingram, when they moved in 1900 into the janitor’s apartments at Toronto’s just completed city hall at Queen and Bay.

He’d spend most of the next 45 years there. As Fairburn wrote in her research brief in support of the plaque, “[Harris] went from assistant caretaker (1900) to chief clerk in the City Commissioner’s Department (1903) to chief clerk in the Department of Assessment (1904) to chief clerk in the Assessment and Property Department (1905) to Commissioner of Property (1906) to Commissioner of Property and Street Cleaning (1911) to the newly-created post, Commissioner of Works and Chief Engineer (1912).” She describes his climb as “meteoric.”

Harris came of age during the Progressive era, when urban reformers across North America were looking to professionalize municipal administrations, push back against Tammany Hall-style corruption, and bring about a range of changes, from improved public health systems to better parks and infrastructure.

His record suggests he subscribed to these ideals, but Fairburn notes that Harris, an avid photographer, also had a vision of the city – “a strong beauty aesthetic” – as well as a clear interest in the waterfront. An album of his photos is filled with images of the lakeshore and the water’s edge. After 1909, he and his family moved to The Beach, first to Balsam Ave. and then into a stately house at the bottom of Neville Park Blvd., which afforded an unobstructed view of the lake and the park that would, in the 1930s, become the city’s majestic Art Deco water treatment plant.

However, the question implicitly posed by the location of the new plaque is what it was like for Harris and his young family – the couple had three children, one of whom died of an infectious disease in 1906 — to be living right inside City Hall?

Without too much difficulty, you can imagine your way into that peculiar life. When the building emptied out in the late afternoon, as the clerks and officials went to their homes outside the core, the Harrises probably had the place to themselves – the wide, echo-ing corridors, the spooky, unfinished fourth floor, beneath the eaves, the decorous city council chamber, with its elaborate carved wood paneling.

One other important detail emerges: their apartment overlooked the southern blocks of The Ward, across what was then Terauley Street, now Bay. Harris would have been able to see beyond the commercial buildings lining the west side of Terauley and into the derelict backyards and rear laneways, jammed as they were with privies and heaps of junk and shacks rented out to poor immigrant families.

What did the future works commissioner ponder, late at night as he pushed a broom around that immense building or looked out over the poverty next door?

No one will ever know. Harris left no diary, Fairburn points out. “He’ll always be a bit of a mystery.” But the new plaque invites us to speculate.

3 comments

Harris’ rise from janitor to commissioner is indeed an accomplishment, and described as meteoric. In First Nation terms, he plummeted from the top of the totem pole to “low man”. It turns out that the low position holds the highest honor because it is the most visible. Harris worked his way from obscurity to high profile which now includes the plaque. A diary of Harris’ plans, thoughts, etc. as he rose in the ranks most certainly would have been an interesting read!

A great Toronto visionary!

I have long admired the works that R.C. undertook for the betterment of this city and their resulting legacy. I often visit his grave in the St. John’s Norway Cemetery as it is close to where I live. The wording on his headstone says it all: No ostentation mark’d his tranquil ways; his duties all discharged without display.