Amidst widespread housing instability, many feel that we may never again be able to dream of a home to call our own.

There’s a deep, unsatiated sense of longing for a space to hang up one’s hat, kick back, own houseplants, and make art to adorn the walls. A place to be yourself and never have it taken away from you.

Daring to Dream of Home in Bleak Times

Local artist Keely O’Brien’s ‘Dream Home Hotline’ project was inspired by a conversation with a friend, who has struggled to find affordable housing and art studio space in Vancouver.

“She told me that she didn’t even want to dream about her dream home anymore, as it seems so impossible to attain, so that thinking about it made her feel hopeless,” O’Brien shared.

The project invited the public to call in and leave a voicemail to manifest their dream home. They were asked to describe it in detail, the sky was the limit.

The ‘Dream Home Hotline’ project is in tune with those that dare to dream, reshaping their vision of what a home looks like. This type of creative reimagining has fueled a social and architectural rebellion, similar to the tiny house movement and off-grid lifestyles where people simplify and downsize their lifestyles to live with less and decrease their ecological footprint.

The Blue Cabin: Past and Present

O’Brien recently wrapped up an artist residency in the Blue Cabin, a mobile art studio currently situated on a floating platform in Steveston Village.

While most passersby might easily dismiss the cabin as another floating home—a common sight in the waterways of False Creek or Mosquito Creek Marina—the Blue Cabin is an almost century-old structure with many stories to tell.

The cabin is the last existing structure of its kind from an important time in Vancouver’s history, representing a lifestyle that has all but disappeared due to gentrification.

Built in 1927 by a Norwegian carpenter and shipbuilder, it was towed to the Cates Park area in 1937 and was hoisted up onto posts above the foreshore in a tiny cove. There it stayed for the next 83 years in a community of cabins that dotted the foreshore that was mostly without electricity, running water, or plumbing.

One community, in particular, called Lazy Bay, was home to more than 90 structures during that period. Among them, lived English novelist and poet Malcolm Lowry, and it was where he wrote his most famed novel ‘Under the Volcano.’

As the cabins were built right in the tidal zones, it was considered a legal gray area, which neither the city nor the federal government had jurisdiction over.

Anthony Meza-Wilson, the Blue Cabin’s managing director, explained how legal gray areas work in the context of the squatter dwellings. “Municipalities usually have asserted jurisdiction over the shore, while the federal government over the waterways. Cities reach to the high tide mark, and the federal government around the waterways only have it to the low tide mark. So the foreshore is an in-between zone,” he explained.

“All jurisdiction is incomplete in a way, and authorities hadn’t really considered what was going to happen in this area. They figured that people weren’t going to live on it because it was the tidal zone. But then, people started living on it.”

Among these people, laborers, seniors, artists, and counter-cultural creatives, was a spirit of a rebellion for those seeking to connect with nature and slip the bonds of social convention.

The idea of living a life unfettered by societal constraints can be easily glamorized, and Meza-Wilson reminds us that those living in the squatter shacks were likely doing so out of necessity.

“People can sometimes romanticize the lifestyle of those who lived in the squatter shacks on the mudflats, but in reality, it’s important to remember that it was a mixed community where there could be a lot of precarity, poverty, and hard times,” he said.

Al Neil and Carole Itter

In 1966, the artist Al Neil joined the community after receiving a tip that the Blue Cabin was available. He rented it from shipbuilders McKenzie Barge & Derrick for $15 a month, and the company provided electricity for the cabin. After some time as a tenant, Neil became the “unofficial beach watchman” for McKenzie Barge, and began living in the cabin rent-free.

A free jazz pianist, collage artist, poet, and assemblage artist, Neil was an “electric and interesting character from Vancouver’s art scene beginning in the 1960’s and 70’s,” according to Meza-Wilson. He was later joined in the Blue Cabin by his partner Carole Itter—a performance artist and assemblage sculptor, who made musical, large-scale wind and water chimes.

“The two of them lived and worked in the cabin up until 2015,” shared Meza-Wilson. “They’re the ones that created this patina paint interior and this is how it was when they were living in it. They were just a pair of bohemian artists living on the beach, making assemblages in and around the cabin and doing other creative work.”

After decades of living on the Dollarton Foreshores, their time on the beach had come to an end. The land next to the cabin was bought by Polygon Homes in November 2014. Neil and Itter were served with an eviction notice, and the cabin was ordered to be removed in just two months’ time in January 2015.

Neil was almost 91 years old at the time, and the pair packed up their lives and relocated to Itter’s Strathcona home that she luckily maintained throughout her time at the Blue Cabin.

Sadly, some of the other homes in the area met an untimely fate, as the community was displaced to make way for where Cates Park is today. The Blue Cabin, though, was spared due to its connection to Mckenzie Barge and Neil’s role as an informal watchman.

Reflecting on the Blue Cabin’s Story

The past is a reflection of the present, and O’Brien has witnessed the old being bulldozed to make way for the new.

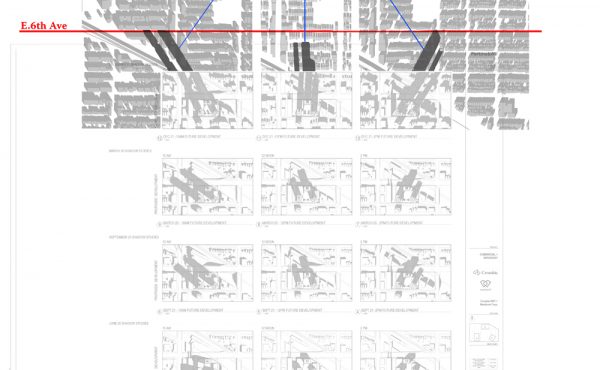

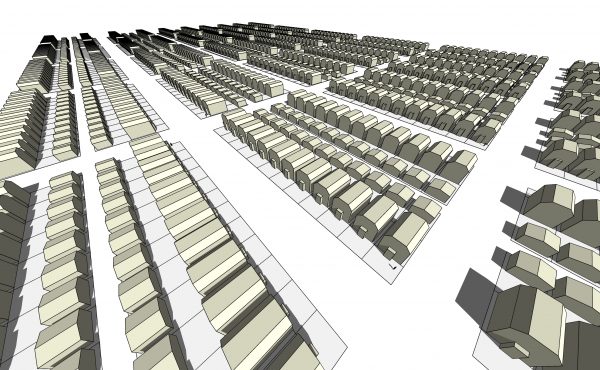

“The cabin’s visible connections to the past starkly contrast my own current home: I live in a condo where there isn’t very much indication of the deeper past at all remaining in the landscape. Everything is new, concrete, and even the last few old trees in my neighborhood are coming down to make way for development,” she lamented.

Many of us can relate, at varying levels, to the traumatic feelings that swirl around neighborhood loss. All the while, cities have the arduous task of balancing the negative impact of social change to communities with accommodating the growing population.

These social issues increase the importance of projects like the Blue Cabin artist residency, living on as a nomadic beacon of resilience for those who long for a home to call their own.

O’Brien feels that the cabin represents a dream home for many of those who are faced with shrinking opportunities for affordable, creative living. “The cabin has felt like a dream home to me, a place I could only dream about inhabiting, with qualities of history, personal expression, and closeness to natural landscapes that are not in reach in my current home,” she said.

Her time with the cabin seemed to be a reminder that amidst tough times, we should still allow ourselves to dream. O’Brien wondered: “What would happen if we allowed ourselves to dream of a joyful and secure sense of home, even in bleak circumstances?”

**

Iris Leung is a freelance journalist based in Steveston Village, interested in writing about urbanism and gardening.