The university students behind Scarborough’s first bicycle path couldn’t have predicted that it would one day provide a lifeline to cooped-up families during a global pandemic. In fact, had the students gotten their way a half century ago, the path they proposed would have run at least 15 km instead of barely five.

The “Bicycle Revival” of the early 1970s brought thousands of adults back to cycling, only to discover an obvious obstacle – there were too few safe places to ride. Scarborough, then part of Metro Toronto (now the amalgamated city) was no different, but students at the University of Toronto’s suburban Scarborough campus came up with some solutions. After forming a wing of the fledgling environmental organization Pollution Probe, they mapped out a bikeway system, including a hydro corridor route from the Warden subway station to the Metro Zoo, then under construction.

In April 1972, the students, led by Norm Hawirko, appeared before Scarborough’s Board of Control, confident in their plan. They had already met with city and hydro officials, secured government grants, and even promised to build the proposed path at no cost to the city. But they were quickly disappointed.

Some controllers worried about the loss of tax revenues to the city from taking over a portion of the hydro corridor, especially for a path that might be used by non-residents. Instead of approving the student initiative, the parks commissioner proposed an alternate 5-kilometre route along a branch of the Highland Creek. Hawirko described the proposed path as starting nowhere and going nowhere. “Well, you’ve got to start small,” the mayor told him.

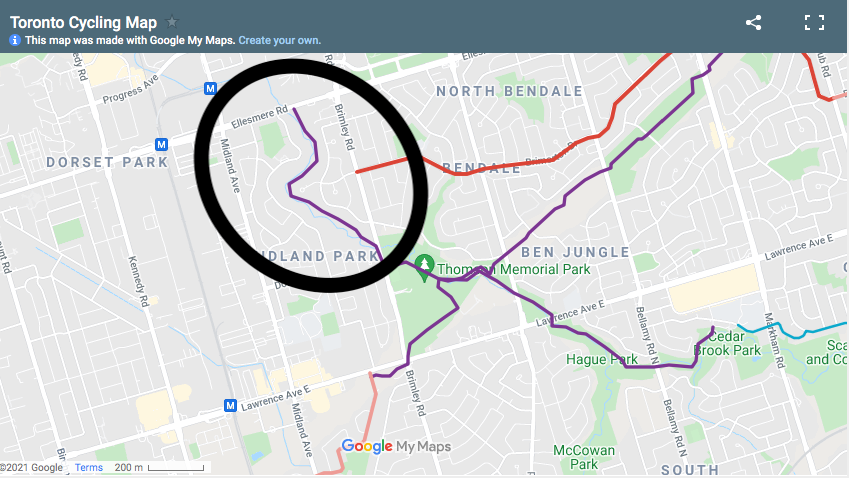

The students weren’t easily discouraged, indeed “nothing would cloud our view,” recalls Hawirko, quickly converting disappointment to action. A landscape design student mapped out a 1.5 km route in the Birkdale Ravine (running diagonally between Ellesmere and Brimley Roads), while another student, with construction experience and a borrowed front-end loader to clear the path, proved that the project was figuratively and literally ground-breaking. Hawirko kept the group on track, while demonstrating the bicycle’s versatility, betting that he could cycle the entire length of the path in the creek itself. (He almost succeeded, thwarted only by a rock.)

After completion of the path, the city added a new frustration, refusing to issue receipts to companies that had made in-kind donations of materials. “They’ve tried to block us at every turn,” complained student Leonard Steele. “[T]his is the thanks you get.” The council must nonetheless have recognized the value of the path for cyclists and people on foot, later extending it by over three km from Thomson Park (on the opposite side of Brimley) to Cedar Brook Park.

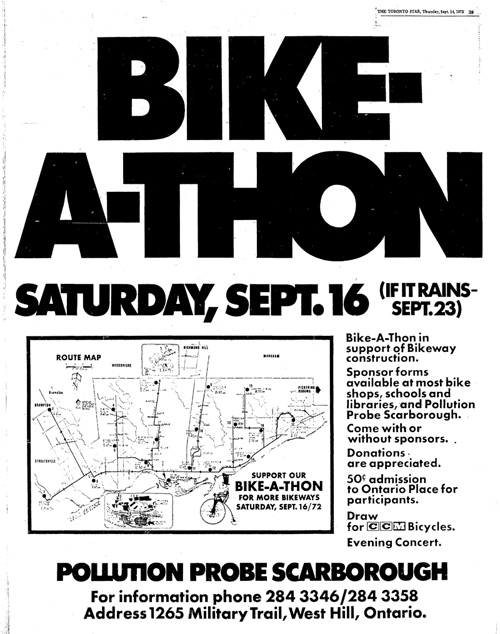

The students’ continued to push for more bike paths, organizing a Bike-a-Thon to rally support for more bikeways across Metro. Hundreds of cyclists, from eight distant starting points, converged at Ontario Place on September 16, 1972, a day that Mayor William Dennison of the old city of Toronto declared “Bicyclists’ Day.”

Two years later, Metro Council unveiled its own plan setting out 400 km of “arterial” bike trails, but with a controversial catch — it wanted to get cyclists off arterial roads. Metro, however, never quite mustered the energy even to complete the 125-km phase one, deciding in 1982 that the construction challenges were insurmountable or threatened sensitive natural areas – a curious conclusion given that it had then recently flattened hills and altered a water course to build the Don Valley expressway.

Hawirko, now living in northern Ontario (where he recently contributed to the mapping of bike routes around Temiskaming Shores (PDF)), has become magnanimous about the Scarborough mayor’s rejection of the student proposal, saying that the alternative bike path, wholly within city property, facilitated the path’s swift completion. On the other hand, the students, then in their twenties, couldn’t have imagined that when they reached their seventies Scarborough’s scattered bike trails (often best accessed by car with a bike on the roof) and bike lanes would still be a patchwork instead of a network.

The fight for safe cycling infrastructure in Scarborough has been taken up by a new generation of advocates, with preoccupations that now include climate change. The Toronto East Cyclists are pushing for bikeways that would make it safe to cycle to work, school, or shop, including among their initiatives a bike lane on Ellesmere Road, which would add value to bikeways such as the Birkdale Ravine path.

One day, city residents may be able to cycle to the zoo from various parts of the city, as the students long ago envisioned. In fact, The Meadoway, a Toronto and Region Conservation Area (TRCA) project, with Weston family funding, to create a 16-kilometre linear park is already underway, although it will take at least three more years to close large gaps in the Gatineau Hydro Corridor bike path.

The Scarborough students of the 1970s saw a need for safe bike paths, rolled up their sleeves, and got to work, undeterred by the lack of political ambition. Today, when residents enjoy a respite from the pandemic with a breath of fresh air and exercise on the Birkdale path, they have the pioneering students to thank.

Images courtesy of Albert Koehl. Top image: Norm Hawirko on the Birkdale Ravine bike path, 2019

Albert Koehl is an environmental lawyer, road safety advocate, and a founder of the Toronto Community Bikeways Coalition.