The Star reports today that a deal has been reached on the development disputes in the Queen West triangle (some other concerns, such as height and architectural context, still exist). But while that dispute might be settled, it’s just one scuffle in a much longer and citywide conflict that pits community (particularly low-rent and artist communities) vs. developers.

What is to be done about these kinds of problems? They sure aren’t going away. Well, it’s surprising in these circumstances how cogent the advice of a monied, jet-setting starchitect can be. Talking (and admittedly perhaps goading) Will Alsop in an interview last month, he surprised me by noting that part of the problem is that Toronto doesn’t have an affordable housing requirement for all developments. And that it darn well needs one.

As you likely know from the monthlong media buzz, Alsop, who is himself designing one of those disputed condos in the Queen West Triangle, currently has an art show on at the Olga Korper Gallery. The show, which runs to July 28 features—interestingly, given uproar over his development record—somewhat elegaic drawings of everyday-life detritus (shoes, lamps, pens, etc.) superimposed onto clean white cubes (symbolically, Alsop’s brand of neomod building).

As a visual arts critic, what came across for me in the drawings (both prior to and after reading Jon Lorinc’s Globe article about Alsop’s potential plans for Kensington Market) was a tension between a love for certain aspects of the low-rent boho life (Alsop’s known for his love of bar patios, and doesn’t mind a good cheese every once in a while) and a building practice often thought to extinguish such forms of neighbourhood dynamic. And as a low-rent kind of gal myself, what also came across was that Alsop was aligning himself, both through the show and in conversation, with a “love of art and artists,†but was actually being accused of ruining artist life in the Queen West area.

I’m running my gallery interview with Alsop almost in its entirety below so you can decide for yourself what Alsop’s intentions are. It’s long; the more flowery stuff is at the beginning two-thirds, the more thorny stuff (including affordable housing questions) at the end, if you’re short for time. Let me know what you think.

Interview: Will Alsop, June 7, 2007, Olga Korper Gallery

Q. So, let me get this straight, you have five offices around the world, you’re hopping from city to city, you’re super busy; so what is it with this painting thing, where do you find the time?

A. Well, I always have painted. I’ve always been associated with the way that art, either through friends or by going to art school, I did go to art school. And studied art, whatever that means.

I suppose my real closest friends are artists rather than architects. So it’s always around me. I spend time in Norfolk with my good friend Bruce MacLean, he’s a very good painter, and we just paint. We do other things as well. It’s just pure luxury.

And I have a house by the sea in England and a studio at the end of the garden. That’s where these paintings were made.

Q. Oh really? So they were based on Kensington Market, but made in England.

A. Yes, that’s right.

Q. Let’s say when you’re travelling then, how do you gather material for the paintings?

A. Well, in this particular case, I got the material just by hanging around, drinking, watching people and thinking about the place. And then I had a lot of photographs as well, which helped just to bring it back. And I just think it’s an interesting area.

Q. How so, what’s your favourite part about it?

A. Well, what really interested me was a number of things. It’s been messed around, but it’s been messed around by the people that live there. That is clearly very scruffy, and grotty in many respects. Yet because of that it has a vibrancy. In a way it represents the opposite of if you gave it to an urban designer and said do something with this, it would actually just sanitize the whole thing, and you just know that. So one thing that interests me is a lot of people go there so obviously there is something about that market that people like. Otherwise they wouldn’t go. And it’s not just needing a cheap T-shirt or whatever, it’s just a good place to hang out. There’s some good cheese, good meat and good vegetables, as far as I can see.

So I was interested in that, and I was also interested in walking around you can see the Central Business district. It’s very close. And then you wonder, hmmmm. How long will this stay like this? How long is it before someone starts to put their mucky fingers on this place? Then you come to the conclusion that’s going to be inevitable. And therefore I start to ask myself the question, how could you allow a place to evolve, which has already evolved anyway, it’s not the same way it was ten years ago or 20 years ago. It fought off the threat, as I understand it, of a main road in the 60s. And it’s probably that sort of point strengthened the sense of community there. But… how could you allow to evolve a bit more quickly? How could you increase the density? There’s not that many people living there.

Q. Yes, it’s lowrise buildings.

A. Because you have to equate that with the idea that more people should live near the centre of the city. In my view, it has nothing to do with community or anything else, you can’t take something that is quite a large area, right in the middle of the city, and leave it low-density out of nostalgia. That’s my starting point, yeah.

Q. But it feels like there’s a tension in the works. One thing that really struck me, maybe it was with a couple in particular, is that your work comes out of many traditions, one being the modernist tradition, like the tabletop you did for OCAD. And in some paintings you have things that look like that, like a rectangular cube, it’s pretty simple, and then it’s splashed with like, coffee or all this earthy looking stuff on top of it, lampshades and fountain pens, shoes maybe. And I was like there’s a real contrast here between what you’re drawing and the architecture that seems to be behind it, like your own architectural practice. Did you feel that at all? Was there a tension in between, I make these new buildings, but this area is messy and it kind of works?

A. In a way, simple answer is yes.

Q. Ok!

A. But I’m pleased you see it. I mean, all of those objects are things that I saw in the market. Some of them you use them and they’re very common garden objects, and some of them are extraordinary objects. There’s one jug that’s just beautiful. I’ve never seen a jug like that. Maybe it’s the only one in the world, who knows? But it reminded me of some of Picasso’s ceramics, which is probably why I was attracted to it, why I was drawn to it. Maybe it was one of his!

Q. Well, he would have probably lived in Kensington Market if he had lived in Toronto… before he made a lot of money.

A. Uh….. I don’t think so. But with all that side of it, I was interested in the relationship between those objects in the Market and some of the objects on a much larger scale that that you might introduce into the market which could be called buildings or workshops or studios or whatever. But the shoes, they had a certain symbolism. I had a title Going for Gucci — do you want Gucci in that market? Probably. I’m not against that. But it’s not all Gucci, so there’s that mix of cheap and expensive that is an interesting mix. Will it ever work? I don’t know the answer.

Q. So you work on this stuff all the time, and you’re still pondering this question.

A. Sure. Neighbourhoods like that are quite rare. There’s one I can think of in London. Portobello Road, of course, is another sort of street market. And the area around it is now unaffordable.

Q. It’s quite unaffordable, so it’s gentrified.

A. Sure. But the market itself, this is what interests me, is still very affordable, more or less. I mean, it’s obviously changed. In terms of the stalls, the way it looks, and this combination between actually quite expensive antiques and really cheap crap. I think that the film Notting Hill had a real effect on the price of houses around there though.

Q. Really? That it kind of went more upscale after that?

A. Yeah, a lot of Americans would come over and think, ah, that’s where I want to live.

Q. Yeah, Hollywood movies can really have an effect like that.

A. In any case, this is how some of the architecture work comes in to being,

by looking, thinking, relaxing, dreaming.

Q. I read in one of the pieces doing research for this that these were part of the sketching process for your work. Like finding the form of the building in the painting and then working inwards.

A. Yes, well, it’s not always the form, it might be the feel of a building. And I like painting because it’s very imprecise. In my studio in London I have a large wall with a huge piece of canvas on it. And it’s like, one page of your sketchbook. I might sketch out or paint out or whatever, and one canvas might hold ideas for two or three different projects which I’ve got in mind. And then I take it down and put up another one. It’s like a giant page.

One thing is though that painting is unbelievably tiring.

Q. Really?

A. Oh yeah, you have three to four hours solid working, you really really feel you need a bit of a rest.

Q. Hm. You find architecture easier, then?

A. Oh, yeah. I think it’s dead easy. [Laughs.] Politics is something different, of course.

With painting what I’m looking for is something that, and I hope this doesn’t sound pretentious, but something that’s behind the canvas. I want to see beyond what I know. And I haven’t reached any conclusion yet. Because they are done as works in themselves, so they’re just posing questions. In architecture you have to go on and get into answers. I don’t like the word solutions, because perhaps it was never a problem in the first place. But um, some recommendation as to how things might change and where they might lead.

And you know, as you get older, it is very easy to actually take an area like that and think, oh, it needs one of these things, and one of those, and one of those, but it never ends up like that. It’s testing things out. Wheareas the paintings are a less precise way of testing things out.

Q. And how many of these do you have? It must be a massive volume, if you’re doing it a lot.

A. For this series, I did about 30, and I sent 22 here, and I think they have about 15 out there. I don’t do it all the time. Sometimes I stop, sometimes I use the computer. You can work all day on a computer, less time on a painting. Not so good for the eyes, but you feel tired but in a different way. You end up with something. But it’s not as satisfying, actually. What I feel I’ve achieved, it’s all locked up in this box. You have to print it up. And even then, it’s not quite the same.

Q. You’re sketching all the time. You must have more ideas for buildings than you have projects. Do you think, oh this imaginary building would be really nice, and then keep ideas in your mind, store them away until they are useful?

A. I have a great many sketchbooks, and I might note an idea in there. But one thing is I never look at them again, when a sketchbook is finished it goes on the shelf and that’s the end of it.

Q. But you don’t throw them away.

A. No, no I don’t. I wish I could, but I won’t.

Q. And the paintings too, do you keep them all?

A. I have a number of storage facilities. A lot of artists of course there’s things they don’t sell. It’s good for their family, it’s good for their legacy, because they increase in value when they die. I mean the whole art market is something I feel it’s good I’m not a part of. Because I don’t have to be.

Q. You are right now.

A. Yes, I’m selling these, but I don’t have to. My wife doesn’t depend on that. So I can work outside the gallery system. It’s nice to be here. I like this gallery a lot, I like the space. It’s calm and Olga lets me smoke inside and it’s just great.

Q. Let’s switch to more Toronto questions relating to potential conflicts in your worldview. So let’s say you’re working on these condos in the Queen West Triangle. And there’s been a lot of contestation of that space. You’re not here all the time, but community groups and activists and artists groups are saying “no condos in my area, don’t kick me out of my building.†One of the condo projects will kick some artists out of their loft spaces. Considering that you’ve tried to integrate community feedback in some of your processes worldwide, what do you do with stuff like that?

A. Well, I think you have to talk. You have to talk rather than just work behind their backs. Um, and I think one thing is that change is inevitable. It really is. And to be honest, that area opposite the Drake is not very good. Kensington Market is grotty, but it’s interesting. And lots of people go, so that’s perfect. But not lots of people go down there [Queen West Triangle].

I don’t think anyone has a right to stop things from happening. You have a right though to contribute to the debate of what else could go there. And that’s what I try… I like working with people and knowing what they have to say. Sometimes they abuse the invitation when I try to draw them in. And some of them just worry about their taxes. I can’t do anything about that. But I can make a place which perhaps does reflect some of their dreams and wishes and desires. Sounds arrogant, but it’s not meant to be. And a place that might be completely different.

And what I do find is that what people do like is — and this is probably one of the reasons I like Kensington Market — they like their place to be different to everywhere else. They want some group quest for individuality and I think that it’s very easy for some communities and action groups to actually think their place is better than it really is.

Q. So you’re saying that it can be made better if you guys are willing to change it.

A. If it’s going to change, which it will change, then how do you go about that? What’s the nature of the evolution. Do you have to knock everything down? So with these artists just behind Woolfitts, it’s actually an appalling building, it’s in appalling condition. They live there and I assume it doesn’t cost them much. So okay, you need somewhere to live, somewhere to work, that’s not too expensive. What can you do about that?

Oh well, perhaps we could — and these are idiotic figures — we could build 150 floors, on that flat share of land and then get that invested back to pay for better studios for you, and maybe there’s some affordable units in the tower and then you live and you work in the same area, what’s the difference.

So height’s not the enemy. Density — there is a responsibility that the whole city of Toronto has — and indeed, many other cities — to increase density in the downtown areas. And West Queen West is downtown. Whether you like it or not. And you can’t just leave things. Because if that’s their attitude of “no change,†it actually results in mile after mile of subdivisions as you drive north of this city. And that’s highly irresponsible.

Q. What do you do about the rent situation though? The concern is that if you give developers free reign, that would push many poor people out to the suburbs.

A. Well, that’s a policy for the city to determine. An affordable units policy. A lot of places in the world do have one. Why not Toronto? If you, as an investor, are going to make money in there, 40% of what you do has to be affordable. Done! No argument.

Q. So you’ve dealt with that before.

A. Yeah, absolutely, all the time. In London, you have to do that. And if you don’t do that, you get no provision at all. And then you make no money. So that’s pretty straightforward.

I think that there’s some aspects where the Toronto government could be more modern and more aggressive in that attitude. Because people [developers] make a lot of money. I don’t begrudge them making money, that’s fine. But you’ve got to look at eventually the way it works is it carries on like that. Your key workers, your teachers, might not be living anywhere near the places where they work. And then they have to travel an hour at least or more. And then they’re tired. Everyone pays. And they’re using a car because the transport system here is not good enough. So you know. You make a choice and I think increased density is a very important thing.

Q. With your Yonkers project you’ve said that “you people shouldn’t be afraid of world class architecture†or that was a quote in some article. Now Toronto is very fixated on world-class architecture as a means of redeveloping the city. Do you really think that’s going to have an impact? Like with the Leibeskind Crystal that’s just opened, there’s this hope that it will suddenly launch Toronto into the stratosphere and all of a sudden it will be like London or New York. What do you think of that idea?

A. You’ve got a lot of big buildings here. And you’ve got a lot of crap buildings here. And some interesting buildings. I can get on figures that the mayor’s department told me about the OCAD building, and I don’t know how they calculate this, but it increases tourism 2.3 percent. And if it brings more tourism into the city, well, tourism is part of the economy, and that’s a good thing.

Almost more important than that is if a really interesting or challenging building — I think the ROM looks okay and it’s really interesting and I’m glad that it’s there. And people who live and work in that area, it gives them a sense of joy every day when they pass it. Why would you want to build something bland when you can build something interesting? It’s not always a question of money. OCAD was built with a budget that was originally put there — a pretty ordinary budget. I think the ROM cost a bit more. But that’s another issue.

Q. [Time’s up.] Thanks for your taking time to talk with me.

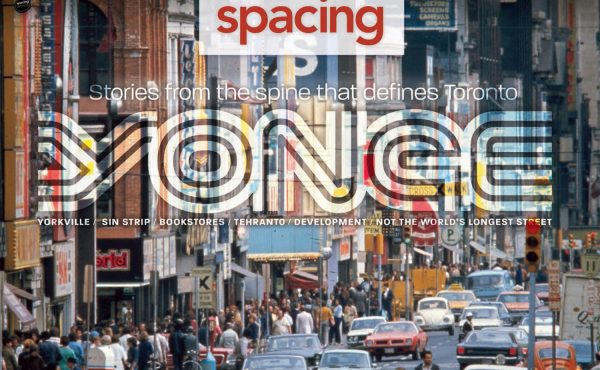

Image (Untitled, 2006) courtesy of Olga Korper Gallery

5 comments

sounds as if you are (an idealist) on the artists side here..me too but…..reality check-.What one must do here is be realistic….stand on the hilltop and look behind you, then turn around and look where you are going…. I am an artist, but not naive. Alsop is right on these points. the evolution of gentrification begins with artists and the counter culture. they inhabit what is viewed as undesirable areas because they are affordable. this is soon followed by cafe’s and antique shops, galleries and small independant concerns. Before long it becomes a destination for those with more income and then they start buying up the buildings and fixing them up and raising the rents…..one cannot stop this evolution……i have seen it in Soho, NYC, the west village of NYC, tribeca of NYC, Chelsea of NYC, Williamsburg, NYC, Dumbo of NYC…also…Newark, NJ, downtown LA, CA….We make areas “cool”. And we will find another area not far from where we are and make it cool as well and the process will begin again….what the artists need to do is form co-operatives from the outset and “rent to own” the buildings when they first move into an area and take the matter into their own hands…. be proactive with forsight,-stand on the hilltop!

Alsop is an artist that happens to be an architect and we should be grateful for his imagination.

Davis, so an affordable units policy, which works in other cities, is not realistic, but artists renting to own, and cooperating even when land prices hit the roof is?

An affordable housing policy is most certainly needed and in place in the cities i mentioned above-not really viable to build them low rise near a city center though.

Again, I think Alsop is right. The evolution will happen so why not make the buildings interesting.

Residents will be displaced, change can be difficult but it is necessary.

cooperatives should be formed early on, before the prices hit the roof.

the “no change” chant coming from artists seems silly to me-same as chanting

‘stagnation”.

Yeah yeah yeah. Toronto is money. The deal is done. Move here to Hamilton and come own historic Victorian buildings downtown with us already. Seriously, check it out. You’ll be surprised.

Thanks for this interview. It reveals how little Alsop really knows about the Queen West Triangle. I wasn’t convinced by his description of his studio practice either.

When Active 18 released their excellent plan for the area at a press conference at Lot 16, I saw Alsop wander in from across the street where he was showing a model suite, and glad-hand whoever was in reach. When the press conference was over, people there crossed the street to view what was on offer, but were forbidden access.

The Active 18 proposal, designed pro bono by a consortium of the city’s leading planners and architects, was imaginative, practical and a model for what the Toronto City Planning Department refers to as vulnerable areas. (They apparently have them marked out on a large map as ‘the next to go’.)

So far as I know Alsop hasn’t been at all interested in working with those most concerned about the future of the Queen West Triangle. His condo plans and bridge proposal are solo, self-aggrandising efforts. Much like his conversation.