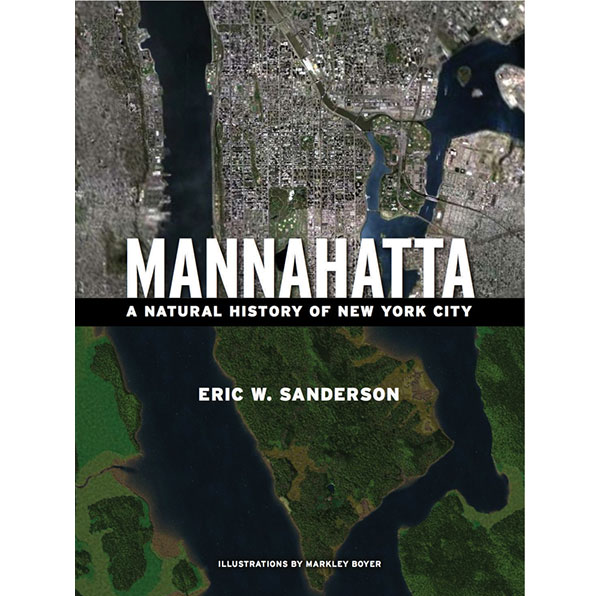

Author: Eric W. Sanderson (Harry N. Abrams, 2013)

Cities are inseparable from their unique landscapes. The values and culture of the earliest settlers are embedded in the terrain they inhabited. As a result, each urban centre is a physical response to those initial conditions.

Unfortunately, our ability to thoroughly gather, understand, store, and share information is a recent phenomenon – making the knowledge of how early landscapes transformed into the metropolitan counterparts virtually impossible to attain. Yet, how wonderful would it be to have the ability to see and understand the landscape of your city before the pavement, cars, and buildings were there. What could we learn? How would this change our appreciation of built and natural environments we inhabit?

Well, that is exactly what landscape ecologist Eric W. Sanderson sought to do for the city he lives in – New York. An ambitious undertaking to say the least…and it is this journey that is wonderfully described in the his book Mannahatta: An Natural History of New York City.

As the printed culmination of nearly a decade of research for the Wildlife Conservation Society‘s Mannahatta Project, the book is an engrossing narrative about the process of piecing together and visually representing the landscape of Manhattan on eve of its birth four hundred years ago – that September day in 1609, when Henry Hudson and his small crew set foot on the island at the mouth of the Hudson River.

In keeping with the simple clarity of the endeavour, the book is broken up into seven well-defined chapters: The Mannahatta Project, A Map Found, The Fundamentals of Mannahatta, The Lenape, Ecological Neighbourhoods, Muir Webs: Connecting the Parts, and Manhattan 2409. Each of which is well endowed with beautiful historic and contemporary pictures.

The most remarkable and provocative imagery, however, are the ones in which high-quality computer simulations of the original landscape they uncovered are contrasted side-by-side against the modern city, shown from the exact same perspective. These are peppered throughout the book and owe their existence to the detailed base information they gathered and complex computer simulation software they used to visualize their data.

As mentioned above, the book narrative weaves together the process of gathering the information they used to create their simulations, as well as the results of their efforts. The content of each chapter gradually builds upon the information of the previous one to create a detailed understanding of this complex landscape.

The first chapter – The Mannahatta Project – does a great job of laying out the framework of the undertaking without going into the depth that is encountered in later chapters. It also explains motivations and goals behind the project and, importantly, puts to rest the typical critique against books of this sort: that Manhattan should be returned to its original primeval state.

To the contrary, Sanderson strongly advocates for the many wonders Manhattan offers as a bustling city. But, in accordance with contemporary urban systems thinking, he also recognizes that New York is an ecological habitat in itself – one that doesn’t work well in many ways.

With this in mind, he explains that The Mannahatta Project is not a nostalgic reflection of the past, but a necessary step to envisioning a brighter future for Manhattan – one that seeks to re-establish the connection to the natural systems that contributed to its current status while maintaining the excitement of the modern metropolis. This underlying theme – explicitly stated within the first chapter – permeates throughout the book, as Sanderson gently draws comparisons between the the original and contemporary landscapes, while ensuring to explain the advantages and disadvantages of each.

The next chapter – A Map Found – describes the story behind the British Headquarters Map, drawn circa 1782-83. Its discovery by Sanderson kick started the Mannahatta Project because it so accurately depicted the topographical and built features of the landscape, at the time of its making. Amazingly, after almost two centuries, the features depicted lay within a mere 49 meters of Manhattan’s modern street grid. As such, it served to produce the main base map on top of which further elaborations were made. A brief historical outline of some of the major events in Manhatten’s history and the creation of the British Headquarters Map, are also included.

The Fundamentals of Mannahatta discusses the essential abiotic factors – topography, bathymetry, and geology – necessary for reconstructing an accurate picture of the flora and fauna in 1609. The interesting story of how they arrived at their topographic elevations is explained, as well as the first glimpse of GIS maps depicting the cities original nature features – streams, watershed, soils, etc. The relationship to the climatic factors in the areas are also touched upon. Continuing the gradual layering of the Mannahatta landscape, the following chapter speaks to the people who inhabited the land – the Lenape.

Although a lot of information of this culture is fragmented, Sanderson offers a “best guess” based on their research. Towards this end, he and his team used the GIS data collected (as well as other archeological documentation) to spatialize the Lenape living environment. This included important information such as where they lived and why, how they moved across the landscape, and seasonal patterns.

Deeply interwoven with the latter, this chapter also describes the role the Lenape had in transforming the landscape and local ecology. In particular, Sanderson maps the most likely locations where anthropogenic fires were created on the island and how they affected the initial perceptions of the landscape by early European settlers, who mistook these manufactured landscapes to be its natural state.

Turning to our other living counterparts, Ecological Neighbourhoods goes into depth about the diversity of the fifty-five ecological communities that peppered the island. Once again, these are mapped out based on data and computer simulation. Given that many of these areas have been severely disrupted or destroyed in present-day Manhattan, the topic is discussed alongside many photos of outside landscapes that speak accurately to how these ecological areas once looked. The discussion of the specifics is wonderfully intermingled with a ecosystem basics that explain, in a very accessible way, the attributes of these different areas and how they work.

The following chapter – Muir Webs: Connecting the Parts – expands on the ecological concepts examined previously through introducing the concept of Muir webs. Named after prominent naturalist and ecological thinker John Muir, the concept speaks to the interdependencies of biotic and abiotic things. This method was ultimately used to develop a comprehensive list of species of flora and fauna in and around Mannahatta.

Given that listing all the species would make for a dry read, the chapter wisely focuses more on explaining the conceptual framework and listing a handful of the most significant elements in the Muirs webs. However, for those interested in the specifics, a very comprehensive list of the flora and fauna is given in the Appendix.

The final chapter – Manhattan 2409 – re-introduces the importance of the modern city and recent development trends that are making their impact on the New York. Within this context, Sanderson discusses food, water, shelter, energy, transportation, and parks. Similar to how the book began, meaningful comparisons are drawn between the methods of the original inhabitants and the current population – gleaning some good lesson and future directions.The chapter ends with a vision of Manhattan four hundred years into the future.

Continuing with the balanced tone of the book, Sanderson puts forth a cautiously optimistic view of how the city will change in light of decreasing resources and climate change. Although the Sanderson’s words will be familiar to those in tune with current urbanism discourse (i.e, growing food locally, diverse multi-modal transportation, etc.), they undermine the boldness of the final image spread contrasting contemporary New York with “Manhattan 2409”.

Using the same advanced visualization techniques to represent the Mannahatta landscape, the future New York is shown with high density nodes sitting amidst vast tracts of the farmland and green space reclaimed from the surrounding boroughs. Manhattan Island proper is shown with its a number of its historically significant streams reintegrated into the urban fabric – several of which are depicted radiating from Central Park.

This is great thought-provoking way to end the book although it would have been that much more powerful had it been decided to move the spread one page over to actually end with the images instead of a couple of pages of text…a small detail. The last one hundred pages are given over a great set of appendices as well as elaborative notes, and bibliography.

Given the scale of the endeavour and the skill with which it was executed, it is difficult to poke too many holes in the book. However, as an outsider, it is important to state Mannahatta is written for a New York savvy audience. That is, since the content of the information is geographically based, there are a lot of references to existing neighbourhoods and local landmarks (Harlem, Washington Heights, Inwood Hills, etc.) that most foreign people would not know without a general map to refer to. This can be a bit disorienting and somewhat frustrating for those who, like me, yearn to know generally where the topics of discussion are located.

Additionally, there are times that the depth of information depicted does not work well with their respective maps. This is particularly evident in the soil and ecological communities maps that are very interesting, but lose their informative power because one can’t really read the subtle differentiation of coloured area due to the small size of the map. Including enlarged map sections that focus on some key areas or providing larger versions of these maps would have spoken more to all the work that went into their making and the thorough information they provide.

But these are small complaints relative to the important contribution of Mannahatta. It deserves all the acclaim it has received for its technological achievement but, more importantly, for the sheer determination and will of its makers who undertook the detective work that led to the beautiful imagery throughout.

Furthermore, although the focus of Mannahatta is geographically specific, the story of New York is really the story of all cities. That Manhattan is an extreme case in terms of its size and economic power makes this work all the more appropriate to learn lessons of urbanization from. One can only hope that Mannahatta will inspire other cities to take the same steps towards gaining the knowledge to secure the future prosperity of their built and natural landscapes.

***

You can get more information on the book here or visit the interactive and informative Mannahatta Project website directly. There is also a good feature and interactive map on the National Geographic website.

**

Erick Villagomez is one of the founding editors at Spacing Vancouver. He is also an educator, independent researcher and designer with personal and professional interests in the urban landscapes. His private practice – Metis Design|Build – is an innovative practice dedicated to a collaborative and ecologically responsible approach to the design and construction of places. You can see more of his artwork on his Visual Thoughts Tumblr.