An excerpt from Indigenous Toronto (Coach House, 2021) on National Truth and Reconciliation Day.

“We show them spirituality and love and try to teach by example.”

– Elder Vern Harper“Unless we know the legends and the stories of Creation, unless we know the songs and ceremonies, we don’t really know who we are.”

–Elder Jim Dumont (Onaubinisay/Walks above the Ground)

Toronto is defined by its strata of buildings, its paved public spaces, and its hum of human activity. In many ways, this city defines one’s connection to the earth. Elder Madeline Skead, from Kenora, Ont., in awe of the immense and unnatural landscape of the city, once remarked to my father: “Where can you put down your tobacco here?”

Madeline, who passed away in 2012, was a beloved teacher and rights advocate whose name is celebrated across many parts of Ontario and beyond. As a mentor and spiritual guide to my own family, her question has lingered in my mind for the 20 years I’ve spent living in T’karonto. This city teaches us a way to live in a human-centered environment – where the focus is on what humans can build upon and consume, rather than on our responsibilities to the earth. Where can we communicate with what is sacred? Where can we put down our tobacco?

Over the past two decades, Elder Pauline Shirt has been one of my most important teachers, helping me to answer such questions by listening to the Indigenous community, to my own heart, and to the earth. Pauline (Nimkiikwe), is a Plains Cree Elder originally from Saddle Lake, Alberta, Red-Tail Hawk Clan, and member of the Three Fires Society (Midewiwin) and Buffalo Dance Society. Informed by her own Plains Cree culture, Pauline has dedicated her life to providing people with ceremony and guidance, and to cultivating spaces in this city that offer an Indigenous approach to education.

Pauline offhandedly told me that she comes from “a family of chiefs and go-getters,” but until I sat down with her for this article, I had no sense of the depth of her statement. She is currently the Elder at George Brown College, is on the Elders Council for the Urban Indigenous Education Centre of Excellence, and is endlessly called upon by organizations and community members for her fearless-yet-kind direction and rich cultural knowledge. Pauline’s unwavering commitment to education crystalized when she, with support from her late husband Vern Harper, started Wandering Spirit Survival School – a school that would teach children living in Toronto about Indigenous ways of life. It became the first Native-led school founded in Canada.

I wanted to sit with Pauline to understand her vision for the school, and the history that shaped its creation. When Pauline and I spoke, it was in the middle of the pandemic lock-down in May 2020, and she, in her nomadic ways, had moved temporarily to Six Nations. One thing that continuously draws me to Pauline is her buoyant energy, and even my cell phone didn’t stifle the feeling of delight she radiated in being able to talk about her “favourite subject.” Pauline said, almost effervescently, “The school produced so many successful souls. To this day, there are lots of good stories. So many good things happen that I could just sit here for weeks and tell you all of the beautiful things that happened!”

In my eagerness to direct the interview, I began to review my list of questions when she warmly interrupted. “I will just talk, and the answers will come through in the story.” As I allowed Pauline’s words to wash over me, it became clear that like any river, her story of the school had many tributaries that shaped and nourished it. One tributary was her son Clayton, who refused to return to the public school he attended. Protesting against the racist schoolyard bullying and general disconnection from the curriculum and pedagogy, Clayton’s actions, combined with the lack of other culturally safe schools in Toronto and across the country, strengthened Pauline’s resolve to start a school where her Indigenous way of life could be taught and celebrated. Though her son’s daring protest further stirred her spirit to action, the spirit of the school itself preceded young Clayton by seven generations.

Wandering Spirit (Kapapamahchakwew), a hero of his people, is the namesake of the school, and what he represented to Pauline was a spirit she wanted to foster in her children and the larger community. Known as a key player in The Frog Lake Uprising of April 2, 1885, Wandering Spirit was a skilled Cree War Chief whose partner-in-leadership was the famed Cree Peace Chief, Big Bear (Mistahimaskwa), known as the last Cree leader to resist acquiescing to treaty.

The history of the uprising is disputed and most certainly incomplete. In short, dependence on government rations took hold as buffalo became scarce and were killed as a strategy to starve Indigenous bands onto reserves. Coupled with fighting with the neighboring Blackfoot, Big Bear’s band of Plains Cree were relocated by the Canadian government close to Frog Lake, an area 24 kilometres long, connected by a creek to the Saskatchewan River. Prior to April, 1885, the government had continuously failed to provide promised rations or uphold the agreed-upon rights, leaving the band starving and badly impoverished.

Renowned for his tenacity and strategic intellect, Wandering Spirit joined a group of young braves after they had confronted a reviled Indian Agent, Thomas Quinn, known to both the RCMP and the Plains Cree band for mistreating Indians and withholding rations. This encounter resulted in Quinn being shot and killed, and in the killing of several other townspeople.

Ten days later, on April 12, Wandering Spirit and 200 Cree moved on to capture Fort Pitt, that held military supplies and other useful provisions. Sources on this history are again conflicted. Some align Wandering Spirit with Louis Riel and his resistance while others suggest Wandering Spirit and Big Bear’s refusal of Riel’s invitations. Following the RCMP’s surrender of Fort Pitt, the War Chief and his followers travelled through the woods to avoid imprisonment, but surrendered some months later. Wandering Spirit was hanged at Battleford with others accused of participating in the North-West Resistance, though none of the accused were provided with translation or legal counsel at their trial. It is said that at his death, while others cried out in defiance, Wandering Spirit sang softly to his wife.

When Wandering Spirit’s name was unspoken

Mainstream schools have taught children that Louis Riel, Big Bear and Wandering Spirit were traitors, and misunderstandings about the details of these incidents have been retold by community members for decades. Notwithstanding this imperfect historical memory, Wandering Spirit’s goal of independence and his fight against starvation were resolute and irrefutably determined his actions. Despite his dedication to his people, Wandering Spirit’s name was unspoken on Pauline’s reserve for nearly six generations. When she began the school, Pauline was unaware of her close blood ties to him. Her family held their silence for generations as they had been disgraced with the label, “your-Grandfather-killed” — a saying that underscored the shunning of Wandering Spirit for being labelled as ‘a killer of your own’ and the community’s cultural prohibition against being the first to raise your weapon. Today, Pauline celebrates his name and the indomitable spirit that sought a better future for his community.

As poet and author Sharon Berg writes in her book, The Name Unspoken: Wandering Spirit Survival School:

Pauline named her school after him in order to re-establish his name with honour in his own community. In Pauline’s understanding, he had shouldered the blame for circumstances that were far beyond his control in 1885. As a warrior, his life was devoted to protecting his nation and Wandering Spirit did his best to protect his band during the events leading up to the Frog Lake uprising and their months-long trek through the forests… Even with his last breath, Wandering Spirit urged his people to continue practicing their cultural ways in the death song he sang for his wife.

…Pauline heard from people who knew the true story, different than the story recorded for posterity. The shooting of Thomas Quinn was shifted to Wandering Spirit’s shoulders to protect a younger brave. That’s why his name was unspoken in Pauline’s family for almost 100 years. She wanted to correct the wrong done to him, even as she worked to correct the wrongs done to her people.

The story of her grandfather, six generations removed, is certainly a tributary for Pauline’s vision. Another is her family in Alberta, and growing up on a farm where she was her father’s shadow. She learned “how to work in a circle, together as a family, to respect and love each other.”

Being Dad’s helper, that’s how I learned to take care of Mother Earth Dad was always talking to the spirits, talking to the horses, animals, and plants. He showed me what a relationship to the earth looks like. While he was tilling the fields, he’d talk to the earth. He taught me all the trees, berries, the birthing of animals. As Plains Cree, the horses were such a great part of our livelihood. We have that connection.

She shared that everyone had a responsibility in the family, and that at lunch time, everyone would be together. She was also taught that,

[e]verything had a spirit – the clouds, air, the wind, water, the wood, the animals. If the spirit is alive, they have their own language, and my father would talk to them in our Cree language, and they understood. I used to love how he would communicate with the horses and run around with them. We would try to imitate him.

As a little girl, after the rain, I would just run in my bare feet, with my dress flying around, right into the water and meet my father. I will always remember that most beautiful feeling of being connected to water.

Pauline has always loved learning, and this learning spirit was nourished by her family, by the land, as well as in school. When she was eight years old, she went to Blue Quills School, a residential school in St. Paul, Alberta, run by the Catholic Church and named after Chief Blue Quill (Sîpihtakanep) of Treaty 6 territory. Unlike so many, Pauline’s experience of school was positive. This was helped by her mother’s presence as the assistant cook at the school, allowing her a parental connection that most children were denied. As Pauline recounts: “They tried to make me a good Catholic girl, but I was traditional and I spoke my language. But I loved to learn. In grade 11 or 12, I went to school in Edmonton and I just loved it. I continued onto college for business school, and then I came to Toronto in the late 1960s with my three little ones. Going to Toronto was like going to China at that time!”

Compared to rural Alberta, Toronto meant a radical departure from a land-based lifestyle and a separation from a distinctively Indigenous community. Seeking community and family, Pauline became involved with the Native Canadian Centre of Toronto, known still as an important meeting place for the urban Indigenous community. Soon, Pauline connected to other Indigenous people, including the respected educators and leaders Jim Dumont, Edna Manitowabi, and Joe Hare. Becoming involved with the burgeoning Indigenous rights movement of the time, politics were braided into their new urban life.

Pauline and Vern became fixtures in activist circles, never shying away from the front lines of the causes they supported. In 1974, along with Louis Cameron (founder of the Ojibway Warrior Society of Kenora), Chief Ken Basil of the Bonaparte First Nations in British Columbia, and others, the two co-founded what would become known as the Native People’s Caravan.

“In 1974 there was a call out to organize the Native People’s Caravan. Vern and I organized, and we trucked 200-250 young people across the country with our Eagle Staff and developed the Native People’s Manifesto. Our main purpose was to go on September 30, 1974 to meet the parliamentarians, along with George Manual and the National Indian Brotherhood [now the Assembly of First Nations].”

The Caravan moved from Vancouver to Ottawa to deliver a manifesto to the federal government about the state of Indigenous lives, including poverty, dishonoured treaties, Métis rights, and other grievances. It became a symbol of Indigenous solidarity and self-determination, and education became a crucial focus, with the demand of “Indian Control of Indian Education.” As Pauline recounts:

We were so young, we said “enough is enough,” they are not listening to our chiefs, or our people. It was just broken promises, and then the White Paper In the caravan, we said we would go for the opening of the Parliament and talk to the parliamentarians about our education system, spirituality and health. It was a very peaceful thing.

When we got to Ottawa on Sept. 29, we had a peaceful protest, had the drum there, and the women took over. I was the last one to close the doors behind us, make sure nobody had any guns or sticks. We got there around 10 a.m. I remember my little boys were playing with their toys, and we made sure that if anything happened, the kids had someone to spirit them away. Then, of course, they sent the riot squad to us. It was really bloody.

We went back to this abandoned building [on Victoria Island], and called it the Native People’s Embassy. We had a big circle, sang songs, gave tobacco, and asked the spirit, “What now Spirit? They don’t want to listen to us, they beat us.” So many people were beat up and Vern was concussed, but we sat in that circle and looked at our manifesto, and decided that since the politicians would not listen to us, we would decide what we were going to do for ourselves. I put my hand up and I said, “I am going to put my mark on education. I am going to start my own school in Toronto.” That was October 1, 1974.

Though so many moments in Pauline’s life reveal it, perhaps October 1, 1974, marks the moment when the spirit of her great-grandfather from generations past became manifest. After her son Clayton’s refusal to return to school, she eventually established one in her own living room with her children and others, and with supporters who were conscientious of what was happening in the education system. Nobody was learning anything about Indigenous cultures.

Pauline’s school was modeled after The Red School House in St. Paul, Minnesota, as part of a project by the American Indian Movement. The founder of that school was her friend and AIM affiliate, Eddie Benton-Banai. As Sharon Berg recalls from her time living in the same housing co-op at Pauline in the early 1980s, Eddie had a big sticker across the back of his van that read, “You are in Indian country.” Sharon writes, “I couldn’t help but think this sticker was notice of Aboriginal resistance to the colonial land grab… It was also a resistance of the Residential Schools system. That note of resistance was the first seed for the establishment of Pauline’s school… That connection to the AIM Survival Schools is the second seed.”

Self-determination through Native education was a foundational, and at the time, radical idea of the Wandering Spirit Survival School. A “Native Way Education” for children was at the core of Pauline’s vision, grounded in a Four Seasons Curriculum, including language, ceremony, community immersion, and love. Obstacles to creating the school were many, and included voices from the Indigenous community. At first, Pauline paid for everything from her savings, but soon she found a critical circle of supporters who carried her vision forward:

The spirit of our ancestors and medicines helped us. I was well guarded. I knew lawyers and knew how I wished the school to be: To share the spirit of what our ancestors had been, passed on to our future generations.

We had people from all the four sacred colours involved. I always had people surrounding me and helping me out, women in particular. Vern helped in the beginning. Nora Keeshig-Tobias, Keith Lickers, and others helped us to create the curriculum. Everyone listened to my stories, and saw how my children were being treated in the mainstream school. There weren’t rich Anishinaabe to join us. We were an embarrassment at the time. People were scared of the child welfare system taking their children away if they got involved.

We called on the parents to be the advisors to us, so we developed a working parent’s council and they were just so lovely. I selected seven people, including Jim Dumont, to be on the council, and we became well known by the city as politicians. We had meetings at my house at that time with Keith Lickers [an elementary school teacher from Six Nations] and Al Bigwin [an elementary school principal who was First Nations] who both just listened and understood. I then registered with the Province, under my name, to continue the school as a private school.

Roger Obonsawin [Executive Director] approached me at the Native Canadian Centre, and he said “the board is offering you a classroom here.” We had this big classroom that was spacious and bright. Roger and the Centre helped us with funding and with their luncheon program. So, we moved to Spadina and Bloor.

Pauline believes that people eventually accepted her vision for a legitimate, Native Way school because they were accepting themselves and understanding why they were put on Turtle Island. Due to the success of the model established by Pauline and her large circle of supporters, in 1977 the Toronto Board of Education voted to accept it as an alternative school. She recalls the vote was not an easy win, and required Pauline to call on her great grandfather’s spirit.

After a few months at the Native Centre, the Toronto Board approached me to join as an alternative school. I remember it was a very emotional day for me. Dale Shuttleworth at the Board of Education stood by me, introduced me to everyone. I’ll never forget this one trustee who banged his shoe on the table, just like Khrushchev when he took his shoe off and banged it on the table at the UN. There was a lot of yelling, “Who do these Indians think they are?”

I had to leave the room when the trustees had to vote. I went out to another building and offered my tobacco, and I spoke to my grandpa: “Grampa, if you allow us to have our school as part of the TBE, we will still maintain our own way. I will not receive a red penny for seven years. Please help us.” That was a promise I made to the school. I also remember Irene Atkinson who was a hell raiser on the TBE, and a lot of my friends were there, and we won. We named the school Wandering Spirit, and it was the first legitimate Native controlled school across Canada.

Eight years after the school was accepted by the board, in 1985, a policy as passed by the TBE entitled, “Wandering Spirit: Self-determination through Native Education.” This bylaw aided in the proliferation of a Native Way Education through other public schools, including Eastview Jr. Public School, Riverdale Collegiate Institute, The Native Learning Centre, and The Native Learning Centre East.

As Pauline reminds me, near the end of our conversation, “Things change. Nothing is ever the same.” This isn’t a lament, but an acknowledgment of the shifting nature of the school. Pauline eventually had to withdraw from involvement in the school due to illness. In 1989, the name of the school was changed to the more generic name, First Nations School, and grew to be larger in scope but in some ways lost its ties to the original spirit of the school. Tanya Senk (Métis/Cree/Salteaux), who is currently the Principal, or Kiskitomowin eskwe (Knowledge woman), and the Centrally Assigned Board Lead in Indigenous Education within the Urban Indigenous Education Centre of the TDSB, called to let me know that in February, 2019, the school had a reclaiming of the name ceremony. Tanya shared that the re-named Kapapamahchakwew – Wandering Spirit School, has grown from a K-8 to a K-12 school, and is now located at 16 Phin Avenue, in the old Eastern Commerce School. The academic year 2021-2022 marks the first time that Grade 12 will be offered.

“Education in this school is about knowing who you are as an Indigenous person, and also thinking about Indigenous futurity, and what it means to be an Indigenous person in the 21st Century,” says Tanya. “Knowing who you are, and being creative and innovative in your thinking.” She mentions that the aim of education to her is about “finding your gifts and then sharing your gifts,” and she centers an approach to teaching developed by Mi’kmaq Elder Albert Marshall called “Two-Eyed Seeing.”

In essence, Two-Eyed Seeing is about braiding together the best of Indigenous knowledge with knowledge from other cultures. As Albert Marshall shared in a talk about this concept at Humber College, “There is no hierarchy of knowledge. We all hold a piece of the puzzle.” As it was always part of Pauline’s intention to include the four sacred colours, today’s Wandering Spirit School invites learners from any cultural background who seek an Indigenous-focused education.

Pauline’s vision circles back to her ancestor, Kapapamahchakwew, and is carried on through her children, through the people she has taught, and through Wandering Spirit School. Her vision reminds us that, even though this city defines our lives in countless ways, there is still a way of finding the gifts that our ancestors fought for, and an importance to carrying them forward: “You have to know your creation story. That is where we get our curriculum from, and our songs, and our stories. That’s where the spirit comes from. The children who attended never knew their spiritual names or clan systems, and we taught them that. That whole spirituality was embedded in them, and we helped them bring it out. We were just spiritual helpers, and that’s all I’ll ever be.”

(Source information from The Name Unspoken: Wandering Spirit Survival School (2019) and personal correspondence with author Sharon Berg.)

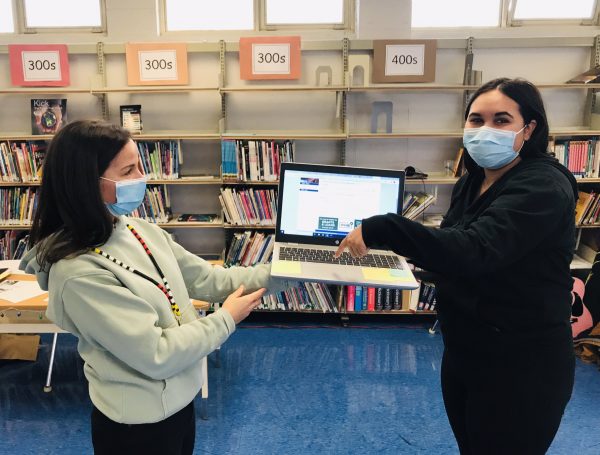

top photo courtesy of the Wandering Spirit School’s Twitter account @KWSS_TDSB