“There are times when city dwellers have been roused from passivity – Disaster (Ground Zero) and personal affront (NIMBYism) make protesters out of us all, but we are rarely roused from the day-to-day, brick-by-brick additions that have the most power to change our environment. We know what we already like but not how to describe it, or change it, or how to change our minds. We need to learn how to read a building, an urban plan, and a developer’s rendering, and to see where critique might make a difference.”

– from the book’s Introduction

Edited by Alexandra Lange – Princeton Architectural Press (2012)

As the eleventh book in the Princeton Architectural Press Architectural Brief series—a series which includes a broad range of topics ranging from ethics to lighting to model making—Writing About Architecture by Alexandra Lange does not disappoint. For anyone who has enjoyed the prose of Jane Jacobs, Ada Louise Huxtable, or Michael Sorkin, this is a book for you. For not only does Lange skillfully bring together some choice writing from the aforementioned critics, she also interweaves her own interpretation of these great architectural orators, and what we can learn from them in an accessible way that the layperson can easily understand. It is a laudable aspiration, certainly as the planet now has more than half of its population living in cities.

Both an architecture critic and professor at NYU, Lange builds upon the legacy of a long line of great architectural writers, having distilled their methods of architectural dialectic to disseminate to her students. As such, she groups them into four camps: the formal, the experiential, the historical, and the activist. Critics who favour the walk-through descriptive style like Lewis Mumford and Ada-Louis Huxtable fall into the first camp, with former NY Times critic Herbert Muschamp representing the experiential camp (the latter’s review of the Guggenheim gallery in Bilbao is the subject of the book’s second chapter). Into the historical camp Lange places present-day New Yorker architecture critic Paul Goldberger, whose style tends to give more context to his subject than other writers, while lastly into the activist camp Lange places Michael Sorkin and Jane Jacobs.

In the book’s first chapter “Skyscrapers as Superlatives”, Lange uses Mumford’s 1952 critique of the Lever House as a point of departure, humourously pointing out how architecture criticism has now been reduced to an exercise in superlatives: the tallest, the greenest, etc. In the same chapter she also cites Louis Sullivan’s 1896 essay “The Tall Office Building Artistically Considered”—from which we get his famous quote “Form ever follows function”—pointing out that Sullivan was writing for architects in order that they not pollute the cityscape with bulky blocks of real estate. Ironically, he points out how in his time skyscrapers weren’t designed by architects, but instead by the developers, city planners, and engineers, and so it was his ambition that his essay could change this situation.

Lewis Mumford’s essay on the Lever House meanwhile, written about a half century later, is from the point of view of the man on the street, and as such does not consider the architecture as real estate so much as an orchestration of materials and space to create a meaningful contribution to the public realm. What is most remarkable about Mumford’s writing is that there were never any photographs accompanying his reviews, and hence his formal, descriptive style.

Lange further points out that what is most remarkable about Sullivan’s writing is that he was also a practicing architect, and like his protégé Frank Lloyd Wright, would create some of the most significant prose on architecture written since Palladio. His description of a tall office tower with its natural divisions of base, floors, and penthouse has been the template for both modern architectural writers and practitioners ever since. Lange closes out the chapter juxtaposing Sullivan and Mumford’s writing style with Paul Goldberger and his 2006 review of Norman Foster’s Hearst Tower in NYC.

The book’s second essay, “What Should a Museum Be?” (named for a 1960 essay by Huxtable with the same name), looks at Herbert Muschamp’s 1997 review of the then new Guggenheim gallery in Bilbao, Spain. A highpoint of the book to be sure, Muschamp as a personal friend of the architect’s was not only able to interview Gehry in his Santa Monica office, but actually visited the museum with him as well. His descriptions are, as Lange points out, freely associative, likening the building in one moment to Marilyn Monroe, and next comparing the titanium cladding of the gallery to the dull side of a piece of tinfoil, its appearance ever-changing with the reflection of the clouds and sun in the sky:

“It’s a bird, it’s a plane, it’s Superman. It’s a ship, it’s an artichoke, the miracle of the rose. A first glimpse of the building tells you that the second glimpse is going to be different from the first. A second glimpse tells you that a third is going to be different still. If there is an order to this architecture, it is not one that can be predicted from one or two visual slices of its precisely calculated free-form geometry. But the building’s freedom of spirit is hard to miss.”

Lange points out that as architecture critic for the New York Times from 1992 to 2004, his often emotionally charged style was a marked contrast to the laudatory architect-as-master-builder approach of his predecessor, Paul Goldberger. Muschamp would use pop-references – popular music, comic books, movies – all to characterize his architectural descriptions, and his review of Bilbao is no less flamboyant. As Lange describes his writing style, “there is a picture in his head of the building, and he is using any means necessary to communicate that to his reader.” Muschamp’s description of the pilgrimage to the building beginning at the Bilbao airport is no less prescient, and an experience I can personally relate to, having visited Bilbao three years ago and traveling by cab directly to the gallery from the airport. In order to get the full Bilbao Effect, it would seem one needs to be an architectural tourist. The difference with Muschamp was he was writing his review a full year before another critic, Witold Rybcynski, would coin the now overused term.

The remaining four essays in the book look at architectural writing in terms of the landscape and the city, rather than directly at the subject building itself. Michael Sorkin’s short essay, “Save the Whitney,” which he wrote for the Village Voice in 1985, (and which was also featured in his excellent book Exquisite Corpse) is a short and sweet example of architectural preservationism at its best, where the pen can indeed prove mightier than the sword. Next is Charles Moore‘s writing on civic monuments entitled “You Have to Pay for the Public Life,'” subject of Lange’s evocative essay “Searching for a Center.” This is followed by an 1870 essay by Frederick Law Olmsted on the importance of public parks, which Lange makes the subject of her whimsically titled essay “Landscape is More than a Lawn”. But the best is saved for last, with a segment of Jane Jacob’s Death and Life of Great American Cities being the subject of the last chapter in the book – “Criticism from the Ground Up.”

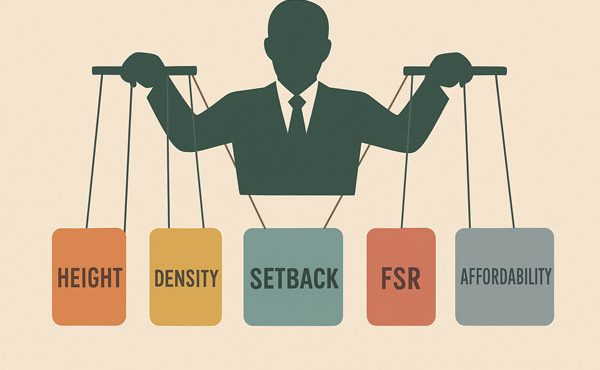

As our present age continues its paradigm shift to a Do-it-Yourself culture, Lange’s ambition is honourable: that we all learn, both architects and non-architects alike, to see and understand our built world, especially as more and more of us continue to gravitate towards the city (and more and more of us continue to blog about it). As the digital age of Zuckerberg continues to make redundant the analog age of Gutenberg, so is it vital that this new blogosphere be urbanisticaly literate, able to engage in a meaningful discussion about our built environment whether to discuss zoning bylaws or heritage structures.

Writing About Architecture is another thoughtful publication by Princeton Architectural Press in their Architecture Brief series and for those ‘with eyes that do not see’—to borrow the expression from another great architect and writer. As for Lange, now teaching architectural criticism at NYU for five years now, she offers in Chapter Two some of her best advice on architectural writing, perhaps inspired by Muschamp’s irreverent literary celebration of the Guggenheim at Bilbao:

“The lesson for the writer is to let the imagination run wild, even if you end up editing out any over zealous material. The critic can use any means necessary to describe what he/she sees, and sometimes turning to a pop image or personality may be the easiest, and most effective, path. Architecture is not hermetic. Metaphor and association outside the world of buildings can help let others in on what we feel when we are in architecture. A critic only has words, and the world of extra-visual association offers additional colour to the palette.”

***

For more information on the book, visit the Princeton Architectural Press website.

**

Sean Ruthen is a Vancouver-based architect and writer.