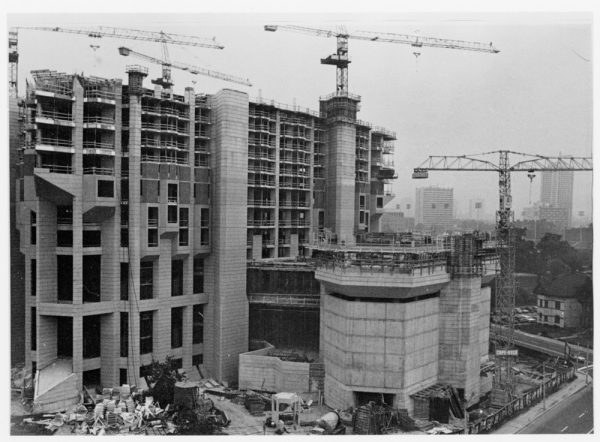

When the University of Toronto’s John P. Robarts Research Library, located at St. George and Harbord streets, opened its doors in 1973, it was the largest academic library building in the world, covering 1,036,000 square feet, housing nearly 3 million volumes and providing space for 4,100 users. Even then, its Brutalist raw concrete aesthetic, massive size, and unusual triangular design was considered controversial. Dubbed “Fort Book” at the time it opened, and in 2019 nominated on social media as the ugliest building in Toronto by readers of the Toronto Star, the fortress-like Robarts Library has evoked strong reactions in anyone who has encountered it.

In addition to providing books and a place to study for countless U of T students, faculty, and other researchers, Robarts Library has made its presence felt in the city of Toronto and the pop culture landscape. Renowned Italian novelist and academic Umberto Eco’s labyrinthine library in his novel The Name of the Rose was inspired in part by Robarts Library, where he spent time in the late 1970s. In the 2000s, Robarts Library was reimagined as a zombie-infested prison in Paul W.S. Anderson’s Resident Evil: Afterlife, and the library even made a brief appearance as a hospital in an episode of the television series Friends.

In 1997 Robarts Library was added to the Architectural Conservancy of Ontario’s Heritage Register, and in 2016 the library was listed as a must-see destination for design buffs with its appearance in Monocle’s travel guidebook to Toronto.

As Robarts Library celebrates its 50th anniversary (see the digital exhibition), architecture, urban, and library experts were interviewed as part of a Robarts Library oral history project. Participants discussed the evolution of Robarts Library and its place in Toronto’s urban landscape, including how critics and design aficionados have pushed for a reappraisal of Robarts Library, making the case for a better appreciation of its architectural and cultural value. Interview excerpts have been edited for clarity and length.

How did Robarts come to be a Brutalist building?

Mary Louise Lobsinger (Mary Lou is a Toronto-based architectural historian, artist, and architect and Associate Professor, University of Toronto, John H. Daniels Faculty of Architecture, Landscape and Design):

There’s a lot of university-related building in the 60s and 70s — it’s really rapid around the world. We see new universities being built in the UK, the US, and in Canada, all in order to deal with the population increase — it’s what we now called the “boomer” generation entering universities. Existing universities needed more space and they had to build really quickly. One reason to use concrete – it’s just really fast to build with, and at that time, not so expensive. And, a building like a library has got to be robust. In terms of use, they need to make sure that it lasts, right? If it’s good quality concrete, it’s not going to fall apart like wood or steel, which would be banged up and still be expensive. So, it has to be sturdy. There are a lot of people coming in and out of these buildings.

Michael McClelland (Michael is an architect and founding Principal of ERA Architects, specializing in heritage conservation, heritage planning, and urban design):

At the time, there was great enthusiasm for constructing big buildings, and there was enthusiasm for concrete. It sounds odd, but you have to think of this type of building within the context of the time, because pre-World War II, if you wanted to build an impressive building, it had to be granite and marble, or sandstone and limestone, as a way to impress everyone with the materials. But after the war, there became a real recognition that we had to build a lot. And concrete became this signal of modernity. It was, in a great way, an equalizer. It was something that was extremely plastic and extremely modern, and the sense of it was very democratic. And so, it became a big signal for university buildings to consider concrete as the material because it showed we were exploring new opportunities, new options, new ideas in materials that could do things that the previous noble materials weren’t able to do. It also expressed a kind of egalitarianism. By using concrete, we’re not trying to look better than anyone else, we’re actually trying to accommodate many, many things.

Shawn Micallef (Shawn is a weekly columnist with the Toronto Star, co-founder of Spacing magazine, and an instructor at the University of Toronto):

I associate Brutalism with a really expansive time in the civic life of Canada, when we were building public institutions. Brutalism was often used for public buildings, university buildings, that sort of thing. So, Robarts Library has this kind of really expansive feeling. It’s like we as a country have a commitment; we are investing in the future by building something so solid. So, there are some romantic notions in my mind about that.

Gary McCluskie (Gary is a Principal architect at Diamond Schmitt, and he led the renovations for Robarts Library and the design of the Robarts Common addition):

The interior, broadly speaking, is extremely well built and well designed, and well detailed. The terrazzo floors, 50 years on, that is a kind of character that not many buildings have, which is impressive and admirable. One of the interior’s really strong features is the glazing, the bronze, the leather wrapped doors, and some of the wood paneling. All those details show that Robarts was well considered and well designed and has lasted very well. So those are admirable qualities.

What do you think of the form and aesthetic qualities of Robarts?

Gary McCluskie:

The architectural expression of the exterior always got loaded in with the “Fort Book” name, and the scale and the Brutalism of the building, but I think it always has had a kind of a rugged, expressive character. Ruggedly handsome, you know? I don’t think anyone would ever use the word “beautiful’” but not everything should be. So, I think it has a very expressive and a very well-designed communication of its composition. I think there’s a clarity to it, the exterior, that makes all those sorts of slightly qualified (but proven) words really appropriate.

Michael McClelland:

I think I was just amazed at the scale and the triangular shape motif that goes through the entire building. It kind of reminded me of Piranesi (the Italian artist), a little bit. Piranesi draws these very mysterious, slightly scary forms and shapes, and this had a level of that. It was a place you could definitely get lost in. And, it had a scale which was hard to appreciate. Because where else in Toronto do you find a scale like that? Which floor am I on? How did I get here? This looks like the other floor I was on. There’s a sense of almost being lost.

Shawn Micallef:

I was always a fan of Brutalism. And I think that a little bit of that is nostalgia. As a kid born in the 70s, you are sort of born into this Brutalist world, at the height of Brutalism.

Why does Robarts get so much hate?

Carole Moore (Carole was the Chief Librarian of the University of Toronto Libraries from 1986 to 2011. She started her career at the U of T Libraries in 1968 and attended the groundbreaking of Robarts Library):

Once it was actually built, I can see some of the problems with the architecture. I think the major one was the issue of accessibility for everybody. The staircases were awkward from the beginning for everyone and really, really difficult for people in wheelchairs or with disabilities. Also what became apparent – and I don’t think it was appreciated – that the wind tunnel effect on that site was just not foreseen, it was definitely a problem. But, many people had suggested to me that the architects were more thinking of the stature of the building and a grand building, than about the people entering it.

Gary McCluskie:

I think the fundamental challenge is the triangular form of the building. It confounds you, upon first entering and learning to navigate the building. I think as people who have a language of understanding interior spaces from the world when we are born, our culture works with rooms that have four sides to them… that central idea that every year, every September, a quarter of the users have never been here before. And you’re introducing them to a building that is missing a corner. And yet they need to find their way around that.

Shawn Micallef:

It’s notorious that students don’t like it, but I think if you talk to students at most universities about their university library, they dislike it. It’s this place of misery, because you’re cramming for exams, and you’re tired and worn out. Or maybe you forgot to write a paper and you’re jamming it in the night before. So, there’s all this kind of stress tied up with the university library. So maybe it’s a little rude to say, but don’t trust students’ opinions on their university library wherever it is, because they have a biased, possibly negative feeling towards it.

David Smith (David is a University of Toronto Professor Emeritus in French Literature, and had an office in Robarts at the time of its opening):

On a practical level, the triangular design does not seem to me ideal for a library. It obviously wastes space, if only because the corners are very hard to use, and it makes things difficult when you build an extension onto a triangle. Moreover, I remember when I first used the stacks, I would come out of the elevator and wander around, trying to find my book on the shelf. I would find it without too much trouble, but then I wouldn’t have the foggiest idea where the elevator was, and I had to go back one way or the other until I sort of bumped into it. Orienting yourself within the stacks requires a lot of experience before you know almost instinctively where the elevator is. My colleagues and I felt much the same – with a certain indifference to the architecture. We were getting a new library, and we were so overjoyed about that, that its architecture didn’t really matter. In other words, we felt that we were lucky to have it but some of the criticisms were made from the beginning and as I say, are still valid.

How does Robarts fit into the university and the city?

Mary Louise Lobsinger:

I think there were many broad assumptions about what a library should be, and what the library represented culturally, within a university and also within the bigger world – the knowledge bearer of the world. A library should have that kind of stature, respect and monumentality, and Robarts just doesn’t look like any of our traditional perceptions of that, right? It doesn’t have the cloisters of Massey College. This is not like Oxford. But we are no longer in that era – we are not Oxford. Something in the 1960s was changing – our demographics were changing. The world was opening up and more and more people from all sorts of backgrounds were going to university. But I think it was significant, again, that Robarts doesn’t really represent the traditional perceptions of academia. So, it probably annoys people that it doesn’t represent “officially” this kind of traditional stature in the university. And certainly, when it was built most of the people writing about the library were men, it was their own specific idea of what they thought they should be living in and building in Toronto, and what Toronto should be like. But Toronto was already changing at that time. Maybe it was a fear of something slipping away…

Francisco Fernando-Granados (Francisco is a Guatemalan-born, Toronto-based professor, artist, and writer):

At the time, Robarts felt like a kind of architectural intervention into the logic of the university, and into the sort of [traditional] neoclassical architectural logic of the university. And again, I’m not sure that I would have necessarily thought that explicitly at the time I first saw it, but when I look back it feels to me like, even architecturally, Robarts signals a different way of thinking about space, a different way of thinking about the city.

Shawn Micallef:

If you see pictures of Toronto, when City Hall opened in 1965, everything was kind of low and Victorian. There were a few little modern buildings here and there. And then you had this literal spaceship-looking building kind of plunked in the middle. Toronto was a small town. It wasn’t this big glass and steel city that it is today – it was getting there. I think if you could put yourself back 50 years, it’d be a bit of a shock at how low and old the City seemed. And so Robarts must have been as striking a skyline addition as New City Hall and the TD Centre when they went up. Especially for people who went to the campus every day, Robarts would be the tallest biggest thing around. So, I think Robarts definitely represents this really explosive growth moment in Toronto.

Gary McCluskie:

I have aerial photographs of the campus from that early 70s era when Robarts was first built, and it’s like Chartres cathedral in the middle of campus. Yet, it didn’t take 100 years to build – we didn’t have time to get used to it as it was going up. It lands over a couple of years and clearly is having a big impact. Now, I think the university – and Robarts – has grown, and the city has grown around it. Although the Library is still imposing in its scale, the city has grown in a way that Robarts now fits in. I think its scale has kind of come of age.

Michael McClelland:

Robarts was ahead of its time for sure. I can relate to and am very sympathetic to the neighbourhood and the kind of blockbusting that the university was doing – which was an inappropriate thing – when it was constructed. But now, we’re getting other buildings of similar scale in Toronto – it’s not like Robarts is all on its own anymore. It’s like the TD Center was the first thing to happen at that kind of scale, and now you can barely spot the TD Center in the downtown core.

Shawn Micallef:

There is such a critical mass of people here now that spaces like Robarts are going to become even more valuable, just as a place to be. Robarts is not going anywhere because it’s built like a mountain. It’s like the mountain at Canada’s Wonderland – the big concrete thing in the middle. I think its spiritual position on the Toronto landscape is going to be as important as it ever was, if not more important.

One comment

I’ve always been quite fond of the building; from the right spot on St. George it looks like an enormous, concrete peacock. From other spots, it looks like an alien embassy dropped onto a Toronto street. And really, the elevators are not at all hard to find; they are always right where you left them 🙂