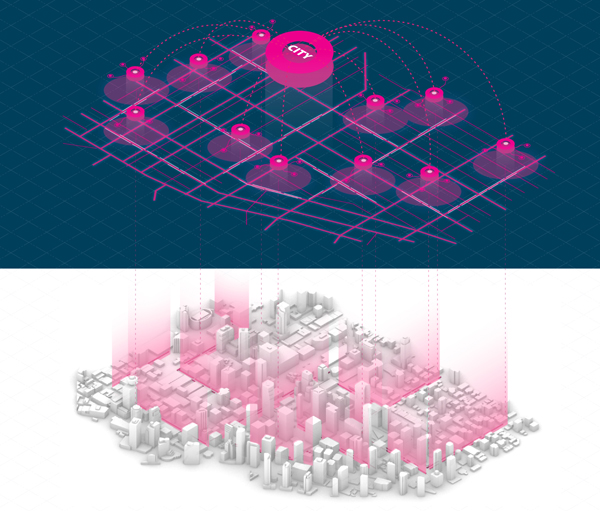

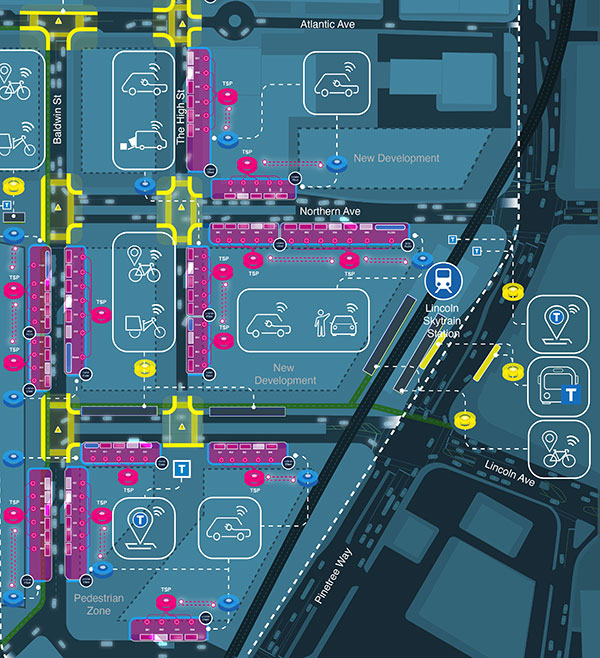

The virtual urban realm is a digital version of the physical city. It is represented graphically and geographically in real-time, through collected data that is analyzed, simulated, modified and controlled remotely. (Image by UBC TIPSLAB)

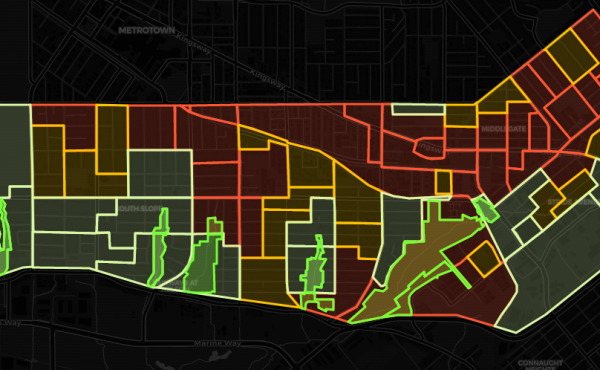

The virtual urban realm is a post-geographical territory to be explored. It can be—and is—represented through real-time mapping fed by data from connected devices and urban infrastructure. In this process, mechanisms are put in place to allow the physical realm to be managed optimally and controlled remotely. This may propel a gradual shift in power towards the virtual realm. While this shift could be harnessed to benefit the common good, it could also lead to excessive surveillance and suffer from coded bias.

Designing the virtual urban realm requires leveraging new technologies to address contemporary and future urban concerns. Within this context, there is a need for traditional built-environment professionals to take the initiative and engage in shaping the virtual urban realm.

The Post-Geographical World

In the past, maps were a revolutionary tool for navigation and exploration. At the same time, they were also a fundamental tool for colonization through land demarcation and appropriation. In the 21st century, the global power struggle is shifting beyond control over territory and geography: focusing instead on access to digital information and its resulting economic power. Or as Yuval Harari says “data will eclipse both land and machinery as the most important asset, and politics will be a struggle to control the flow of data“.

“That post-geographical feeling”—a contemporary sentiment expressed by Vancouver sci-fi writer William Gibson in No Maps for These Territories. In this film, shot in 1999 in the backseat of a car, Gibson talks about cyberspace colonizing real space. As cyberspace reaches into more aspects of our real-life it becomes naturalized. The colonizing power structure prompts the questioning of whether the virtual realm has increasingly more power over the physical realm.

In the not-so-distant past, it took a while for recent changes in the city to find their way onto a paper map or road atlas. Today, we can access up-to-date maps and recent satellite imagery virtually anywhere in the world. All of this information can be retrieved at any desired scale and in a matter of seconds. We take it for granted, but one of the most revolutionary features of the online map is that it is always current and repeatedly updated. In a sense, it represents geography that is in constant contact with activities in reality.

The marvel of real-time information that we end up seeing on a map also has its share of controversy. It involves the gathering of voluntary and involuntary crowdsourced data through surveillance algorithms—perfectly tuned to play according to the market logic of the data economy.

Digital Twins

In the future, data collection is projected to extend far beyond our personal devices and include vehicles, robots, objects, or sensors via the Internet of Things (IoT). Physical infrastructure and connected devices can be modeled and controlled remotely via a dashboard or an operating system, thanks to “digital twins”—digital counterparts of physical objects or processes. These real-time simulations operate in real-world environments providing a two-way communications channel between physical assets and their computer models.

Digital twins address different contexts and scales, from connected household products to building management systems, to city infrastructure. Simulations help engineers and planners make more informed decisions on the design and organization of the urban realm.

However, digital twins are not merely a virtual representation of their physical counterparts, but active agents in shaping the physical world. They can remotely control the behaviour of infrastructure and nudge the behaviour of humans through their devices. In the long run, the advancements of machine learning and AI could replace manual (human) decision-making with everyday operations. This raises inevitable questions around automation and the role that digital twins will play in this process.

Discussing how cities will look once full autonomy is achieved often comes with mixed feelings of both awe and incomprehension. Occasionally, techno-optimistic project proposals evoke tech-lashes (backlash against large tech corporations). However, there is no need to wait until “level 5“-style automation, as even partial automation, in the right circumstances, can have dramatic effects. In this context, designing the virtual urban realm could benefit from following an incremental and self-checking approach.

Designing the Virtual Urban Realm

The digital transformation of cities in the 21st century is much less visible, compared with legacy 20th-century urban transformations—think of highway construction erasing entire precincts, segregating and displacing communities. Only time will tell what the toll and scale of the impact of the digital transformation will be. In the meantime, we can delve into better understanding the virtual realm and develop futureproofing transitional strategies.

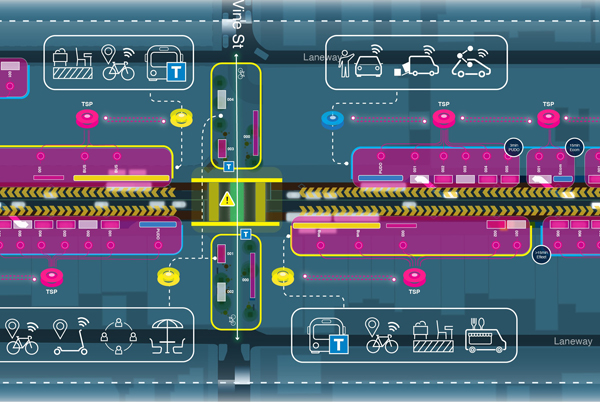

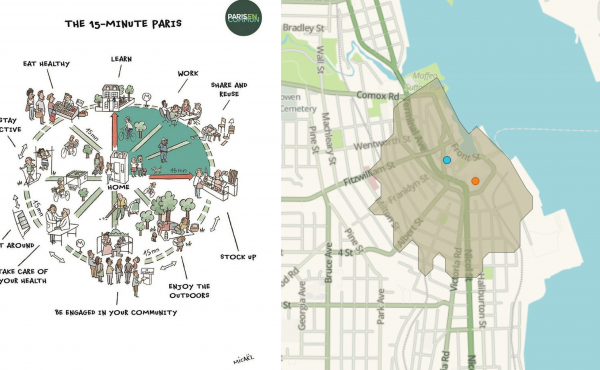

The challenge of designing the virtual urban realm requires leveraging new technologies to address contemporary concerns such as urban mobility. How can efforts to digitize the public space be used to prioritize sustainable modes of mobility? How can the (virtual and physical) urban interface address people-centric design and equity? How can access to connected and shared-mobility options be expanded to a wider population? A recent study looking at the transitioning strategy into new mobility addresses some of these questions. This study explores the potential design of (virtual and physical) curb space. This ubiquitous space is imagined as a fundamental building block of an urban Mobility Hub network, connecting the virtual urban realm.

Ultimately, design and planning professionals are shapers and programmers of ‘spaces’. They articulate connections between populations and locations, they revise codes and policies of usage of space. Seemingly naturally, designers and planners could take initiative and address the virtual/physical design challenge. There is an opportunity to shape the way the virtual urban realm changes our reality so that it aligns with values that benefit the greater good. In this context, designing the virtual urban realm may well be the next frontier of city-making endeavours.

***

Yuval Fogelson is an urban designer and explorer. Interested in the digital transformation of public space, he researched the transition into new mobility and future curb space design and is involved in curbside digitization working at IBI Group. He is an enthusiast for people-centric public space transformations and tactical urbanism. An imaginative city lover and map drawer. Contact via LinkedIn.