WHAT: Release party for Spacing’s summer 2013 (Toronto edition)

WHEN: Tuesday, June 25th, 7:30pm-2:00am

WHERE: The 3030 Bar, 3030 Dundas St. West (@ High Park Ave) in The Junction

COST: $8 (gets you copy of mag)

RSVP: Feel free to RSVP on our Facebook listing

MUSIC: DJ Shirley Tempo

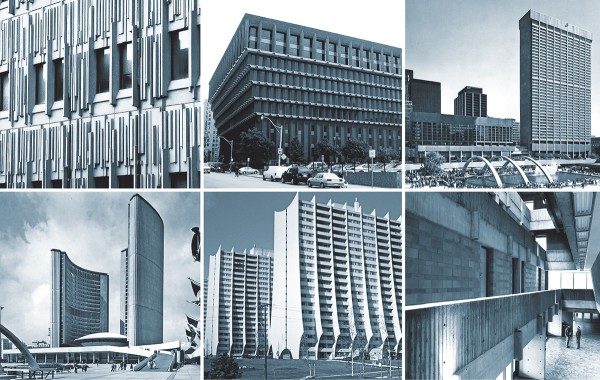

The post-war era defines most of the architecture in Toronto — it’s about time we finally started to appreciate it. And you can do that by showing up to our 28th release party to get your hands on a copy of our newest issue.

In the Summer 2013 issue, our contributors explore a variety of topics related to Modernism and its affects on Toronto’s urban landscape. As Senior Editor Shawn Micallef writes in his essay on Toronto’s mod architecture, “To stand in the middle of Nathan Phillips Square today, after its recent renovation, is to realize how all of Toronto’s Modernism should be treated…. This is how all buildings — the old and not-so-old ones — should be revered: with love, a facelift every couple decades, and some new accessories that give a nod to the contemporary but maintain the building’s inherent style. Yet many Modernist structures in Toronto don’t get this treatment. So much has been left to crumble and fill with debris. The details that made modern spaces and buildings space-age-fantastic have been untended: artfully placed recessed lighting has been left burnt out or smashed in, and extinct fountains are now dry pits collecting detritus. As well, thousands of exquisite Modernist bungalows on residential streets — the era’s equivalent of bay-and-gable Victorians — go unnoticed by most. It’s no wonder Modernism is not universally loved.”

Staff writer Graeme Bayliss examines how churches and synagogues abandoned traditional design and embraced Modernism to attract new believers. Bayliss writes, “The shift from traditional Western religious architecture, with its elaborate ornamentation and utilization of expensive materials, to the generally simple and unadorned Modernist style was not precipitated merely by a change in architectural vogue — after all, when it comes to cultural trends, the sensitivity meter of religious institutions typically operates on a delay of decades. Rather, it was part of a concerted push by religious leaders to shed their elitist image and demystify their practices.”

Thomas Wickes looks at how Etobicoke’s growth coincided with the building boom of the post-war era. This meant everything from residential homes to medical centres to gas stations were built in the Modernist aesthetic. He writes, “Today, these areas such as Etobicoke and North York or Scarborough are often dismissed because they don’t impart an ideal sense of place. In fact, they’ve left a legacy we’re still struggling to deal with: low density, poor transit, and a lack of amenities. For better or worse, Etobicoke’s post-war neighbourhoods have come to define these dilemmas. While it would be a stretch to say that all architecture from the mid-century era is of a fine calibre, that doesn’t mean there aren’t worthwhile discoveries to be made. You just have to know where to look.”

Some of the other features you’ll find in the summer 2013 issue:

- Sam Javanrouh, Toronto’s most popular photoblogger, is retiring his web site Daily Dose of Imagery this summer after 10 years of posting a photo every single day without interruption.

- Senior editor John Lorinc explores how the City of Toronto and other municipalities are experimenting with new ways of reaching out to local residents during public consultation initiatives.

- Erica Simmons casts her eyes back over 100 years to when “child savers” crusaded by creating such forward-thinking projects as playgrounds. At the time, this was revolutionary and constituted a grand social experiment by the local level of government.

- Graphic artist Marc Ngui was challenged by Spacing editors: if Toronto had it’s own currency what would it look like? Whose image would appear on the bills and coins? His results are one of the most unique visual contributions to the magazine in years.

- Spacing was a partner in the Green Line design competition — we highlight the winners and finalists from this great initiative

- Map artist Andrew Alfred Duggan has created a map of Toronto’s bike lanes and trails that will surely become an essential piece of mapping for the local bike riders

If you do not subscribe to the magazine, you can sign up on our online store now and receive 40% off newsstand prices. It’ll be delivered right to your home or office. And nothing better supports Spacing than having a large, dedicated group of subscribers.

5 comments

that was my medical centre as a kid, loved it. a funny old buliding, sad how it’s been neglected.

My biggest critique of modernist architecture is that to me much of it is void of a human experience. While at the time it may have provided a breath of fresh air from excessive ornamentation, today the clean cut design is bland and in some cases even oppressive to the human scale. Much of it is meant to be looked at through pictures, but does not do well to experience in day to day life.

A good example of this is old industry. I was watching an old Stallone movie from the 1970s called FIST, which takes place in the 1930s and is about the forming of unions. Say what you will about the labour practices, but the architecture and the design of these old factories seemed far more welcoming than what you may find in today’s modern industrial parks.

This isn’t to say that all modernism is bad, or that all pre-modern is good however. The subway stations in Montreal provide some brilliant examples of modern art, while Union Station commits many of the sins of modernism (looks fantastic in pictures and far away, but feels oppressive and makes one feel small when walking against its walls along Front St or entering its enormous front. Its interior is great however).

Personally, the reason I can’t find in my heart much respect for the modernist architectural movement, is the fact that modernist architects have evidently zero respect in their own hearts for earlier architectural styles. Right next to this article on the Spacing front page, is an article about how they’re going to glom a modernist addition to One Spadina Crescent:

http://spacing.ca/toronto/2013/06/11/u-of-t-reveals-new-design-for-one-spadina-crescent/

This glomming of modernist additions onto existing buildings, following a completely unrelated architectural philosophy, is not a rare and regrettable occurrence, but the general rule for such ‘extension’ projects. (The infamous ROM is a much-hyped FrankenBuilding now consisting of three architectural styles that have absolutely nothing to do with each other.)

Architecture, just like any real art, expresses the values in the architect’s soul (and indirectly in the souls of people who approve the project), on a level deeper and much more involuntary than any explicit statements they make about the value of heritage conservation &c &c.

And what these instances show me is a tradition that demands I respect its (yes, internally consistent principles), while utterly refusing to respect the internally consistent principles of earlier styles.

Old buildings with new, done well, as Spadina Cres looks like it will be, is how city’s preserve the old and still grow and absorb the new. This is how it should be. When new tries to pretend to be old, that’s when we get horrible faux historical bits. New should be new, and it’s ok if it’s next to the old. The Royal Conservatory of Music embodies this best in Toronto.

It’s an interesting question, though: Knox College may be good architecture, it may be bad architecture, but it was never “horrible faux historical” because it was built sincerely and preserved (or not) sincerely. The building was also itself new at one point, and designed according to a set of principles that certainly does not boil down to “try to pretend to be old”.

The point is not to “fake” an old building, but to build something that matches the architectural logic that was employed by the architects of Knox College, when Knox College was a new building. Or has the culture and capability required to build something like it been irreversibly lost?

If you were building on an empty lot, would you be capable of building in the style of Knox College, or would the result inevitably also be derided as ‘horrible faux-historical’? If so, what is the reason for this?

Is ‘heritage preservation’ really a case of us leaving old buildings up (not really caring about the *why* of them) to congratulate ourselves that we are still in continuity with our heritage when, in fact, we are not?