By Annika Airas and Trevor Wideman

Vancouver’s waterfront has undergone rapid transformations over the past decades, following a global movement that has seen industrial sites in central urban locations give way to residential and commercial development. For example, after the original Squamish, Musqueam, and Tseil-Waututh inhabitants were displaced, False Creek, Coal Harbour, and the numerous other water bodies that surround the city became lined with sawmills, shipyards, and other industries, whereas they now contain recreational spaces and high-end glass towers.

As is blatantly clear upon strolling along Vancouver’s Seawall, there is very little material evidence left of the (pre)industrial past, and very few indicators as to who used to live and work on the waterfront. However, recently there has been a growing interest in making the waterfront more engaging and easily accessible for users, particularly through the use of creative public spaces.

The built environment reflects the types of activities that people want to engage in, and recently, a new proposal for the Vancouver waterfront has taken shape in the form of a seawater pool and a public space. This space, known as the Harbour Deck, has been suggested for Coal Harbour by HCMA Architecture + Design—the firm responsible for various well-known aquatic facilities in the region, including Vancouver’s Hillcrest Centre.

With no funding or official backing for the proposal, Harbour Deck was created to start a wider public discussion on how we can better use our waterfront. It was included in the Museum of Vancouver’s Your Future Home: Creating the New Vancouver exhibition that recently ended. Yet, despite the latter, the project is worth critical reflection.

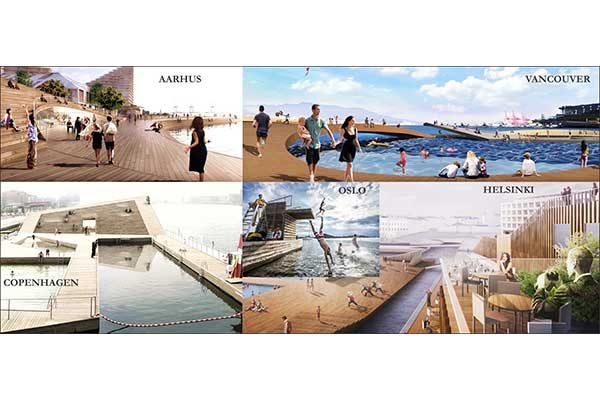

Harbour Deck takes its inspiration from waterfront districts in Nordic cities such as Copenhagen, Denmark and Oslo, Norway. A similar project is being built in Helsinki, Finland, where a new public seawater pool is opening up in the summer of 2016.

Presently, the waterfront on Coal Harbour is primarily used as a viewpoint for the public and it is difficult to access otherwise. Drawing on Nordic examples that have used stylish and playful urban architecture to create hip and cool public spaces, the Harbour Deck pool remodeling service aims to promote healthy activities in a trendy environment, while encouraging users to access the water. Indeed, the harbour pools in Copenhagen are touted as some of the trendiest spots in the entire city. Similarly, the Harbour Deck aims to provide a tourist-friendly public space for the Coal Harbour area.

However, even though the proposals for these public spaces share similarities in design, scale, location in the city, and building materials, their cultural contexts are quite different. For example, Helsinki (among other Finnish waterfront cities) has a long history of public baths and saunas, so their new plans have a link to a local cultural heritage that has never really gone away. While it could be argued that Vancouver’s waterfront was historically more easily accessible to the public, there has been a long-term lack of engagement with the water due to the ongoing development of exclusive luxury condominiums and commercial activities. In contrast, the Vancouver Harbour Deck design represents a new approach that promotes a different type of engagement with the waterfront.

The Harbour Deck proposal draws on development ideas that have been viewed as successful in the Nordic context and have been touted for their world class appeal, allowing such ideas to be introduced to Vancouver. Such ideas have the potential to become “politically powerful”1 and, over time, influence the built form and use of the waterfront. Yet, an important question remains: are we actually modifying these city districts to become more homogeneous?

First, the activities and designs that are promoted in such plans bear a striking resemblance to one another, typically making cities and districts across the globe increasingly monotonous. Second, such plans also overlook the local history and heritage of particular areas. Similarly, proposals such as these are often sold with ideas that make them more attractive for businesses and tourists alike, and thus, the land uses and business activities that follow such plans (i.e. restaurants, bars, and other commercial uses) often disregard what is truly unique about such sites.

Clearly, a waterfront development idea such as the Harbour Deck gains traction by promoting trendy and healthy waterfront development ideas already in use in different cities across Europe. However, such plans are created simply to appeal to a certain segment of the public. By drawing strong inspiration from waterfront planning ideas seen elsewhere, we downplay the diverse local histories and activities that existed on Coal Harbour and ignore the unique social context of the development site. This, in turn, limits our ability to make public spaces that truly reflect Vancouver.

***

FOOTNOTE:

- Cristina Temenos and Eugene McCann, “The Local Politics of Policy Mobility: Learning, Persuasion, and the Production of a Municipal Sustainability Fix,”Environment and Planning A 44, no. 6 (2012): 1389–1406.

**

Collage Source Images:

HELSINKI: http://www.helsinkiallas.fi/joukkorahoitus/

VANCOUVER: http://www.vancitybuzz.com/2016/01/massive-outdoor-swimming-deck-proposed-for-coal-harbour/

COPENHAGEN: http://www.vinterbadbryggen.com/page/english

AARHUS: http://archpaper.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/big-bjarke-ingels-group-aarhus-island-basin-7-denmark-designboom-03.jpg

OSLO: http://1.vgc.no/drpublish/images/article/2015/08/21/23509530/1/fullbredde/2428130.jpg

**

Annika Airas recently completed her PhD at the University of Helsinki (Finland) and was a visiting scholar in Canada at Simon Fraser University. Her research focuses on changes in the built environment of urban waterfronts.

Trevor Wideman is a PhD student in Geography at Simon Fraser University and a Research Assistant with the Landscapes of Injustice research project at the University of Victoria. He lives, works and studies in Vancouver.