“The fascination of architecture in extreme environments is that it is so demanding technically, yet offers so much potential… the greatest constraint usually comes from the need not to spoil the natural environment, and that demands more judgment than the need to match the brickwork of an adjoining building.”

– From the book’s introduction

Editor: Ruth Slavid (Laurence King Publishing, 2009)

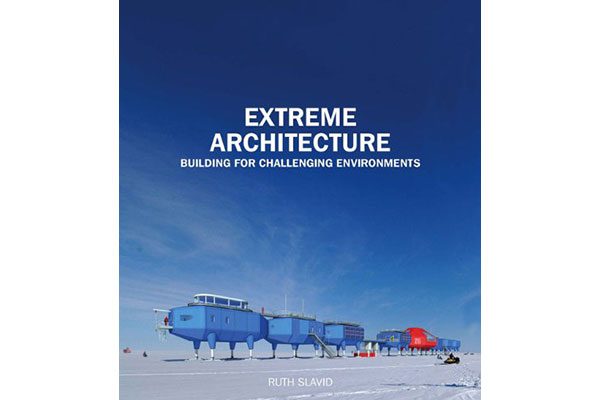

As we presently hear more and more each day about the environment and what design professionals can do to turn the tide on total systemic collapse, it may do us well to ponder the extreme scenarios that a designer could face, whether in a Kalahari summer or an Antarctic winter. Author and editor Ruth Slavid gives us forty-five instances of just such designs, along with their designers in Extreme Architecture, a formidable 208-page volume containing 296 awe-inspiring images of these ‘extreme’ visions.

As presented in five categories – Hot, Cold, High, Wet, and Space – the editor features projects from all around the globe in as many different extreme sites, by the likes of Sir Norman Foster, Zaha Hadid, and Mario Botta, with more familiar and closer to home projects by Seattle-based Tom Kundig and Vancouver-based Hotson Bakker Boniface Haden.

As a point of departure, the book’s introduction proposes the most extreme of ‘extreme architecture’ – a spaceport in New Mexico for Virgin Group owner Sir Richard Branson, providing a terminal for those who can afford the $200,000 ticket to take a ride in space. As the book’s editor explains it, the building is both a means to an end for traveling through the extreme environment of space, as well as requiring to be able to withstand the extreme temperatures in the New Mexico desert. Sir Norman Foster’s project in Abu Dhabi also inhabits a desert, with his solution being a city with a zero carbon output.

And so the first section of the book–Hot–opens with Masdar, a proposal to create a small town off the grid, producing zero waste and no carbon footprint in the desert (kind of Archigram meets Burning Man). With global warming and the rising temperatures an everyday subject now, it is no surprise that the first fifty pages of the book are dedicated to the subject of heat, with extreme examples from Arizona, the Canary Islands, Abu Dhabi, Australia, and even the interior of British Columbia. The editor makes the poignant observation that it is the air conditioner that has single-handedly been responsible for the existence of Dubai and Abu Dhabi, much like the tall buildings of New York and Chicago depended on Otis’ invention of the elevator.

But of all ten of the projects featured in this chapter, it is in a school in Burkina Faso that best demonstrates the editor’s intent to show work that represents humanity overcoming the perils of their environments, whether through climate-change or a catastrophic seismic event. In the case of Burkina Faso, this is portrayed by the architect Diebedo Francis Kere.

Born in Gando, a village in Burkina Faso, Kere went to architecture school in Berlin, then returned to his country to build better schools and infrastructure, using design to create healthier buildings, and not necessarily adopting solutions from the West. He set up a fund while in Berlin to build a school back home, and the resulting building is an ingenious display of local materials and craftsmanship married to a modern sensibility about environmental design. The editor points out how simply using cross ventilation, Kere’s buildings created comfortable environments without the need for HVAC, though by Western standards the environments would probably still seem to be warm.

Another of the ten projects representing Hot is the Nk’Mip Desert Centre in Osoyoos, given the area’s arid conditions. An award-winning facility by Hotson Bakker Boniface Haden + Urbanistes, its sustainability includes its use of a massive earth rammed wall to insulate the centre from the desert’s summer heat. Intended as a demonstration centre for sustainable principles, the rammed wall and landscaping serve to show that a building can be restored to its environment by clever camouflage, where the landscaped artifact becomes an artificial landscape.

The second section of the book–Cold–looks at architectural design and its relation to winter conditions, whether the doldrums of the winters in our northern hemisphere or the technically savvy science facilities in Antarctica. ‘Cold’ is represented with an odd cross-section of winter habitations, from single habitations in the winter landscape such as Tom Kundig’s Delta Shelter in Washington, to survey station modules in the Antarctic, the stunning photography of which provides the image for the book’s cover. The editor also features a storage facility in Norway–a seed ark–as well as various designs of ice hotels and bars by designers from Canada, the UK, and Sweden.

There are two projects in Cold which represent the two poles of the editor’s intent to show extreme architecture in this category. The first is the Abisko Ark Hotel in Sweden, the setting for which provides the clearest skies year-round to view the aurora borealis, as well as the option of modern fishing shacks from which to ice fish. This facility, for which the clientele spends large sums of money to spend one night on the edge of the Arctic Circle, is in stark contrast to the second project—the Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station—which is a scientific research outpost where luxury is forsaken for necessity. Not unlike building a space station in outer space, the South Pole Station could not be further removed from the extreme tourism industry, which—along with ice hotels and posh ski-chalets—has necessitated creating architecture at higher elevations, the subject of the next chapter.

The introduction to High, the book’s third section, gives a brief history of mountaineering, and how this 18th-century pastime in the Alps has ballooned into an industry of winter sports the world over. Most certainly we in Canada are aware of the industry of skiing and snowboarding, as well as the infrastructure necessary to get the winter hedonist to their final destination, as represented by the Carmenna Chairlift Stations in Arosa, Switzerland and Galzigbahn in Austria. Competitive ski jumping has also provided the impetus for much in this chapter, as represented by the breathtaking Garmisch-Partenkirchen in Germany. Slavid rounds out the chapter with an airship, as it represents now (as it has in the past) a new height of extreme architecture.

The two standouts in ‘High’ however are unquestionably the Nordpark Cable Railway by Zaha Hadid Architects and the Aurland Lookout in Norway. Both have received much praise and have been widely published: the former for its expressive and bold forms which frame the 1.8 kilometer cable car ride from Innsbruck to a nearby mountaintop, the latter for its daring engineering to thrust the observer away from the earth to become a part of the scenography itself.

It is curious to point out that while parts of ‘Hot’ and ‘Cold’ involve extreme architecture for maintaining human comfort and survival, ‘High’ is simply about recreation, whether looking at a majestic view or partaking in a winter sport. Certainly, there is no better example than Mario Botta’s Tshuggen Bergoase Spa as an example of a building that finds itself on the edge of civilization with its need to offer its clientele an escape from the world.

The fourth section of the book—Wet—is like ‘Hot’, both of which concern to the world as they relate to climate change. Anyone who has been to Venice knows that sea levels are rising at an alarming rate. So, much of Slavid’s selection deals with this issue. While she points out that Katrina was a wake-up call for the US in 2005, the Dutch have had to deal with flooding in urban areas since time immemorial, as 27 percent of its land is below sea level. The first five selected examples of wet architecture are hence floating houses, including a floating sauna, with a floating cruise ship terminal rounding out the bunch.

But recreation make an appearance in this category, yet again, as the palm tree developments in Dubai create a desire to be near the water’s edge despite rising sea levels. And going one step further, underwater hotels have taken architecture to the extreme, as Dubai boasts one, as well as Fiji as represented by the Poseidon Underwater Hotel. The rigours of designing an underwater structure, while most certainly taking on the guise of naval architecture, is only a hop-skip-and-jump to the concept-soon-to-be-reality Seaorbiter by Jacques Rougerie Architecte. A structure that the Slavid likens to something from a Jules Verne adventure, this diver’s platform and research station will be half-above and half-below the ocean’s surface.

Such an extreme architecture as the Poseidon Hotel and Seaorbiter provide the perfect setting off point for the final category in the book—Space. Given the same necessity of space restrictions for human comfort and off-grid self-sustainability, living in space has for the most part remained the stuff of science fiction. But with the reality of the aforementioned Spaceport America in New Mexico, one can only imagine the next wave as being spending a weekend on the moon. The extreme architecture making up this final chapter certainly makes it seem possible, as habitations and vehicles that are not necessarily tailored to NASA’s out-of-this-world budget become one step closer to reality by design. And Arthur C. Clarke would smile to see the Galactic Suite, which as envisioned by Barcelona architect Xavier Claramunt is a scene right out of 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Overall, Extreme Architecture is an exhibition of humanity’s daring—and at times hubristic—preoccupation with living on the edge and inhabiting those places that we would be better to avoid architecturally. But existing uneasily in the background is the notion that some of these intolerable sites for our buildings may become reality, as sea levels and temperatures rise. The book would have certainly benefited from having an essay that could’ve spoken of the polar human activities of survival, such as after a catastrophic weather event, and hedonism, as represented by so much of the recreational architecture in the book. Otherwise, the book is a thought-provoking look at some of architecture’s more curious designs, collected by the editor of such other Laurence King publications as Wood Architecture (2005) and Micro (2007).

***

Originally published January 26, 2010.

***

Sean Ruthen is a Metro Vancouver-based architect and writer.

One comment

This seems like a book I want to get my hands on. Or, failing that, my local library’s hands. Particularly from a designer’s POV.