Almost lost in Toronto’s vault of Black history is a case of racial discrimination in the spring of 1964 that nearly prevented the Bloor subway line from opening on time.

In mid April of that year, Jack White, a 38-year-old Black ironworker and union steward, was laid off from his job as part of the subway construction crew working under the Prince Edward Viaduct, the iconic, 105-year-old truss arch bridge that spans the Don Valley. His union asserted that White was dismissed because of his colour. His co-workers set down their tools alongside his and a protest ensued for the next two-and-a-half weeks, threatening the project’s timely completion and a delay to the official opening. McNamara, the offending company, sub-contracted the job to rival Dominion Bridge rather than re-hire White.

Two-and-a-half weeks later, White did return to the bridge. “Dispute Settled,” crowed the headline of an undated newspaper clipping in the family’s scrapbook, which noted that White’s return had “averted a complete stoppage of construction of the Bloor-Danforth subway.”

Castle Frank Station opened on time along with the rest of the first phase of today’s “Line 2” on February 26, 1966.

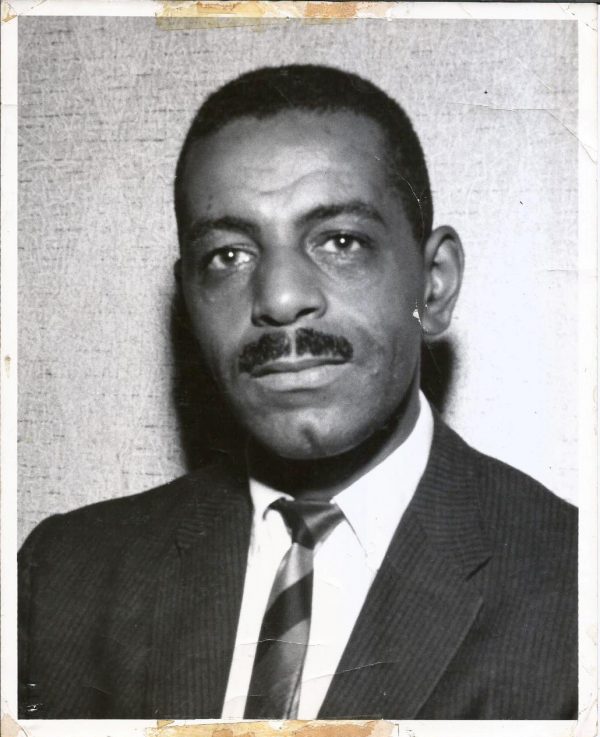

Who was Jack White?

He was a hardworking family man living in the home that he and his wife, Alma Dixon, had purchased in 1957 at Dupont and Ossington. A transplanted Nova Scotian with a rich family pedigree, John Edgar (Jack) White was born in Halifax on July 10, 1925. He was 12 when his father, a renowned minister who is federally recognized as a significant historical figure, died. His mother, Izie Dora, was musically gifted and had married Capt. Rev. William Andrew White at age 16. Due to his father’s death in 1936, Jack, like all the boys in the family of ten, was forced to quit school and go to work to support the family. He left school with a Grade 5 education and upgraded himself taking night courses.

Jack took basic training in the Canadian Army, though he did not serve in the Second World War because he had been discharged for medical reasons. In Halifax, Jack worked for CN. That job didn’t last very long, but it was that position that introduced him to the union movement.

It was a quick initiation, as Jack told it:

“I had just come out the army. UIC [the Unemployment Insurance Commission] gave me a slip to report to Canadian National Railroad. The superintendent said, ‘We have no job.’ Then he looked and he said, ‘Wait. Are you related to Reverend White?’ And I said, ‘Yes. He’s my father.’ ‘Oh well,’ he said, ‘that’s different’ and he gave me the job.”

Jack continued: “I took the job two days before a pending strike. I knew nothing about strikes. Nobody was telling us anything. So I wrote to the president of the union saying, ‘What the hell is happening here?! I’m a new employee and somebody tells me I may go on strike.’ Before I knew it someone said, ‘Well, you should be our representative.’ So I became the shop steward in the car department. There were porters … but no Black had ever worked in the car department before.”

Jack always made sure he was impeccably dressed. He never wore jeans or shorts. He was not a sportsman, nor a hobbyist – he was a worker’s man and a private, family man.

He and Alma moved to Toronto in November, 1949, and eventually had four children.

He worked in the construction industry, always edited his union’s newsletters, and was editor of “The Canadian Negro,” a landmark newspaper in the early 1950s, for four years.

Those who knew Jack remember his gorgeous singing voice, a trademark of his musical family whose most-acclaimed member was his international concert-singing sister, Portia White. If old enough, they’d also remember Lorne White, a regular on CBC’s long-running, weekly television show, Singalong Jubilee. Jack’s accomplished older brother Bill received a 1970 Order of Canada medal for humanitarianism, was decorated many times for his community service and lauded for his remarkable musical ability. Jack himself sang for a time with the Toronto Jewish Folk Choir.

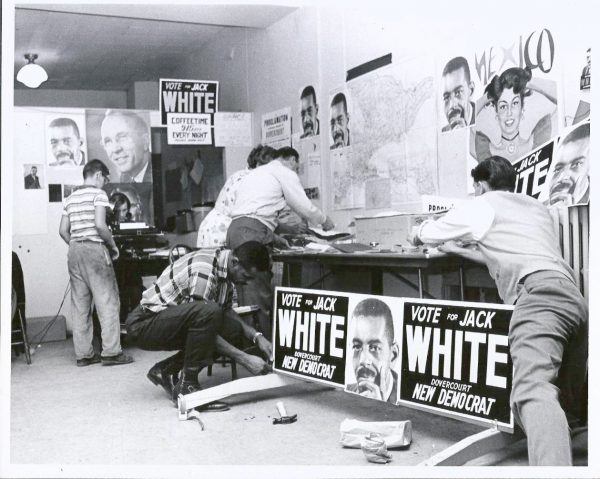

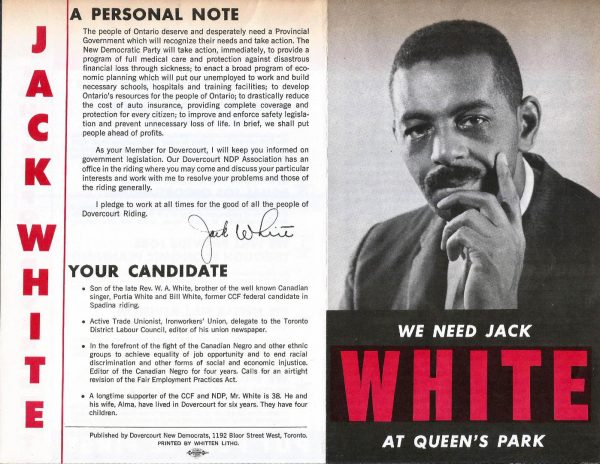

He earned the nickname, “Jack White the Black Red,” because he was a member of the Communist party for a time. In 1963, he ran as a provincial election candidate for the New Democratic Party in the Dovercourt riding — not expecting to win, but feeling it was important to make a statement as a standard bearer. His son, Allan, recalls driving around with Jack on a rented flatbed truck, his father soliciting votes through a megaphone. One of Jack’s prized possessions was the photo album dated September 25, 1963, from campaign workers. He was one of the first Black people to run for provincial office. Another, Leonard Braithwaite in Etobicoke, was the first in Ontario to be elected MPP in that same year.

Jack became the first Black business representative of any union in North America for the Ironworkers. In the 1970s, he was director of social services for the Ontario Federation of Labour and a business representative for CUPE. His accomplishments were door-opening for others. Jack didn’t think the unions of the day were moving quickly enough in embracing diversity. He was a pivotal figure in the Ontario Black Trade Unionists organization, which named a scholarship after him.

Measured and controlled, Jack’s passion emerged when he was fighting for rights and freedoms, whether outside the American embassy on University Avenue, picketing for “Negro freedom” in the 1960s, or at an arbitration hearing for a sick or injured worker.

After he left CUPE, Jack became an industrial relations consultant, who resolved hundreds of files and counted many unions among his clients. He established a stellar record successfully fighting for workers’ benefits and entitlements — a trusted and able confidante and claims negotiator with an unbeatable North American reputation.

Jack White died on Sept. 10, 2002. When commuters ride 494 metres across the Bloor Viaduct, some 40 metres above the Don Valley Parkway on Line 2, they are passing the spot where an historic union battle was launched to protect the rights of all Black workers.

There ought to be a heritage marker installed at that point, to commemorate the Jack White story and labour’s significance in that fight against systemic anti-Black racism. For more on Jack White, visit the Toronto Workers History Project page at twhp.ca.

Sheila White, a niece of Jack White, is a writer, speaker and Unitarian lay chaplain. Her race relations-themed novel, “The Letters,” is due for release by Yorkland Publishing later this year.

images courtesy of the White family

5 comments

Remarkable story about an incredible man. Thank you for sharing

These are the stories that should be in our history books, not only in articles in 2023.

Wonderful history! I loved the nickname “Jack White the Black Red.”

A wonderful history! I too, after being a union rep for most of my career, well understand how strong the opposition can be to doing the right thing… but happily this didn’t stop Jack! Bravo Sheila! A wonderful read!

Remarkable history! The things that we take for granted in current times… Yes, this should be part of Canadian history books because it IS Canadian history! Good work, Sheila!