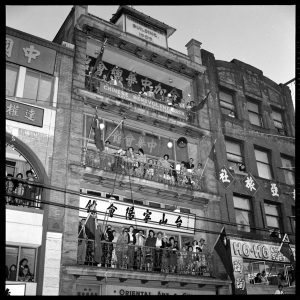

In 2014, the City of Vancouver announced a three-year, $2.5 million grant program to provide critical upgrades to Chinatown’s historic clan and society buildings. At the time, critics warned that while the funds would maintain the physical buildings, the neighbourhood was still under threat by accelerated gentrification. Then last year, the National Trust for Canada featured Vancouver’s Chinatown on its annual list of Top 10 Endangered Places. The charity blamed “relentless development,” warning that “without better control on new development and efforts to sustain local businesses, Chinatown’s unique character will be lost.”

Civic historian John Atkin agrees. “It’s easy to look at the society buildings and say, ‘Wow, we’ve saved Pender Street. Done.’ But if you lose the vegetable shops and the barbecue shops, then you don’t have a living neighbourhood. Pender Street would become a petting zoo for society buildings, but you have nothing else.”

On Thursday April 27, Atkin and Senior Planner for the Downtown Eastside Tom Wanklin will speak about Chinatown’s clan and association buildings and how the societies they housed helped Chinatown survive and prosper in the face of discrimination, disenfranchisement and threats of urban renewal. Built in an era when mutual support was necessary for the city’s Chinese immigrants, clan and benevolent societies provided housing, fast payday loans and other social supports to a tight-knit bachelor community. They also helped settle disputes and oversaw the return of remains to China when somebody died. Today, the societies have evolved into social clubs and guardians of community heritage, says Atkin, who co-wrote Chinatown’s National Historic Site District application, and is currently President of the Chinese Canadian Historical Society. In time, Atkin hopes they could periodically host open houses to share their histories with the public.

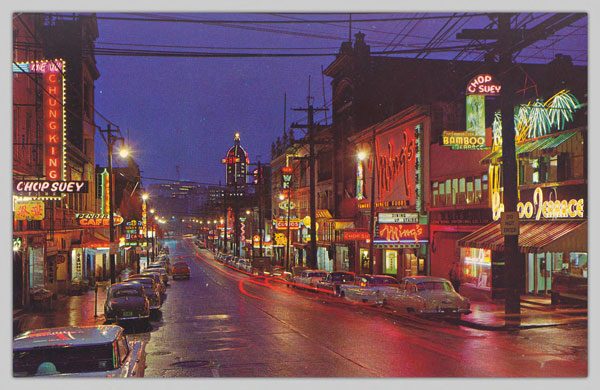

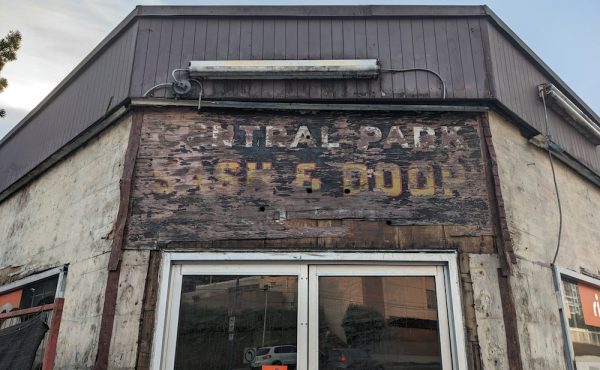

But he emphasizes that if Chinatown is to survive as a cultural landscape, the neighbourhood needs breathing space to transition and policies to retain existing retail, including the longstanding shops and eateries that established Chinatown residents rely on. “No one is saying Chinatown can’t change and can’t evolve, because Chinatown today is vastly different from Chinatown in the 1970s, which is vastly different from Chinatown in the 1950s, which was light years away from Chinatown in the 1930s. But if you set in motion a rate of change that doesn’t allow for the evolution, then you stand to wipe it out – and you don’t get it back.”

More than half of local food businesses like green grocers, fishmongers, and butchers have closed in the past six years, according to a study by the Hua Foundation. Atkin acknowledges that a big challenge comes from within; longstanding family businesses are closing in Chinatowns around North America, because shopkeepers are retiring and their children aren’t interested in taking over.

But he also points to encouraging signs of revitalization. “It takes a couple of generations for folks to get re-involved,” he notes. “We’re seeing a younger generation take an interest in societies and in making sure that they don’t disappear.” Chinatown is also proving to be a draw for some third-generation Chinese entrepreneurs like Ryan Mah, the great-grandson of famous B.C. grocery store businessman H. Y. Louie. Mah, opened a Hawaiian poké restaurant on Main and Keefer last December, and is part of a recent wave of businesses injecting new life into the neighbourhood.

“Anyone who thinks we’ll get Chinatown of the 1970s back?” says Atkin. “No. But if I can walk up the street and go to Dollar Meats, go to Ho Ho, and buy broccoli in the neighbourhood, then Chinatown survives.”

***

John Atkin and Tom Wanklin‘s talk on Vancouver’s Chinatown takes place this Thursday April 27 at 7:30pm at the Museum of Vancouver (1100 Chestnut Street). Part of the Vancouver Historical Society speaker series, the talk is by free for members, or by donation. Everyone is welcome to attend.

***

Madeleine de Trenqualye is a historical researcher and writer who has worked for Parks Canada, the National Historic Sites and Monuments Board and multiple heritage institutions.