Vancouver’s Chinatown is one of the city’s oldest neighbourhoods. Initially it developed as a segregated enclave along Carrall and Pender Street (then Dupont Street until 1904) for the Chinese labourers who first settled in the 1880s (Donald Luxton and Associates Inc. March 2016). Since its formation, Chinatown has been part of the Downtown Eastside that is reputable for being Canada’s “poorest postal code“. Chinatown itself consists of two zones: one is heritage-designated HA-1 along Pender Street and adjacent to the already gentrified Gastown. Chinatown South HA-1A is not heritage designated and is situated south of Pender Street, including Main Street and Keefer Street.

Compared to Vancouver’s downtown peninsula, land is still affordable and many buildings are century-old—some deteriorated—which creates profitable potential for developers to reinvestment. This causes polarizing dynamics between the local community who want to preserve Chinatown as it is and developers who want to invest in real estate and transform the neighbourhood. In this sense, Chinatown is at the crossroads between preserving its cultural heritage – both tangible and intangible—or becoming an attractive neighbourhood for an emerging, middle-class young-professional demographics. Spacing Vancouver’s Ulduz Maschaykh had the opportunity to individually interview prominent Real Estate Marketer and Art Collector Bob Rennie, Vancouver Civic Historian John Atkin and former United Nations Special Rapporteur for Housing Miloon Kothari. The interviews here are compiled with the aim of highlighting the complex relationship between heritage preservation, gentrification and affordable housing.

Spacing: Everyone is talking about how Vancouver’s Chinatown is changing in the 21st century. Especially along Main Street, many old businesses are closing, while new ones open. What is gentrification to you? How does it happen? And is Vancouver’s Chinatown being gentrified?

BR: The topic is soooo complicated and there is no paragraph that can catch its complexities. I have a say, however, that a general saying that applies to any city in the world: Follow the artists and the prostitutes, and I will show you where the city is moving towards! As both the artists and the prostitutes want to be as close to the energy centre of a city as possible, for as cheap as possible. This concept works in any city in the world, and as art plays a pivotal role in making cities vibrant, should we seek to eliminate students and artists then? I see a lack of diversity as a sign of gentrification—when there is no diversity of people in a neighbourhood and when social housing disappears. Another sign of gentrification is when there is no diversity of race and income.

Whether Chinatown is gentrified is a matter of perception. If you lived in Vancouver all your life, you would look at Gastown and Chinatown as questionable and forgotten places. But if you lived in any of the other major cities in the world, you will look at Gastown and Chinatown as places that have emerging and diversified communities.

Chinatown was hijacked by Richmond. The Chinatown we are used to, including its restaurants and retails, will never come back; it is a nostalgic idea. We want the flavour and patina of Chinatown to never be lost. But we also need to address the contemporary needs. What does the community need? I employ 72 staff in Chinatown that eat in restaurants. Businesses cannot survive without people who walk to and from work in a neighbourhood. Everything needs a holistic approach. We need to ask ourselves: Where do we want to be in 10 years? The world is changing! We live in the 21st century and having Chinatown with the romantic idea of rickshaws, horses and buggies just doesn’t work anymore. Instead of appealing to these clichés we need to address diversity of people and diversity in housing stock and stores. I don’t want to see the businesses go to franchises.

JK: Neighbourhoods do change, there is always something closing or opening; it’s an evolution of a community over time. Simple change is not gentrification! Gentrification is a rapid process that forces change on a place, development displaces existing uses, attracting other new businesses, which drive rents up and soon the traditional neighbourhood disappears through no real fault of its own. You may only have the street signs left to recall an area. Chinatown is experiencing a demographic shift in the neighbourhood, which has seen many of the original storeowners in Chinatown retire. And with family members not wanting to take over the stores, the owners end up having to abandon their business. Chinatown is no longer the necessary centre for Chinese goods and services, which means the demand for many of the shops has diminished, too. And as this shift takes place, new businesses have appeared prompting an ongoing discussion about: what is an appropriate business for Chinatown?

But then you have this other conundrum, as you have the fight for Chinatown to continue to be a living, working neighbourhood; you have the tourists who are looking for the “Oriental fantasy.” Even in Vancouver’s tourism advertising about Chinatown, they talk about taking “the short trip to the Orient” in order to attract more visitors. Additionally, the new condominiums on Main Street and Keefer Street pose a threat to the neighbourhood, as these developments will bring in a mix of new people who generally have no connection to the neighbourhood.

We have vegetable shops for example and other stores that rely on people who buy products in order to cook at home. But if we have a demographic of people who want to primarily eat out, then these shops will be threatened. And on the flip side, the more Chinatown becomes a tourist destination, the more the shops are threatened, because they become photo ops but no one buys anything. So the threat comes from the new demographics, as well as the image of Chinatown being an “Oriental fantasy” that caters to the tourists.

MK: What happens with gentrification is that there are already expensive and highly gentrified neighbourhoods in the downtown. Eventually, there is no space for another high-premium restaurant, bar, shop etc. to be built. So there is a spillover effect. Many of these neighbourhoods are adjacent to or near the inner cities, where there is preservation of the historic buildings. These neighbourhoods become hotspots for speculation and gentrification. When the property values rise, obviously that displaces the local low- and middle-income population and small commercial enterprises.

This is also what is happening with Vancouver, where gentrification started in Gastown, and is now expanding to the adjacent Chinatown and further to the east. It starts with the bike lanes, art galleries and the Starbucks coffee shops. When there is a block of run-down, deteriorated century-old buildings and in between them you see a fancy bar or an art gallery that is a sign that this part of the city is going to, sooner or later, be gentrified…and you can say with certainty that low-income people will be evicted. This is what has already happened to the Chinatown in New York City and is in process in the Chinatown in Boston. The ultimate fate of most Chinatown’s in North American cities, unless these cities radically change their zoning and housing policies and the valiant work of civil society campaigns succeeds, is what has happened in Washington D.C.—that now has a Disneyland version of Chinatown: symbolically Chinese but with few of the Chinese residents who lived in this area for generations. This kind of approach will push away the businesses that have existed for decades and shaped the character of Chinatown.

One trick that cities like to use is that they deliberately let a neighbourhood deteriorate. And their reasoning is that they are doing this because the economy of Chinatown is very depressed and no one is coming to the shop in the stores. So, they redevelop all these parts to let businesses flourish and bring in people and businesses. But what they are really doing is gentrifying these parts. Aside from affecting the quantity of social housing, the quality of these buildings also has an effect of integrating low-income people into middle-class neighbourhoods.

Spacing: The 105 Keefer is to-date the most controversial real estate project in Chinatown. People are worried it will accelerate the gentrification of Chinatown and become a threat to the neighbourhood’s heritage. Do you think the community’s reluctance and active opposition towards this condominium project is justified?

BR: Politicians don’t want to take any risks of density! This is also reflected with the 105 Keefer project. The community missed an opportunity with this [105 Keefer] one. The fighting was all black and white. That is not how we humans survive. We should all work together and find a solution.

The trouble with Chinatown is the discussion about what heritage means and the conversation gets confused and is completely different than a conversation about a vacant site. The proposed 105 Keefer was going to be built on an empty parking lot. Yet, we allow heritage to be talked about in the same sentence as that of the vacant site.

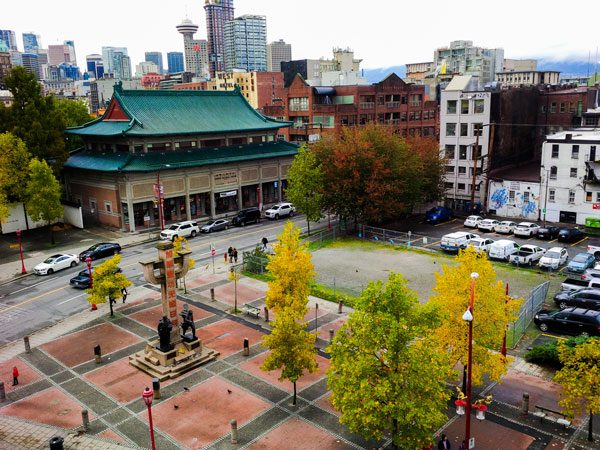

There is a memorial [Memorial Square] in front of the empty parking lot that nobody has paid any attention to for the last 25 years! But now advocates against the redevelopment of the 105 Keefer are paying attention to the memorial all of a sudden and are falsely fighting against the condo project. This means, we are at a crossroads now: the buildings on [the heritage protected] Pender and Keefer Street can either become “cheque cashing” stores or Seven Elevens, or the community can work to curate a vibrant retail street. The City should have a leadership panel to discuss where Chinatown is going. The direction will come through consultation.

JA: The community rejected the 105 Keefer proposal, as the developers did not take the time to engage with the community regarding the development. Not once did they show up to the adjacent Chinese Cultural Centre board, the Dr. Sun Yat-Sen Classical Chinese Garden board or the Vancouver Chinatown Revitalization Committee, or other organizations to feel out the community and develop an approach to the project that would enhance Chinatown and take into account the significant cultural heritage of the site. Given the bulk and size of 105 Keefer, the benefits to the community were pretty much zero.

The lack of respect shown to the neighbourhood was incredible. Had the developers included the community in their decisions it would have been totally different. Had they acknowledged the significant history of the site and its context on the edge of the National Historic District, next to the Dr. Sun Yat-Sen Classical Chinese Garden and fronting on Memorial Square [along Pender Street and Keefer Street] and used that to inform the architecture, the results might have turned out differently. But they ignored the community utterly!

Instead of engaging those with deep knowledge of Chinatown, they hired a heritage consultant whose heritage analysis missed the significance of the Chinese Theatre, which once occupied a portion of the site. The theatre opened in 1916 and operated until the 1960s. It was the largest Chinese-run theatre in North America outside of San Francisco, and as such it had a huge cultural impact on Vancouver. The theatre brought major opera stars from Hong Kong and Mainland China to perform.

The former gas station on the Keefer Street side of the site was bought by the Lee brothers after WW2. Hubie Lee served Canada in the war with distinction and was part of an elite intelligence squadron….again missed by the consultant.

MK: In the case of Chinatown, it is not just heritage preservation that is an issue. What we are observing is that there is a deliberate attempt to change the urban fabric through rezoning. The 105 Keefer Street development in Vancouver’s Chinatown is a case in point: an empty parking lot that is adjacent to the heritage-protected area (HA1 zone), with a vibrant community reflected in the [weekly] Night Market. The proposed development project [105 Keefer Street] is a private market condominium surrounded by heritage buildings. The City is claiming that they [the developers] are being inclusive by having affordable housing for seniors in that proposed building. But those encompass only 25 units out of 110. That is not a solution, as you are only giving a token of subsidized housing. It should be the other way around!

Spacing: Ever since the announcement of the Woodward’s redevelopment in 2003, private market developments in the Downtown Eastside—especially Gastown and now Chinatown—have been subject of heated debates. The community’s resistance towards the 105 Keefer is very comparable on the debate around the Woodward’s site in Gastown. When it was announced that the site of the former department store is going to be redeveloped into private-market condominium projects, the community showed strong resistance. That resistance, along with the Woodward’s Squat, led to 125 subsidized units out of the total 536. Opinions on the Woodward’s Redevelopment are split, as some argue the project displaced the locals of the Downtown Eastside, while others praise it for being a winning way to include different demographics in one building complex. Is the Woodward’s Redevelopment a good example of inclusivity?

BR: The safest and most conductive bridge between the fortunate and the less fortunate is through arts & culture or education and facility, because youth and intellectuals understand diversity. The idea is to bring the community together through arts & culture as well as education and facilities; this is what the Woodward’s does. The Simon Fraser University Campus inside the Woodward’s Redevelopment brought youth to the street and starts to bring balance to the street, as well.

JA: I think Woodward’s works and on many levels. The atrium space with the basketball hoop draws all sorts in for games; there’s the cultural space for groups as diverse as Vancouver Moving Theatre, Kokoro Dance, Simon Frasier University’s theatre program, studio space, cultural office space, and many more uses that provide activity and community access. This collaboration creates something that is really successful in the neighbourhood. I think a mix of housing types works better. Segregating people from different socio-economic backgrounds doesn’t work. We saw that sort of thinking in the 1950s and it didn’t work. It happened in Toronto, Chicago and London, where there were these housing projects that provided no social connection in the surrounding neighbourhood. I still think a mix of housing is preferable.

Some people may think that Woodward’s gentrified Gastown, and it certainly has had an effect on the surrounding neighbourhood, but what people need to understand is that it was actually the city’s ten-year tax break that facilitated the development in Gastown. It was a way to get the buildings in Gastown seismically upgraded and find a use for the upper floors, create a conversion of warehouses into residential buildings.

MK: There is all that rhetoric that suggests Woodward’s is a mixed-use building. But really, what is a mixed-use? It is a couple of units that are called ‘affordable housing’ in a primarily private-market building. The entrances for affordable housing units are separated from those of the private market units. That is segregation within a building! And the definition of affordable housing is very vague. What do they mean with ‘affordable housing’? Is it subsidized housing? Is it rent-geared-to income? Can the hardest to house live there?

The Woodward’s should have been all affordable housing, instead of only 125 units out of the 536. Why has social housing worked in many cities in Europe and other parts of the world? It has worked because all those low-income projects are well maintained and often placed in middle- and upper-class neighbourhoods. Hence, people who look at the buildings from the outside cannot make any distinction between poor and middle-income tenants. For example, in Geneva and Vienna some of the buildings that are social housing are architecturally the same or even better than those buildings that are in the private market. So why can’t Vancouver follow these examples and construct or renovate buildings and ensure housing that is liveable and affordable for all?

***

Read Part 2 of Vancouver’s Chinatown: The Dichotomy of Past and Present here.

**

Ulduz Maschaykh is an art/urban historian with an interest in architecture, design and the impact of cities on people’s lives. Through her international studies in Bonn (Germany), Vancouver (Canada) and Auckland (New Zealand) she has gained a diverse and intercultural understanding of cultures and cities. She is the author of the book, “The Changing Image of Affordable Housing – Design, Gentrification and Community in Canada and Europe”.