When nature calls in Toronto, it’s usually an obliging bar or cafe that answers. Outside of city parks and public buildings, public washrooms are practically non-existent. In fact, there are only three roadside lavatories servicing the 2.8 million people within our borders.

That today’s Toronto fails to provide for such a basic and frequent bodily function would come as a surprise to the aldermen of the 1900s for they were once busily engaged in establishing a fleet of public conveniences, many of them at major streetcar interchanges.

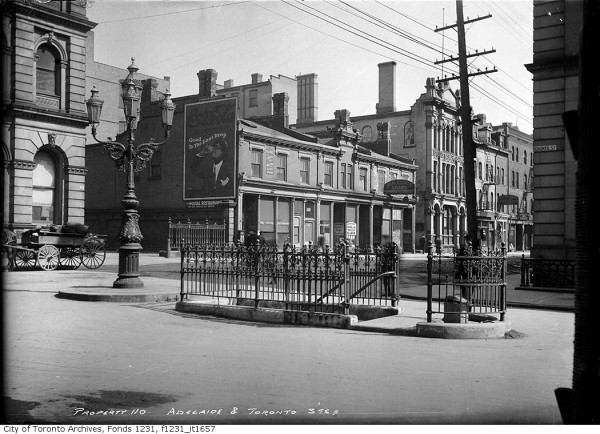

Toronto’s first public washroom, built in 1885, was located in the middle of Toronto Street, opposite the central post office building. It was supposed to be in a lane beside the Inland Revenue Office—later the Toronto Street Post Office and the headquarters of Conrad Black’s Argus Corp.—but nearby businesses balked at the idea, fearing nasty odours and unsanitary conditions.

The facility was accessed via a set of stairs, protected by an ornate iron fence, that descended into a small subterranean room. In the tiled, male-only washroom there was a set of four urinals, three wooden stalls, and an attendant who offered boot cleaning and fresh towels for a small fee of about 5 cents.

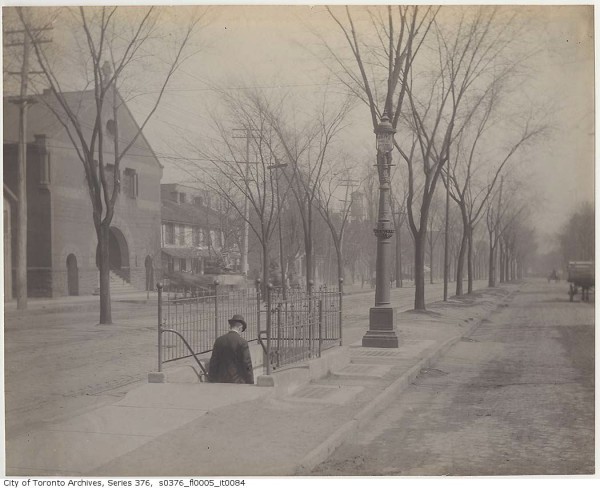

The Toronto Street lavatory was joined around 1905 by another, also in the middle of the street, at Queen and Spadina. A decorative light standard marked the entrance, which was a little west of the streetcar rails, just south of Queen. Needy male patrons were greeted by marble sinks and a welcome blast of warm air in winter.

The city never put together an official expansion plan, but the alderman of the age envisioned conveniences at streetcar interchanges. In 1911 and 1912, several civic leaders promised their constituents public toilets, variously at Dundas and Brock, Lansdowne and Dovercourt, Queen and Parliament, Bloor and Bathurst, and College and Spadina.

The College and Spadina toilet would become a touchy subject: The Broadway Methodist Tabernacle church, which once occupied the northeast corner of the intersection, was passionately opposed to a public convenience close to its property and fought for a full decade to have the concept shelved.

In the following years, underground toilets would be installed at Queen and Parliament, Queen and Broadview and above ground facilities at King, Queen and Roncesvalles, Dundas and Lansdowne, and other busy transit areas.

The Queen and Parliament location, also a source of contention with the neighbours, led to a lawsuit against the city by J. F. Brown and Co., the old occupants of the bright blue Marty Millionaire building. A judge ruled the toilet had “injured” the property and awarded the company $10,200 in damages. The city appealed the decision.

Similar issues surfaced in Riverdale. Many local residents wanted a washroom somewhere in the neighbourhood, but home owners close to each of the proposed locations were vocally opposed. Speaking to the Toronto Daily Star, an un-named person from the medical health department blamed widespread NIMBYism.

“Not long ago we were asked to place a lavatory in the northern centre of the city. Every site that we would pick, we would be assailed by petitions, indignant citizens, associations, and what not … it is certain where-ever we place the lavatory it will meet with a tremendous amount of protest, and because of that, we must proceed slowly.”

Then, in 1921, the decision that put the kibosh on the city’s tentative public toilet installation scheme: a new city bylaw required every new gas station (and there were soon to be many) to include a public washroom, essentially passing the burden of relieving the public to private companies.

Various schemes to expand public facilities were proposed and shelved through the 1920s before Toronto began the slow removal of its existing underground toilets. Alderman Fred Hamilton branded the Queen and Spadina location “the worst traffic hazard in the city” and “a menace” (this was before the streetcar right of way—the iron railing guarding the entrance steps was exposed to traffic) and, in 1939, it was filled in.

The idea of installing public toilets gradually grew less popular between the 1930s and 1960s. When the Yonge subway line opened in 1954, there were no conveniences for riders. “The city doesn’t provide such facilities in its police or fire stations and I don’t see why we should have to,” TTC chairman William McBrien said.

A small number of toilets were included on the Bloor-Danforth line, but still the city was reluctant to build, and more importantly staff, public washrooms. It was feared without an attendant the secluded rooms would become dens of iniquity.

In 1969, deputy police chief Harold Adamson told the Globe and Mail the city’s public toilets were “frequented by every-increasing numbers of homosexuals.” Deputy chief Bernard Simmonds said an average of six men a month were charged with gross indecency at TTC washrooms.

Toronto’s mayor William Dennison was of a similar mind. “[Public washrooms] have a bad effect on the neighbourhood,” he said. “They sometimes become hangouts for winies who are trying to sneak in and have a drink and dispose of the bottle.”

“Washrooms are not the kind of thing you would like to have next door to your business. They tend to create a blight … unless they are attached to a public building.”

By the late 1980s, the writing was on the wall for the washrooms that had hung on through the bad years. In a 1988 report, the city commissioner of public property recommended the last of the facilities—Danforth and Broadview, Queen and Broadview, Dundas and Keele and Cumberland and Bay—be closed to save money. Each one was estimated to cost between $2.47-$5.80 a flush.

The last “roadside” washroom at Danforth and Broadview—a 1921 brick, stucco, and wood structure with a pitched roof—closed in the late 1980s. Its tile interior and oak swinging doors were removed, and it now serves as a daycare centre.

For a moment in 2007, the dream of new public washrooms finally looked set to become reality when Toronto signed a deal with Astral media for 20 self-cleaning facilities. The contact was flushed in 2013 after only two installations so that the funds could be redirected to the ailing Bixi bike share network.

Need to go in Toronto? Today there is just one brick-and-mortar washroom that isn’t inside a civic centre or public park— it’s at Nathan Phillips Square, near the skate rental building, and it’s actually quite nice thanks to a recent renovation.

For the rest of us, there will always be Tim Hortons.

10 comments

There is also a big issue with the washrooms in city parks- They never seem to be open when we need them. And this is in the summer time, not the winter. The washroom in the park on Augusta near Kensington market has been locked up for months, I finally got annoyed enough to call 311 and was told there must be a maintenance issue. I questioned why it would be locked up for so long and got nowhere. I also often see washrooms in parks locked up by 8 pm. Isn’t that a little early ? Then there is the disgusting condition of most of the washrooms in city parks. Most of them need cleaning and painting to bring them up to decent standards. We should be encouraging people to get out and enjoy our parks, not discourage them.

I could be wrong, but isnt there a public washroom at Devid Pecaut Square. One of the hexagon shaped buildings?

…if they let you use it. Is there no corresponding bylaw in the city that says you can’t be denied the use of a washroom even if you aren’t a customer? While I can understand the perspective of a company which has that policy (I used to clean washrooms too, once in the restaurant biz — not fun) I seem to remember some years ago the city did actually forbid “customers only” rules. Unless I am mistaken of course.

In Europe, they have attendants on staff to clean and maintain washrooms. A coin is usually left as a tip.

I remember the Sunnyside public washroom. A dime (inflation today would make it a toonie) was required for the stalls, except for one which was free. No charge for the urinals. Toronto public washrooms used to have attendants, but even at minimum wage that must be why they got rid of them.

Isn’t the self-cleaning washroom still located at Queens Quay and Rees? These (this?) one(s) were accessible for a nominal fee of 25 or 50 cents similar to a payphone and are (probably as I’ve never used the one here) the same design used in places like Paris, Madrid and Brussels, which are free (since toilets on private property required a fee, even in train stations!). They would self-clean after each patron, which meant waiting for the “rinse cycle” to finish before using it. Brussels also has very basic public urinals available throughout the city similar to what was originally envisioned with the public toilets in Toronto.

6th Paragraph talks about a promised washroom at “Lansdowne and Dovercourt.” Or does the paragraph mean “On Dundas at Lansdowne, Brock, Dovercourt”

R.

Omg… Until I accidentally cam across this article I recently went back to Toronto for holidays after living in Australia for the past 12 years. I was 13 when I left so I didn’t remember a great deal just that its a wonderful city. Public washrooms are in abundance here in Perth. Our council even installed these 200k self cleaning high tech washrooms along the river fronts for joggers and picnic goers I guess this saves the local council on wages. Can’t be too good for the economy though I imagine. Most public washrooms here though do have the blue lights inside so that people can’t shoot up heroine inside them, the climate isn’t that cold in winder here at the most gets to 0 so we don’t have as many homeless shelters. However I couldn’t believe that on my trip to Toronto in the sub zero temperatures I couldn’t find a washroom anywhere!! whats the deal! my friend and I couldn’t believe we had to go into hotels and such just to use their bathrooms. It was the strangest thing ever, however I just put it down to the cold temperatures and risk of homeless people and crackheads calling a public washroom home.

It’s just so ironic – we needed more public washrooms in Toronto yet most wouldn’t want it installed in their neighborhood. A lot of us complain, even blame the government (although for some part they should make a thorough research of the best locations to put it), my point is – I mean both the people and the government should compromise to solve this issue.

@Al: Some time ago I was strolling along King Street West when all of a sudden I felt the pain of urine in my overflowing bladder. As I was walking past David Pecaut Square I saw the building to which you are referring. Up above the door I saw the blessed words, WASHROOM. Yet when I went to pull on the door handle, THE DOOR WAS LOCKED! My bladder screamed in pain.

Today I happened to follow a woman as we emerged from the Bathurst subway station mid-day. As soon as she reached the adjacent alley, she rushed into it about 5 metres and then crouched down, lowered her pants and began to relieve herself. So, yeah, public, visible washrooms seem a good thing, especially for those who can’t afford to buy a coffee at the corner coffee shop in order to use their washroom.