It’s not a good week to be a member of Vancouver City Council. Confronted with a final decision on the Broadway Plan, and now brutally aware of its potential impact on the five neighbourhoods that it passes through, previous decisions by both the province and the previous Vision council may tie their hands.

Eight previously approved neighbourhood plans will be rescinded if council passes the Broadway Plan, including the 2013 Mount Pleasant Community Plan Implementation. That’s right. Eight approved plans developed with rich neighbourhood consultation of the sort that made Vancouver famous for neighbourhood-based planning will be erased with the stroke of a pen.

As radical as this is, council may feel little choice in the matter. What ties their hands?

Contracts. Contracts with the city that, in effect, throw out all those plans in return for the $2.8-billion subway presently under construction. In June 2018 the city signed off on a Supportive Policies Agreement with TransLink, obligating the city to add unspecified new density along the corridor while agreeing to finish the plan by the end of 2021 (a deadline now missed). This agreement obligated the city to specify “the number of dwelling units and employment for the years 2025, 2030, 2035, 2040 and 2045” in this plan, timed to align with the construction of the new subway.

Penalties for non-compliance are not specified in the agreement. But the province is expressing dismay at the slow progress of the Broadway Plan and a corresponding enthusiasm for unprecedented new density on the corridor. So the possibility of the province assuming planning authority for the corridor, if the results of Vancouver council deliberations are not to their liking, cannot be dismissed.

Well, so what, you might say if you have arrived at the conclusion that Vancouver has long been stymied by the power of single-family lot owners who marshal NIMBY resistance to the kinds of denser zoning and affordable housing policies the city truly needs. If it takes the province to break that logjam, you might say, so be it.

I agree! In fact I’ve argued for years in these pages and elsewhere that Vancouver faces an affordable housing crisis and tinkering won’t solve it. Truly affordable housing, achieved in part through allowing denser building forms in return for truly affordable housing units, should be goal number one for our politicians. What I’ll try to explain in the remainder of this piece is that the Broadway Plan’s radical overturning of previous neighourhood plans can’t be justified with a guarantee that, in return, Vancouver will enjoy significantly more affordable housing or deliver the city from its dubious status as least affordable in North America.

And I’ll propose an alternative, and radical, version of the Broadway Plan that in my view would make new housing along the corridor far more affordable.

Is more housing supply alone the answer?

At the heart of this debate is a difference of opinion on how to tackle the housing crisis. Housing Minister David Eby recently voiced strong support for those who argue that the reason housing costs too much is that we lack “supply.”

While that makes intuitive sense, there is much real-world evidence that the affordability issue is not that black and white. For example, this council, during its first three years, has approved nearly 200 zone changes throughout the city, denying just one — which eventually was approved after design changes. Blogger Brian Palmquist worked off city records to calculate a figure that the city itself hasn’t shared. He concludes all the zoning changes amount to approval for over 20,000 units, and approvals are soon to be taken up for 20,000 more.

For a sense of scale, 40,000 units in less than four years exceed the 30,000 units proposed for the Broadway area for the next 30. If Eby is frustrated by the city’s unwillingness to add new supply, how does he square those figures?

In fact, no other centre city in North America has approved and built more new housing units per capita than Vancouver. Vancouver has increased housing units by 66 per cent since the 1980s, moving our residential density from 3,300 units per square kilometre to 5,500 in those four decades. This makes Vancouver the highest density city in Canada.

If high housing prices could be solved by adding supply, Vancouver should rank among North America’s most affordable cities. Instead, it is the most expensive.

Minister Eby and others might rightly ask: “If impeded supply is not the problem, what is?”

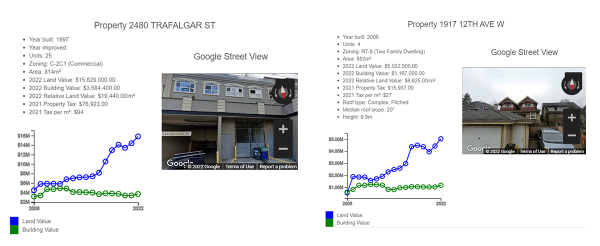

The evidence suggests that inflated urban land prices are the problem and that our efforts to make housing more affordable may be making it worse. Since 2006 Vancouver has seen land prices rise by over 500 per cent. And it doesn’t matter how big the building on that land is. The bigger the building the higher the land price, as illustrated below.

The value of land under Vancouver buildings is always many times more valuable than the building above it. So greenlighting and constructing bigger buildings does not always lead to lower rents or purchase prices. It does, however, put more wealth in the pockets of land speculators.

The result is that we are in an arms race against land price inflation that we haven’t positioned ourselves to win. We authorize new density in the hopes of diluting the influence of land price on project viability, but in the process signal to the land markets that their land just got a lot more valuable. Up goes the price, again and again.

What to do Minister Eby and Vancouver councillors? What to do?

Answer: Don’t just zone hoping it will result in affordability. Insist on it!

In fact, if city council or the province are prepared to tear up neighbourhood plans and impose radical new rules for zoning and density in Vancouver, what I will propose below might just be worth it. Because it would put a big dent in land speculation. And that would transmit to actual lower housing costs.

So here goes.

How to suppress land price speculation

Land price inflation can be controlled by insisting that at least 50 per cent of new housing be affordable to those making average wages and below. This requirement puts a brake on the “residual” value of development land while protecting nearby undeveloped parcels from the negative effects of property tax increases pegged to inflated “highest and best use” assessments. Who would build units under such imposed conditions? Not luxury tower developers. But non-profit and co-op providers are well suited to this task.

Vancouver of course takes a far lighter touch with developers. At best, zoning for more density in some parts of the city comes with the requirement that developments include 20 per cent of units be at “below market rates” which is usually still not affordable to those making average wages and below. Beyond that, the city works hard to encourage developers to build market rental projects by offering tax abatements.

Those tax break carrots offered by the city are granted in the hope that the resulting increased supply will bring down overall unit costs and rents. What it does instead, unfortunately, is produce a lot of quite unaffordable new units. New two-bedroom rental units on the Broadway corridor are already renting for over $3,500 per month. Expecting more buildings of a similar type to be cheaper than that is a chimera. Land speculators won’t let that happen.

Let’s put that $3,500 per month in context. In Vancouver today, the median renter household makes just under $60,000 a year. In order to afford that $3,500 rent at 30 per cent of income a renting household needs to earn at least $150,000 per year, putting that family in the top 15 per cent of household income earners in the city. This is why we have a crisis in Vancouver.

Has any city in North America done what I propose by insisting that no land will be zoned for more density unless the housing built is 50 per cent truly affordable?

One is Cambridge, Massachusetts, home to Harvard University and also a vibrant multi-ethnic population, many lower income. Cambridge had given new density in return for affordability at much higher levels than our current 20 percent at “below market rates.” One simple way to do this is in Vancouver would be by insisting condominium developments leverage one affordable unit for every unaffordable unit using the already legislated $340 per square foot development contribution expectations tax. This will produce billions of dollars — not out of taxpayer pockets but out of money diverted from the pockets of land speculators.

Put more of the new units closer to transit stops

A final suggestion. For decades I and others have argued for transit-oriented development. Notwithstanding the above, the science is clear: the most important catchment areas for transit are within 400 metres of stations. People living or working more than 400 metres away from stations have an increasing tendency to use their car instead of transit. This means that the efficacy of transit is much more dependent on new density near stations than further afield.

***

This article was published originally on The Tyee (05/30/2022)

**

Patrick Condon is the James Taylor chair in Landscape and Livable Environments at the University of British Columbia’s School of Architecture and Landscape Architecture and the founding chair of the UBC urban design program.