EDITORS NOTE: This essay on the Grand Trunk Railway first appeared in the Toronto Star’s Insight section on March 1. It is reprinted here with additional images. Photo above of the GTR Viaduct over the Humber River near Weston taken by Prof. Paul Gauvreau, Associate Professor of Civil Engineering at the University of Toronto.

Standing on Fort York’s south ramparts, eyes wide shut, it’s easy to imagine Lake Ontario is only a few metres below. The hum of the Gardiner Expressway even sounds like the surf. But open your eyes and the freeway looms on its concrete columns, and you must look between condominiums to catch a glimpse of the distant water.

On the north side of the fort are hints of why we have Toronto terra firma where the shoreline once was. Nearly a dozen rail lines cross Toronto near this spot; one branch heads along the lake towards Hamilton, the other curves northwest towards Weston and Georgetown. The latter follows some of the historic Grand Trunk Railway route, built during Toronto’s first era of railway development.

Soon, the 19th century route responsible for so much of the city’s early growth may play a key role in the evolution of 21st century Toronto, by serving as backbone of the long-sought rail connection between Union Station and Pearson International Airport.

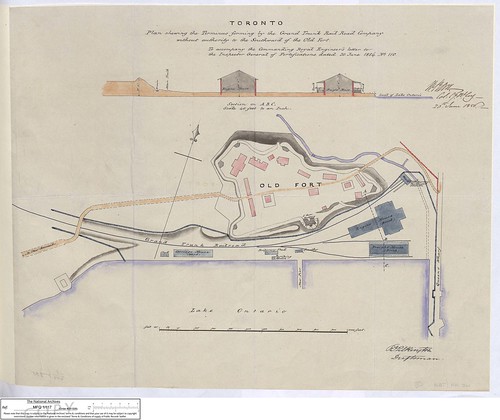

Map showing Fort York GTR Terminal from 1856. Larger size found here.

The name Grand Trunk still sounds expansive; it is a reminder that after the War of 1812 railways, not armies, started to decide Toronto’s future. The Grand Trunk would grow, as planned, into a main trunk line — becoming for a time the world’s largest railway system — and finally morph into CN. But when first built, the Grand Trunk did not even cross what is now downtown Toronto. It swung down toward the lake from the northwest and stopped at a terminal on the south side of Fort York.

Above four photos taken in November of the railcut & Strachan Ave. overpass.

Evidence remains, in impressive earthworks visible between the fort and Strachan Ave. In the shadow of the Gardiner near here is an old trench that was dug west to Strachan, where it curves north and now disappears, with few traces, under modern Liberty Village.

The Grand Trunk was originally chartered as the Toronto & Guelph Railroad Company, and became part of plans for a railway between Toronto and Montreal and southwestern Ontario. Between 1853 and 1856, lines were built in two sections: Toronto to Montreal and Toronto to Sarnia. Engineer Casimir Gzowski was the contractor of the western section, and his Grand Trunk accomplishment is one reason the lakeside park west of Sunnyside bears his name (he is also the great-grandfather of the late CBC broadcaster Peter Gzowski). The large terminal yard for the Sarnia line was constructed in front of Fort York on eight hectares, about half of which was landfill, thus beginning the shoreline’s slow move south to its current point across from the Toronto Island Airport.

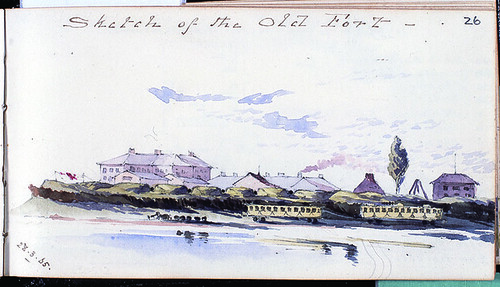

GTR terminal with trains on then just-extended waterfront can be seen above in “Sketch of the Old Fort” — Watercolour by Captain J. Elgee, 34th Regiment, 1865, National Army Museum, London.

More than anything else, the railways were responsible for the extension of Toronto’s waterfront, because they had the political and financial muscle to get what they wanted (the term “railroaded” means what it does for a reason). There was a gap between the Sarnia and Montreal sections of the GTR for only a short time before the railway bullied Toronto City Council into letting it lay tracks across the front of the city along the newly created Esplanade, marking the beginning of the city’s estranged relationship with its waterfront. In the late 1850s, the view from the Fort’s bastions was still of the lake, but also of a busy Victorian industrial scene.

Today’s Pearson rail connection proponents may wish they had the same bullying power their 19th century counterparts did. The various schemes proposed — such as the early Blue 22 line that involved diesel trains running regularly between Union and Pearson — have met with opposition in Weston. Now part of Toronto, Weston flourished once the Grand Trunk was established in the 1850s. One proposal for the Pearson link would have closed some surface streets, threatening to cut the community in half. The trains are welcome, says the Weston Community Coalition, but “Let’s build it right the first time” by burying the tracks and creating a Weston station, as there is with Go Transit — ideas that made it into later proposals.

Such discussions were unheard of when the Grand Trunk was built. The Fort York yard itself was formed by dumping fill behind a line of 62 massive timber “cribs,” filled with dirt from Garrison Common (a vast tract of land that included what is now Exhibition Place and the residential neighbourhoods to the north of the Fort) and from the GTR cut itself.

Archeological issues were not considered then, so the railway was able to carve its trench through the heart of the 1813 battlefield. That’s the equivalent of doing the same thing through the Plains of Abraham in Quebec or Gettysburg in Pennsylvania, and it’s probable that the fill still contains cannonballs, artifacts and even human remains. The site is so important, historically, that the City of Toronto is seeking to have Fort York recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, a process that will take years. As for the railway itself we tend to either take it for granted or else complain that the tracks cut the rest of the city off from the lake. David Monaghan, curator of the House of Commons and former curator of the land transportation collections at the National Museum of Science and Technology, says that “One of the great tragedies of Canadian Industrial and Transportation history is that so little remains of the original infrastructure that played a critical role in the development of the first railway networks in Canada.”

With this sentiment in mind, that lonely trench under the Gardiner suddenly echoes loud with meaning, as it was one of the reasons Toronto grew as a city. The Grand Trunk connected Toronto to Sarnia, where a ferry (enhanced in 1891 by a rail tunnel) crossed the St. Clair River to Port Huron, Mich., allowing cargo to connect by rail to Chicago, a big market for Toronto’s industrial might. Though there is a huge rail enthusiast community (just Google anything railroad and see for yourself), the on-site heritage here has not yet been interpreted for the public (though is elsewhere at the Toronto Railway Historical Association).

Looking west along GTR railcut & Strachan Ave. overpass in 1959, just before Gardiner was constructed. Photo by R.L. Kennedy at Old Time Trains.

As late as the 1950s, just before the Gardiner was constructed, photos of the rail cut show a bucolic scene resembling rural Ontario more than the centre of a great metropolis. Rail lines in general tend to have a country feel, often with antique wooden electrical poles and wild tall grasses and feral bushes. They are linear countrysides surrounded by urban landscape.

This short part of the Grand Trunk cut can only be followed to about Strachan Ave., and it won’t be part of the new airport link. But there are ghosts of the GTR on the GO Train’s journey west to Georgetown that will be, and that yet today demonstrate why the Grand Trunk was indeed grand.

GTR Viaduct at Georgetown over the Credit River by Paul Gauvreau.

Toronto lies in a region of ravines, and the Grand Trunk’s builders had to build substantial bridges across wide valleys. Golfers at the Weston Golf and Country Club in the Humber valley, just south of the 401, today tee off to greens below the Humber Viaduct, 170 metres long and standing on eight piers 20 metres high, soaring today just as it did in 1856 (see photo at top of this post or go here for a circa-1860 view). Further west, just outside of downtown Georgetown, is the similar, 300-metre-long Credit River viaduct with piers made of stone quarried nearby.

In his 1855 inspection report, Fred Cumberland Esq., chief engineer of the Ontario, Simcoe and Huron Railway, wrote that they give “such complete assurance to the mind of permanent stability.” His words ring true today, as these structures continue to serve as reminders of the industrial foundations that this city and country were built on, and are still rising from.

24 comments

Interesting and informative, as always! Thanks, Shawn.

*Oops, i thought going by the first photo, this was a post on the new themed park goin up on Front St(*between Strachan and Spadina)

Great post nontheless. Very informative.

Good article – it is well to remind ourselves that our city reflects investments and efforts made a much as 150 years ago and these things are still here today. Having said that, it is discouraging that our government just can’t seem to get it together. Such things as a few miles of track – which would have been trivial for our forefathers – are now like pulling teeth to get done. A few more “bullies” wouldn’t entirely be a bad thing.

It’s interesting to look at the area in Google maps:

http://maps.google.ca/maps?f=q&source=s_q&hl=en&geocode=&q=toronto,+on&sll=49.891235,-97.15369&sspn=43.813749,111.621094&ie=UTF8&ll=43.637682,-79.412946&spn=0.005971,0.013626&t=h&z=17

You can see the line of trees passing under Strachan, a rough path curving to join the existing railway lines, and if you follow the line to the right, you can see the line of East Liberty, the northeast face of the Toy Factory lofts, and through where the Libery Village LCBO now sits, where the bridge over King street is bent to meet it.

Fascinating stuff. Further west, look at the shape of the streets around Queen and Niagara, and follow the curves…

Take two on that URL:

http://maps.google.ca/?ie=UTF8&ll=43.637861,-79.411089&spn=0.004612,0.010536&t=h&z=17

Excellent article.

The Grand Trunk line described in the article opened on October 18, 1855 when the railway began regular passenger service between Queen’s Wharf in Toronto and Brampton, Ontario.

The Montreal-Toronto and Toronto-Stratford sections were joined in February 1857 when the GTR opened a new passenger station at Front and Bay streets. The line wasn’t completed to Sarnia until 1859.

Unfortunately Toronto has already demonstrated its callous disregard for our Grand Trunk heritage when the western pier of the railway’s 1856 bridge across the Don River was dismantled as part of the West Donlands redevelopment a couple of years ago.

Derek Boles

Historian

Toronto Railway Heritage Centre

Interesting that what destruction the “Grand Trunk” did railroading its tracks through Toronto in the 1850’s, but now we get upset if someone dismantles what they did.

The photo of mine shows the CPR wharf lead to Parkdale Yard, not GTR.

Just to clarify: The line pictured was the CPR Wharf Lead from Parkdale at the time it was photographed. Before the CPR acquired the line in its takeover of the O&Q which already controlled the TG&B it had been leased by the TG&B from the GTR. Originally, the OS&H (Ontario’s first railway), later, Northern Ry. of Canada owned shops where the line deadended along the south of Fort York at Bathurst Street.

It had nothing to do with the GTR line through Weston.

Thanks for the clarification — the rail cut, though, was the GTR cut originally. That is what I understood via other research — by ’59, it was used by other lines….is this correct?

@W.K. Lis: it’s about context. We should certainly try to understand and learn from what the Grand Trunk Railway did in the 1850sâ€â€just as we should learn the lessons of the Gardiner Expressway a century later. We should protect tangible aspects of that heritage where we can, as an aid to our collective memory if for no other reason. That doesn’t mean we should follow the example of the Grand Trunk Railway (or the Gardiner) when building new infrastructure.

It would be great if the Waterfront West LRT could use the railcut near Strachan Ave. I haven’t seen the latest options presented for the WWLRT but this route could speed the LRT past the busy Queen’s Quay track as an express option between Bremner Blvd & Union Stn, and west towards Queensway and Etobicoke.

Lovely article, Shawn.

Yes, we need to know our history, but we need more of the context around how the railroads got the land as it may have been beyond mere “railroading”. Perhaps to the point that maybe we should ensure that the public interest is directly served here.

There’s also the current opportunities – and the DRL is the higher best use of the corridor, apart from some GO expansion.

Shawn:

Originally this was the Ontario Huron & Simcoe, Ontario’s first railway. It became the Northern Railway of Canada. It ran through Parkdale, Davenport etc. to Bradford and eventually Collingwood. Grand Trunk took over the Northern. Toronto, Grey & Bruce leased the line from the GTR c.1871. Ontario & Quebec acquired the TG&B and the CPR acquired both. It therefore became CPR in 1883 and remained so until abandoned.

As far as I know the GTR line to Stratford ran from near Front & Brock (Spadina) via Strachan Avenue level crossing just south of King Street West, Parkdale, West Toronto, Weston, etc, to Stratford and London. I don’t believe trains on this line used the track south of Fort York which became known as the CPR’s Wharf Lead.

The only problem is for the GTR line to get to the Fort York terminal the line had to swing down below the fort, from the west. If you look at the map above (click on the link to see the larger image) you can see the GTR line is marked, exactly where the old railcut runs below the Gardiner and under Strachan today (and that your picture shows in 1959).

The line that ran south of the GTR main line to the south side of the Fort was originally the OS&H (Northern) GTR line. It and the facilities (engine house shed etc.) were at a dead end.

There was a roundhouse and yard on the north side of the Fort which was the GWR (later, GTR). Later, bigger facilities were built by GTR at Brock and Front. Either of these were far more likely to have been where trains to/from the Stratford line were handled rather than the tiny place on the south side of the Fort which is why GTR leased it to the TG&B (which they controlled for awhile).

Mike,

That is the precise option we are seeking to preclude, not only for reasons of avoiding a compromise to the nomination of FYNHS to the World Heritage List as directed by Council last Spring, but if you have visited the fort in the last few years you will realize that public transit has, or has the potential, to close off the site from any vehicle access to the surrounding city. This is unaccceptable for school visits, tourism drop-off, handicapped acccess, etc. Moreover, the FY Armoury is part of the FY National Historic Site due to revert to city-ownership by 2031 or earlier when DND vacates as it must under a century-old land lease. At that time a use for the armoury must exist that is not entirely circumscribed by arterial roads and dedicated transit rights-or-way. You may find it odd to know that the armoury site is the only site in the whole FY neighbourhood identified for public and separate school-use.

Stephen Otto

Mr. Kennedy,

For a very brief year or so in 1856-57 the Grand Trunk Western had its yard south of FY, while the OS&H slipped by across the north side of the fort to its growing complex south of Front, east of the road to the Queen’s Wharf and west of Brock. The Shanley Papers at OA document the filling of the FY yard and construction of the GTR’s brick, cruciform engine house at the east end of the yard. After the GTR western and Toronto-Montreal parts were joined along the front of the city, and the GTR began trading lines and taking ownership in the Northern, things got muddy or, shall we say, hard to follow. But that is the south edge of the Strachan Avenue Military Cemetery we see in your lovely picture of 1959, which can be located on that 1856 plan from the PRO London. And thank you for being there that day in 1959 to record for us one last, sad glimpse of a very short section of Toronto’s earliest railway history.

Stephen Otto

Great article!

I was down at the Fort last month and thought to myself that it looked like RR tracks went through the area. It was great to read about what used to be there and how the Grand Trunk shaped our city.

Stephen Otto:

Where can I view the 1856 plan from PRO London?

Can you e-mail me a copy? TIA

I have based my writing on the book The Toronto, Grey and Bruce by Thomas Mcllwraith,Jr. (p.8) However, I do not know the source of his research.

I have been conferring with Derek Boles in connection with this history and his only source is a Globe newspaper ad of October 18,1855 announcing passenger service between Brampton and Queen’s Wharf. This does not locate the wharf lead. There was more than one such track going down to Queen’s Wharf.

BTW The Grand Trunk Western was an American railroad and did not enter Canada. The GTR took over the Great Western which included a branch between Hamilton and Toronto. The GTR built its own line between Toronto-Weston-Stratford-London.

One thing is for sure, the abandoned right-of-way beneath the Gardiner Expressway is NOT the original Wharf Lead. It was relocated to permit construction of the elevated road.

Raymond Kennedy

I overlooked the map in the above article which I see is dated 1856 and shows GTR as the railway south of the Fort to the Queen’s Wharf. The 1884 Goad’s Atlas on my web site shows it as being the TG&B.

GTR operated the TG&B from mid-1880 until O&Q leased it Aug.1/1883.

Mr. Kennedy,

Currently I am in hospital being treated for a serious illness and would like to leave our discussion until better times. I know Tom McIlwraith’s work and respect it, but at FY we are dealing with a period of brief arrangements by Casimir Gzowski and David Lewis Macpherson to construct and profit from the line to St. Mary’s. I walked much of it last summer with Prof. Paul Gauvreau. In the Shanley Papers and at Ontario Archives, and in Richard White’s splendid book on the Shanley brothers, there is ample evidence that the Toronto & Geulph (olim Grand Trunk Western section to some until it connected with the Toronto-Montreal main line, had its construction base in front of FY on a 20-acre yard that ultimately was overshot on the north side of the fort by the OS&H and GWR as they swept north of the fort. The GWR’s buildings were more directly north of the fort while the grounds of the OS&H stretched from the road to the Queen’s Wharf to Brock [Spadina]. City of Toronto Archives has a wondeerful suite of photographs of the OS&H (by then Northern) yards and buildings ca. 1865.

Stephen Otto

beats me why the rail line for all these years hasn’t had a station to serve Pearson airport, from both directions. the line comes SO close.

contrast Gatwick airport here in England, where the rail station is right UNDER the airport. you need only an elevator ride to reach the trains from the planes.

makes me mad every time i come to Canada, having to endure the bumper-to-bumper 401 traffic all the way to Kitchener, while the existing rail line is so underused.