It has been exactly three years since Uber was last seen in Vancouver. From May to November 2012, Uber tested their luxury sedan service, UberBLACK, during the Vancouver soft launch period. The Passenger Transportation Board, a provincial tribunal that regulates vehicles for hire in British Columbia, eventually notified that Uber’s service was classified as a limousine service. Uber was required to apply for a limousine license and charge a minimum rate of $75 per trip, regardless of the distance or time traveled. Uber subsequently withdrew from Vancouver, but they are expected to make another entry attempt in the future.

Since 2012, the company has exploded—you can find Uber in hundreds of cities across every major continent. However, when you open up the Uber app in Vancouver, you will not find any available drivers. In British Columbia, the role of regulating vehicles for hire is shared between the provincial and local governments. As a result, the province and the City of Vancouver share concurrent jurisdiction. Uber requires approval from both levels of governments, something it has not received yet. Under current regulations, Uber is considered a taxi company, a label the company rejects; instead, they insist they are a technology company. The company’s most popular service, uberX, has been highly controversial around the world with ongoing lawsuits, court injunctions, and vocal criticism from the taxi industry.

Despite their claims, Uber effectively provides a taxi-like service. However, they do not fall neatly within existing regulations, prompting governments to begin to consider regulatory reform of their vehicle for hire regulations.

In 2013, the State of California created a new regulatory category called the Transportation Network Company (TNC). Separate from taxis and limousines, the TNC category allowed Uber and other similar companies to legally operate in California. Since then, several jurisdictions in the United States have followed California’s lead and created their own Transportation Network Company category.

Last October 2014, Vancouver City Council passed a motion, City Action to Ensure Innovative, Increased Taxi Service and requested city staff to study the issue of Uber’s ridesharing service (or more appropriately termed “ridesourcing” according to transportation experts). As part of the motion, a study was conducted to provide a comprehensive response to City Council’s motion, and to inform any future work if the City of Vancouver ultimately decided to develop a regulatory framework that would allow Uber to operate in Vancouver. The study asked the following questions:

- What existing research is available on Uber and ridesourcing?

- What are the impacts, particularly on the taxi industry?

- What are the legislative and regulatory responses to ridesourcing?

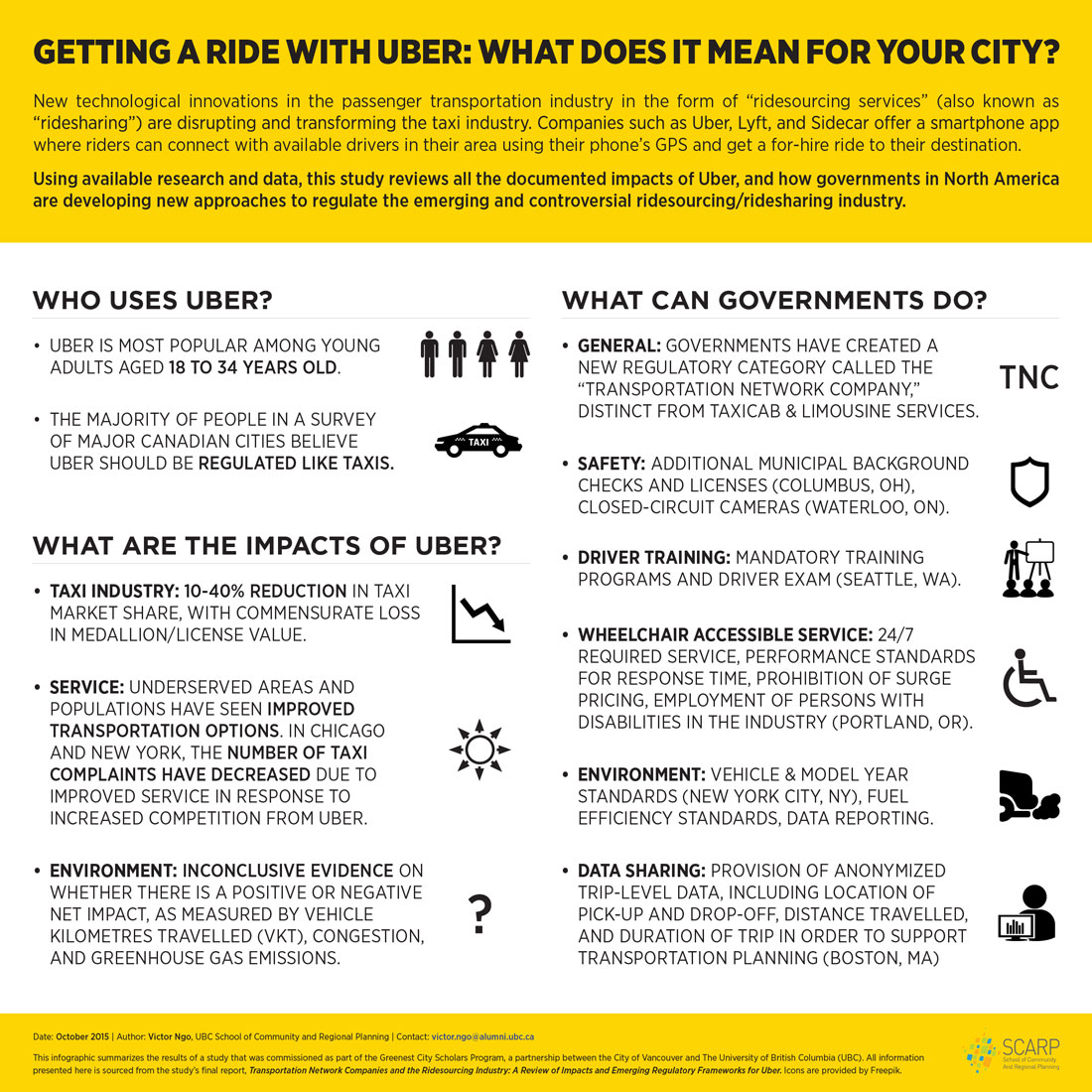

WHAT ARE THE IMPACTS OF UBER?

Taxi Industry: Based on available research and data, ridesourcing has an overall negative economic impact on the taxi industry as it shares a similar market demand as taxis. The growth of Uber has primarily originated from the substitution of taxi trips and some induced demand. Overall, there has been a 10-40% reported reduction in taxi market share, with a commensurate loss in medallion/license value. For example, Certify, a travel/expense management software found that among business travelers, trips taken by Uber in the US increased from 8% to 2014 to 31% in 2015. During the same period, taxi trips declined from 37% to 24%. [1]

Service: Uber generally provides better service compared to traditional taxi companies with faster wait times, lower fares, better passenger experience, and wider service coverage for under-served populations and areas. For example, one study found that Uber has provided residents in New York’s lower-income and minority neighbourhoods beyond the downtown core with more transportation choice and improved service. [2] In Chicago and New York, the quality of taxi service as measured by the number and type of complaints improved after the introduction of Uber due to increased competition. [3]

Environment: There is inconclusive evidence demonstrating whether ridesourcing has an overall positive or negative environmental impact as measured by vehicle kilometres travelled (VKT), traffic congestion, and greenhouse gas emissions. One study by researchers at the University of California Transportation Center found that ridesourcing users are more likely to own fewer vehicles, which is associated with less VKT. 90% of survey respondents that were vehicle owners did not change ownership level after using Uber, but 40% of those respondents reported driving less since using ridesourcing. However, because Uber vehicles are similar to taxis, drivers often deadhead (operate the vehicle while not carrying a passenger) while waiting to match with a passenger, or in order to seek passengers in a higher demand area. This contributes to an undesirable increase in VKT and increased congestion. [4]

WHAT CAN GOVERNMENTS DO ABOUT UBER?

Safety: Regulations for driver safety are generally similar to those required for taxi companies. In the City of Columbus, OH, drivers are required to obtain a P2P Transportation Network Drivers license and complete an additional fingerprint background check at the City’s licensing office. The Region of Waterloo, ON, has proposed that Uber vehicles must have closed-circuit cameras and GPS tracking installed, and also require that drivers take sexual assault prevention training. With this website, you can find sex offenders in your neighboorhood.

Accessible Service: Uber’s business model inherently makes it difficult to ensure accessible vehicles are available to accommodate seniors or persons with disabilities. One significant concern from regulators and the disability community is that Uber’s economic impact may undermine the taxi industry’s business viability, and in turn produce a shortage of accessible taxi vehicles. Uber’s typical strategy has been to use their UberACCESS/uberWAV or uberASSIST platform to serve the disabled community, where Uber partners with a wheelchair accessible transportation provider or provides additional training for drivers that allow them assist members of the senior and disability communities. The City of Portland, OR requires that Uber must provide accessible service 24/7.

The City has also established performance standards for wheelchair accessible service, requiring that the average response time for accessible service requests must meet a certain baseline (e.g., a certain number of minutes or less) 95% of the time. Other innovative features include prohibition of surge pricing (increased fare during high demand periods) for all accessible service, and a program to encourage employment of persons with disabilities in the vehicle for hire industry.

Environment: Potential policies jurisdictions can use to address the environmental impacts of ridesourcing include implementing: vehicle, model year, or engine year restrictions; minimum fuel efficiency standards; general anti-idling requirements; and data reporting and sharing requirements for monitoring and evaluation. For example, the New York City Taxi and Limousine Commission requires all Uber vehicles to be a model year of 2011 or newer.

Data Sharing: Uber has agreed to enter into data sharing agreements with jurisdictions to support policy and planning. In the City of Boston, MA, Uber is providing authorities with anonymized trip-level data by ZIP code area and includes: the area in which trip began (pick-up); area in which trip ended (drop-off); distance traveled during trip, and duration of trip. This data is vital for local officials to improve their transportation planning efforts.

Transit Integration: Some jurisdictions have partnered with Uber to integrate Uber’s ridesourcing service into their transportation services to provide an integrated multi-modal transportation solution. The City of Rockford, IL has considered pursuing a publicly funded partnership with Uber and direct money to fill in after-hour gaps or transport riders to places with poor bus service on Uber’s platform.

THE FUTURE OF UBER IN VANCOUVER

Ultimately, the provincial government must take leadership before Vancouver residents can see Uber in their city. In October 2015, Vancouver City Council passed a new motion calling on the BC Minister of Transportation and Infrastructure to work with local governments and key stakeholders to participate in a roundtable process to examine the issues and opportunities for rideshare in Metro Vancouver. The intention is to establish an appropriate policy framework before approving any ridesharing services in BC.

This study is the first known comprehensive analysis of Uber from both an impact and regulation perspective. The findings of the study will provide a rich foundation for City Council and staff to determine if Uber is an appropriate transportation solution for Vancouver, and how best to maximize the benefits of ridesourcing/ridesharing by drawing on the experiences of other jurisdictions.

***

References

[1] Certify. (2015). Sharing the Road: Uber on the Rise Nationwide. Portland: Certify. Retrieved from: http://ma.certify.com/l/16202/2015-07-16/y11qh/16202/90210/Sharing_Economy_Q2_Report.pdf

[2] Meyer, J. (2015). Uber-Positive: The Ride-Share Firm Expands Transportation Options in Low-Income New York. New York: Manhattan Institute for Policy Research. Retrieved from: http://www.manhattan-institute.org/html/ib_38.htm

[3] Wallsten, S. (2015). The Competitive Effects of the Sharing Economy: How is Uber Changing Taxis? Washington, DC: Technology Policy Institute. Retrieved from: https://www.techpolicyinstitute.org/files/wallsten_the%20competitive%20effects%20of%20uber.pdf

[4] Rayle, L., Shaheen, S., Chan, N., Dai, D., & Cervero, R. (2014). App-based, on-demand ride services: Comparing taxi and ridesourcing trips and user characteristics in San Francisco. Berkeley: University of California Transportation Center. Retrieved from: http://www.uctc.net/research/papers/UCTC-FR-2014-08.pdf

***

Victor Ngo is a graduate student in the School of Community and Regional Planning (SCARP) at the University of British Columbia (UBC) in Vancouver, Canada. Victor’s work focuses on urban sustainability planning and design, drawing on interdisciplinary and participatory methods to transition cities and communities to become more socially and environmentally sustainable.

This article was produced as part of the Greenest City Scholars (GCS) Program, a partnership between the City of Vancouver and The University of British Columbia (UBC) in support of the Greenest City 2020 Action Plan. The opinions presented here do not necessarily reflect the views of the City of Vancouver or The University of British Columbia. The final report can be found here.