Rod Robbie is a Canadian architecture legend, but to Caroline, Angus, Karen, and Nicola — the keepers of Rod’s vast archives — he was just a dad with a cool job and a pack-rat tendency.

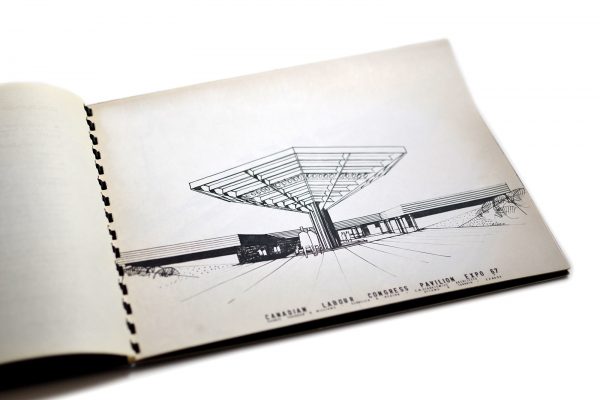

Torontonians are probably familiar with his work on a little ol’ building formerly known as the SkyDome (they even named the pedestrian bridge after him). Though the Dome was considered one of the world’s most innovative buildings at the time of its opening in 1989, unique architecture was old-hat to Robbie. He was part of the design team that created the Canadian Pavilion at Expo 67, an inverted pyramid that is still considered a construction and engineering marvel.

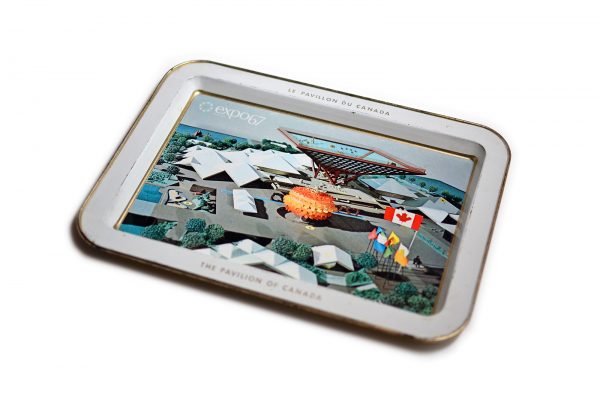

While Robbie was a lover of grandiose design, he was also enamoured with the simple elegance of objects, including a plethora of items collected from Expo 67. His daughter Nicola says, “Archives, visual or written, were very important to my parents. They instilled a sense of history and its value in all of the children. Expo 67 was a seminal period in the history of our family.” Daughter Caroline, herself the Head of Interiors at Quadrangle Architects, has continued the family tradition of collecting keepsakes from the exhibition. “I’ve gone on to find many Expo trinkets in flea markets and vintage stores since the 80s,” she says. “I buy them whenever I see them and now have friends who collect them for me as well.”

In the Fall 2017 edition of Spacing, we ran a lengthy feature on the messy aftermath of Expo 67 that also showcased some of the Expo 67 objects collected by Robbie and his children. Here is a Q&A with about those objects.

LEFT to RIGHT: Adam Vaughan (son of Colin Vaughan: co-architect of the Katimavik); Angus (youngest child, with his children Emmanuelle and Raphael; Karen Hall (nee Robbie); Nicola Robbie; Samantha Robbie-Higgins (daughter of Caroline Robbie); Victoria Bristley (nee Hall, daughter of Karen Hall); Caroline Robbie-Montgomery.

Photo by Craig James White from Urban Toronto

RESPONSES FROM ROBBIE FAMILY

KH = Karen Hall (nee Robbie), eldest daughter

NR = Nicola Robbie, second daughter

CRM = Caroline Robbie-Montgomery, third daughter

AR = Angus Robbie, son

What were you father’s thoughts on Expo 67? Was he happy/proud/excited about Katimavik?

KH: He was ecstatic to get the job and I think he was startled that they beat out the established architects in Canada.

AR: He was extremely proud of Katimivik. He often told me the story of how when he made the presentation to the committee to try and get the job in the first place, that he burst into tears in front of them because he was so emotional about the possibility of even doing such an important job for the country he chose. There is little doubt that it was one of the projects he was most proud of in his career.

What did he think of the rest of the pavilions?

KH: He was impressed by the US pavilion, while also liking and the humor and the roof of the German pavillion. Was very unimpressed by Russia: “boring lump full of tractors.” He also liked the British pavilion but thought they didn’t handle the queues well (the Americans used a snaking line that kept people walking so it didn’t seem such a long time to go in).

NR: I do not know his thoughts other than he tried to make sure that we visited as many of them as possible when we visited the site throughout Expo. As we entered each building he would discuss what he believed the architects were trying to accomplish with the design of the building.

CRM: He talked about how diverse the architecture was. He was always proud of the fact that the Canadian Pavilion was the only site that was on-time. He loved describing the stop-watch process that the construction supervision team used to time concrete trucks leaving the plant and arriving on site to ensure the concrete was optimum for structural strength. Some of the trucks were rejected – maybe the same should have happened at the Olympic Stadium.

AR: He said to me that the American pavilion was okay, but it’s content was great. The Soviet one was brutal, the British itchy, the French ugly.

Did he ever talk about the state of the Expo 67 site from the 1970s and 80s?

KH: I think he was mostly worried about the legal liability of allowing people into the buildings and site for years when the contract was to build a “temporary building” that was only supposed to be used for a few months. He kept mentioning it to me.

CRM: He worked to get the pavilion torn down as the professional liability would have survived his death according to the rules in the 70s and 80s.

AR: My only recollection was basically anger that the Canadian Government did not fulfill their agreement and instead sold the site and buildings to the Quebec government for a $1. His concern was that the pavilion was never designed to be permanent and he had liability. So it was, after years in the mid-1970s becoming a safety hazard and legal proceedings were initiated to have it demolished. By the 80s the building had been demolished, the site had been transformed, and had become a part of the new F1 racetrack.

Why did he collect these Expo 67 items? Why did you keep them after he passed away?

KH: I think he wanted us to realize that anyone can have a good idea, but you have to be persistent to get it out into real life. The ashtray was a start, but he and his partners had to make it a huge building. We kept them because they are part of the story about how they got the contract and they remind us of him, even if some of us were very young at the time.

NR: Both my parents (mother was Enid) believed in preserving history. Archives, visual or written, were very important to both of them. They instilled that sense of history and its value in all of us. Expo 67 was seminal period in the history of our family. It embodied the 60s for us.

CRM: I’ve gone on to find many Expo trinkets in flea markets and vintage stores since the 80s. I buy them whenever I see them and now have friends who collect them for me as well.

AR: He was quite sentimental and most definitely a bit of a pack-rat. He kept many souvenirs of things that were important to him and Expo 67 most certainly fit into that category. We kept them because they were so important to him, and it is interesting to both see what the country felt about the event and building, but also to honour his memory.

What do these objects say to you about Expo?

KH: It was a moment for Canada to shine in front of the rest of the world. That’s why he insisted that Canada have the biggest and best site and largest (or close to it) pavilion. It surprises me how many people who went to it remember that visit decades later — it matters to them, sort of like Canadian version of someone who actually went to the Woodstock concert.

NR: Not speaking of the objects, but rather the history of the design process, the design team for Canadian Pavilion was made up of a group of immigrant architects, (who had been in the country less than 10 years). With the current discussion going on about the role and value of immigrants to Canada, they exemplified the value immigrants can bring to their adopted country. To me, the statement about hope and wonder for the future still resonates today. The anthem played in the Ontario pavilion has been re-worked for the Province of Ontario to celebrate the 150th anniversary. It still evokes an emotional response from me when I hear it.

CRM: The objects my father saved are particularly special as they remind me not only of the fun that Expo represented to me as a 6 year-old but also of my Dad. He would talk about what the fair represented on so many levels – architectural excellence and exuberance, a country that gives its most important commission to a bunch of 30-something immigrants, showing the world that Canada was an inclusive mosaic instead of a melting pot. He was so extraordinarily proud of having contributed to that moment in our collective history.

AR: I was too small to attend and do not remember the building on a personal level. However, it’s clear that Expo 67 redefined Canada nationally and internationally. It destroyed the stereotype that Canada was a subject of England or a little cousin of the US. It helped us shape our own cultural definitions and engender a national pride that had been lacking.

What do you think architects/planners/designer can learn from Expo 67 50 years on from the event?

KH: Don’t think small, think big, and be clear what the point of the building is. Make some part of it on a human scale, and make sure there are interesting things to look at (not just a massive tower or lump with no details). Don’t be afraid to be non-conventional.

CRM: Like Karen says – don’t think small. Architecture and world fairs can become so much more than a physical site and period of time. They can define a country and generation if they are done right.

NR: Capturing the emotional centre of an event is crucial to ensure that it becomes an indelible part of the fabric of the specific place and time.

AR: They can learn that risk in design is essential if iconic results are the goal. That you don’t get anywhere if you don’t ask. That seeking work and winning jobs can sometimes be about the emotional commitment you show the customer, even more than a design concept. When Dad won the Katimivik bid there were no designs, just a dedication to Canada from a group of young immigrants who wanted to say thank you to the country they had adopted and loved so much.

photos by Matthew Blackett

One comment

Those in Toronto can further bring experience this era of inspiration and construction by visiting the gallery within Ryerson’s architecture building: http://www.arch.ryerson.ca/phc-gallery/exhibitions/#architecture-and-national-identity-the-centennial-projects-50-years-on