Cross-posted from No Mean City, Alex’s personal blog on architecture

![]()

There are very few galleries in Toronto – or anywhere – that focus on presenting architectural ideas, so I’m always happy to see a new show at Harbourfront‘s Architecture at York Quay Centre. Building Partners, which runs through the end of the year, is typical for this venue: it’s got a smart, engaging idea and explores the full range of what an architecture show can be. For better and, this time, for worse.

First, to the good. The exhibition invites three architectural firms, Moriyama & Teshima, Ian MacDonald Architect and Dubbeldam Design Architects, along with glass artist Jeff Goodman, to answer an interesting set of questions. “What is the relationship between architect and client? Is building a compromise or a collaboration? Can the client/architect relationship lead to a better building?”

This theme cries out for some kind of interactivity, and Dubbeldam – alone among the four exhibitors – actually delivers.

Their installation, titled pull.push.slide.pivot.lift.turn, is an adventure playground of white planes, fuzzy walls and colourful felt cubes. To get into the space, you need to choose between two doorways. To the right, there’s a corner lined on all sides with felt. To the left leads you into the main space, where you can play with those felt boxes – they’re bright orange – to build your own abstract composition or assemble a loveseat. To the back of the room, a light installation turns off and on as you slide a wall panel along a track; in one corner, a pivoting wall with a slot window lets you create various views across the space and toward a strategically placed mirror. (Click for larger images.)

Here’s a plan of the space – which is about 13′ by 18′ – with some of the many ways it can be rearranged:

It’s fun. And what does it signify? The architects’ statement suggests that as users move the elements around, they act out the working relationship between architect and client. “Every interaction introduces change and impacts connected spaces within the framework of the architect’s design.”

In an interview, Dubbeldam tells me she’s satisfied how that metaphor has been playing out: visitors to the exhibition have in fact made it their own, sometimes in surprising ways. “Once, we found the cubes crammed together up to the ceiling,” she says. “I’m not even sure how they got up there. We had to get a ladder to pull them down. And another time, we found the cubes stacked up in two tall columns outside the space.”

Okay, but that’s not exactly what most construction sites look like. It’s designers and contractors who typically move walls around. Dubbeldam’s response is interesting: “We have controlled every single response – or 90 per cent of them, anyway,” she says. “It’s the same as when we present a client with options, which we always do in our practice. They always have a choice, but we only present them with things we like; without that, you don’t have a sense of continuity across the space.”

In other words, as I swung those walls and made skyscrapers out of foam blocks, I was playing their game. As for stacking the blocks in the hall, well, that’s probably not the best move, and sometimes designers need to talk clients out of bad ideas.

This room is ambitious, and it works well. Like the annual shows at the Serpentine Gallery in London, it is a work of design in itself that has something to say.

The other parts of the exhibition include a display of handsome glass by Jeff Goodman Studio – which shows that studio’s work for lighting and architectural installations – and two disappointing rooms of architecture displays by Moriyama + Teshima and Ian MacDonald.

Those two struggle with the basic problem of how to show architecture. The architecture exhibition is a new genre; such displays were rare until the 1960s. Since then, the most common route has to display records of a project – photographs, plans and section drawings. But such displays don’t always communicate ideas well, and they can’t communicate the experience of being in a place.

In the Harbourfront show, there are some remarkable works of architecture to talk about. With Moriyama + Teshima it’s the University of Toronto’s Multi-Faith Centre, which I wrote about enthusiastically a couple of years ago for the New York magazine Metropolis.

Here, the grand idea of that project – to create a vessel of transcendent beauty that can encourage all genres of prayer – gets reduced into sound bites. There’s a slideshow of happy users of the space, audio recordings of their words about it, which are interesting but say nothing meaningful about the design. A panel of lovely onyx stone sits in the corner, looking bored.

Oh, yes, and you get to the slideshow by walking down a path of fine gravel and around a rank of leafy plants. Which means… what, exactly? The space has a tossed-off quality that has nothing in common with MTA’s actual buildings these days, which are smart, finely detailed and at times very beautiful.

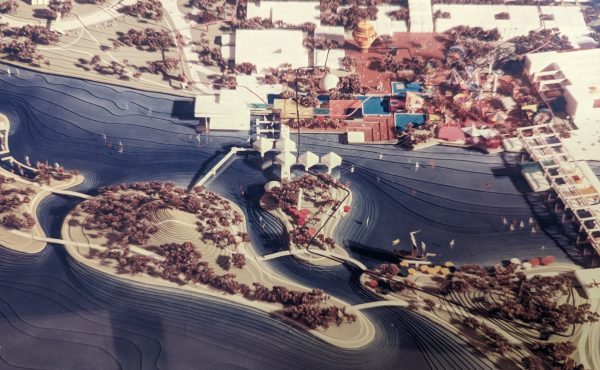

Ian MacDonald takes an even more disappointing tack: his room fully embraces the Pictures and Models On The Wall school. Several of his office’s recent works, all of them fine, show up here as collections of photos and the odd wooden massing model.

This is a photo (by Michael Awad) of MacDonald’s own home in the Wychwood Park district.

And if you’ve seen this, you’ve seen a good chunk of the show. There are some mildly revealing texts about the sites and the ideas that shaped these houses, but nothing essential, and the image panels aren’t visually compelling. The photos aren’t even very big. Stick it all in a book, even on a website, and you’d lose very little.

Which is an uninspiring thought. Take a good, inventive team of architects like MacDonald’s, let them design a room, and they come up with a space that’s hardly worth visiting?

I’m sure there are excuses to be made. No doubt Harbourfront pays very little for these displays, and these offices have more important work to do on actual buildings. But then, why even show up? This gallery is working to show the general public what architects do and why it matters. Boring people is not an ideal way to represent your profession.

Thankfully, the Dubbeldam exhibition is worth a visit on its own. Step right in, and don’t forget to look at all those pictures and slides on your way out.

One comment

I couldn’t agree more with your comment “Stick it all in a book, even on a website, and you’d lose very little.” I’ve found this to be true of most of the architecture exhibits I’ve been to in Toronto (e.g., the “Unbuilt Toronto” exhibit at the ROM, the U of T architecture school exhibits at last year’s Nuit Blanche, other at the Harbourfront Centre). I just don’t get it!