Author’s note: I am mixed on the proposed redesign of the Stanley Milner. I believe that there are improvements demonstrated in the new vision including better street interaction along the north front and potential for improved usable green space on the south plaza. However, I do lament the potential loss of the beautiful and comforting concrete pattern that adorns the austere walls. Ideally, would it be possible to preserve certain good design elements of the existing building while improving others?

Edmontonians have become an opinionated bunch when it comes to building design. Take for example the proposed building renovation and new façade for the Stanley Milner Library. People were quite divided. Proponents emphasized its new “iconic” look and the much needed improvement along the north face while others were concerned with losing a landmark that features a cold yet familiar concrete design.

Public figures have also been asked to put in their two cents: a city councilor remarked that the structure is “hideous-looking,” which is similarly echoed by the library director and insinuated throughout an article in the Edmonton Journal. Common language that surfaced from these discussions like “facelift,” “outdated,” and “drab” set an overall negative tone to the existing state of the building.

And here, I worry sometimes that we are not able to distinguish between good design and novelty.

To provide a bit context behind this paranoia of mine, Edmonton has a recent history of poor design throughout the ‘90s that continued onward into the turn of the millennium. With a boom and bust economy where the city population has rapidly shrunk and grown, the city garnered a reputation as a discount town with little long-term investment characterized by cheap box architecture and neglect. During that time, Railtown, City Centre Mall, West Edmonton Mall, and Oliver Square were built without much discussion on aesthetics with complete faith that the amenity itself would be sufficient enough to bring vitality to neighbourhoods.

Presently, Edmontonians have started to speak out against this habit, perhaps best reflected in the former mayor Stephen Mandel’s famous words: “no more crap.” However, that mantra itself is troublesome. The statement isn’t particularly useful since it does not inform people what crap and good design actually are. It also denigrates architectural gems and designs from previous booms that have been neglected and underappreciated. Consequently, there is this attraction to proposals that are new and flashy – supposedly a design that “pops” – whatever that means. The discussion instead focuses on whether or not the design is iconic, new, world-class, cool, modern, massive, or features the demolition or modification of any underperforming building.

A good design, in contrast, can be articulated for its qualities rather than focusing on how it somehow conquered past under achievements. They address their intended functions yet present themselves in a holistic manner while recognizing context. As such, proposals, especially those with a high visual impact on the public sphere, should be discussed and debated from conception. Nothing screams more originality and creativity than a project’s sole raison d’être or justification being because “it’s cool” or “every other city is doing it.” Does this stink of elitism? No, conversely, if the aim of a project is to make a city “iconic” or “world class,” that mentally is just that. Instead, design should come from an actual need since it also has its rewards not just in terms of aesthetics – it should without much debate inspire minds, lift spirits, create wonder, place-make, generate activity, and increase productivity.

Despite the abundance of cheap architecture built in this city, Edmonton, ironically, was once considered architecturally advanced by the end of the 60s well into the 70s thanks to the oil boom. I have colleagues and friends from other Canadian cities that marveled at the sights of our modernist gems including the CN tower and Peter Hemingway Pool. These buildings should be celebrated as part of Edmonton’s story with class. Even if they are deemed as outdated, there is a certain aesthetic of its time that should be appreciated for preservation that helps builds the collective memory of Edmontonians. Any modification should be tasteful to respect the overall aesthetic. Unfortunately, as seen with the additions to the Stanley Miller Library and the Telus World of Science, Edmonton has not been great in respecting that quality.

Peter Hemingway Pool, 1970. Photo by WinterforceMedia.

Peter Hemingway Pool, 1970. Photo by WinterforceMedia.

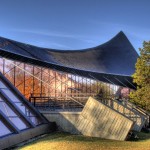

Space and Science Centre, 1984. Photo by Douglas Cardinal Architects.

Space and Science Centre, 1984. Photo by Douglas Cardinal Architects.

Periscopes in front of the AGT Building (Legislature Annex), 1951. Photo by WinterforceMedia.

Periscopes in front of the AGT Building (Legislature Annex), 1951. Photo by WinterforceMedia.

Tory Lecture Theatre. Photo by University of Alberta.

Tory Lecture Theatre. Photo by University of Alberta.

Edmonton Planetarium, 1959. Photo by flickr user striatic, CC BY 2.0.

Edmonton Planetarium, 1959. Photo by flickr user striatic, CC BY 2.0.

CN tower, 1966. Photo by flickr user striatic, CC BY 2.0.

CN tower, 1966. Photo by flickr user striatic, CC BY 2.0.

Crown Plaza Hotel, 1966. Photo by Dave Sutherland CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

Crown Plaza Hotel, 1966. Photo by Dave Sutherland CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

Muttart Conservatory, 1976. Photo by Greg Whistance-Smith

Muttart Conservatory, 1976. Photo by Greg Whistance-Smith

Stanley Engineering Building, 1968. Photo by WinterE229 [http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/User:WinterE229]

Stanley Engineering Building, 1968. Photo by WinterE229 [http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/User:WinterE229]

Northwest Utilities Building, 1957. Photo by James Dow

Northwest Utilities Building, 1957. Photo by James Dow

Not to say that we have been doing a terrible job. Fortunately, there have been a few recent projects that showcase quality design as shown below. However, they are few and rare and the city is still desperately hungry for good architecture. So how can we raise the bar to match the strong visual cultures found in cities like Winnipeg or Montreal?

ArtHub118 Residence and Gallery. Photo via Artshab Edmonton.

ArtHub118 Residence and Gallery. Photo via Artshab Edmonton.

Mill Creek Flex Homes, Battle Lake Design Group. Photo by Larry Wong.

Mill Creek Flex Homes, Battle Lake Design Group. Photo by Larry Wong.

Churchill LRT Station Portal, Shelterbelt Architects (now Group2).

Churchill LRT Station Portal, Shelterbelt Architects (now Group2).

Cambridge Penthouse, Manasc Isaac Architects.

Cambridge Penthouse, Manasc Isaac Architects.

LEVA cafe, WeAreAllConnect Creative Collective. Photo by Paul Giang.

LEVA cafe, WeAreAllConnect Creative Collective. Photo by Paul Giang.

The Cavern, wood interior designed by Oliver Apt.

The Cavern, wood interior designed by Oliver Apt.

Commercial Building on 118 Avenue, Shelterbelt Architects (now Group2)

Commercial Building on 118 Avenue, Shelterbelt Architects (now Group2)

Capital Health Centre, Dub Architects. Photo by Chris Vander Hoek.

Capital Health Centre, Dub Architects. Photo by Chris Vander Hoek.

Jasper Place Library, Hughes Condon Marler and Dub Architects.

Jasper Place Library, Hughes Condon Marler and Dub Architects.

“Have A Nice Day” by Chelsea Boida & Mark Feddes. Photo via Edmonton Arts Council.

“Have A Nice Day” by Chelsea Boida & Mark Feddes. Photo via Edmonton Arts Council.

In the absence of a prominent architecture school or dedicated architecture critics in our mainstream media, the public needs to be both welcoming to bold ideas and highly critical of them at the same time. Rather than focusing on the shiny and new, proponents need to be open to debate and flexible for change. Meanwhile, critics need to provide meaningful and constructive feedback so that better designs can be produced.

So Edmonton, rather than iconic, what does a well-designed library look like?