For an excruciating week in July, 1936, Toronto, the province, and much of Canada burned. An unprecedented and deadly continent-wide heatwave forced temperatures into the low- to mid-40s, killing hundreds, incinerating food crops, and forcing many more from their homes to sleep in parks, beaches, and cars.

The temperatures seen on July 7, 8, and 9 are still the hottest ever recorded in Toronto. The blast of searing weather also set records for Manitoba and Ontario that still stand today. The heat was so severe apples cooked on trees, crops died, houses burned, and bridges and roads buckled and warped.

The first signs of trouble came with the morning paper on July 7. A scorching heat that had menaced the Prairies and Northwestern U.S. was now sweeping east, forecasted said, with temperatures expected to linger in the low- to mid-30s in Ontario.

The situation in Ontario was already strained. Starved of rain for weeks, farmers in Western Ontario complained of dry wells and local creeks reduced to a languid trickle. The area from Hamilton to Niagara and Lake Erie was a “parched waste,” according to the Toronto Daily Star, with grain crops wilting and fruits and vegetables spoiling on the vine.

“The soil is bone dry and ground plants are sure goners unless we get some rain soon,” said Thomas Richardson, a fruit farmer in Normanhurst, Ontario. “The creeks are dried up, and many farmers here are hauling water from the nearest town.”

Temperatures on July 7 topped out at an uncomfortable 31 Celsius, but much worse was to come.

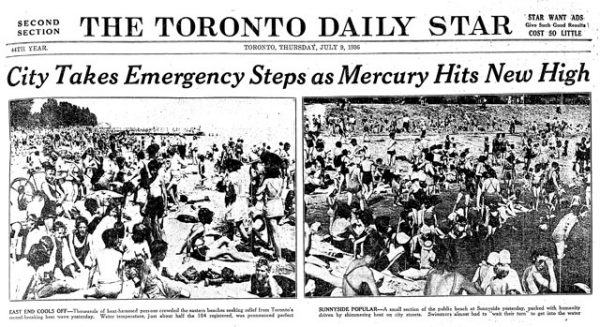

“The official temperature at 1:30 o’clock was 95 Fahrenheit [35 C] and is reported going higher,” the Star told its readers on July 8. In the sun, meteorologists recorded the temperature at 60 C, but that didn’t stop people crowding streetcars and ferries to the beach.

Sunnyside, Balmy Beach, and the Toronto Island all recorded record visitor numbers, while drivers lined Fleet Street hoping to fill the cabins of their vehicles with a whisper of lake breeze.

Over in Riverdale Park, the keepers gave the zoo animals extra water and tried to offer shade. However, there was no ice bath for the polar bears. “Ice isn’t put in the pool for the polar bears, because once wen this was tried in American zoo, the bears died,” a zoo official explained.

The city water supply was hit hard early on. Parched citizens chugged 104 million gallons from the tap and sprayed what was left onto their lawns that day—close to a record amount.

Though the Hospital for Sick Children reported no heat-related admissions, the effects of the weather began to manifest in people’s frayed tempers and angry outbursts. “The nervous strain and irritation caused by the heat would make noises seem more annoying than usual,” said University of Toronto Professor G. R. Anderson reliably informed the readers of the Star.

During the afternoon, the temperature hit 40 C—a new record.

Forecasters interviewed by the Globe and Star predicted the temperature would plateau, and they were right. On July 9 the official thermometers again read 40 C in the shade. In the sun, meteorologists recorded a mind-boggling 70 C.

“Weary to a point of exhaustion, men, women, children and animals sought refuge from scorching rooms and flocked in tens of thousands to the waterfront,” the Star reported. “They found little comfort there. The lake was like a mill pond. What slight breeze there was struck the face like a blast from a furnace.”

Without home air conditioning or any real way to cool down, people began to expire in increasing numbers. In Caledon, a 61-year-old man died while haying on a farm. Two drownings were reported—one in Hamilton, the other in Welland—as people headed to the water. James Gibbs, the Hamilton victim, leapt into the water though “he couldn’t swim a stroke,” according to his wife.

Fruits and berries cooked on plants across the city and people fried eggs on the searing sidewalk. At Sunnyside, a peanut and popcorn salesman named Tony tried to pop popcorn on the scorching asphalt without success.

The heat was so intense it caused the metal deck of the Cherry Street bridge to swell dangerously. Firefighters poured gallons of water on it to shrink it back down to size.

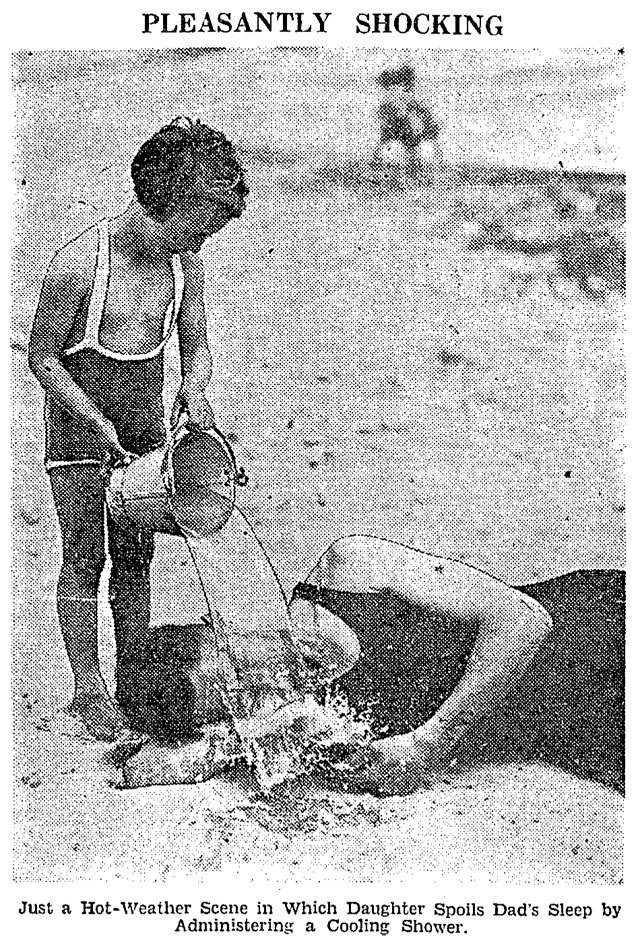

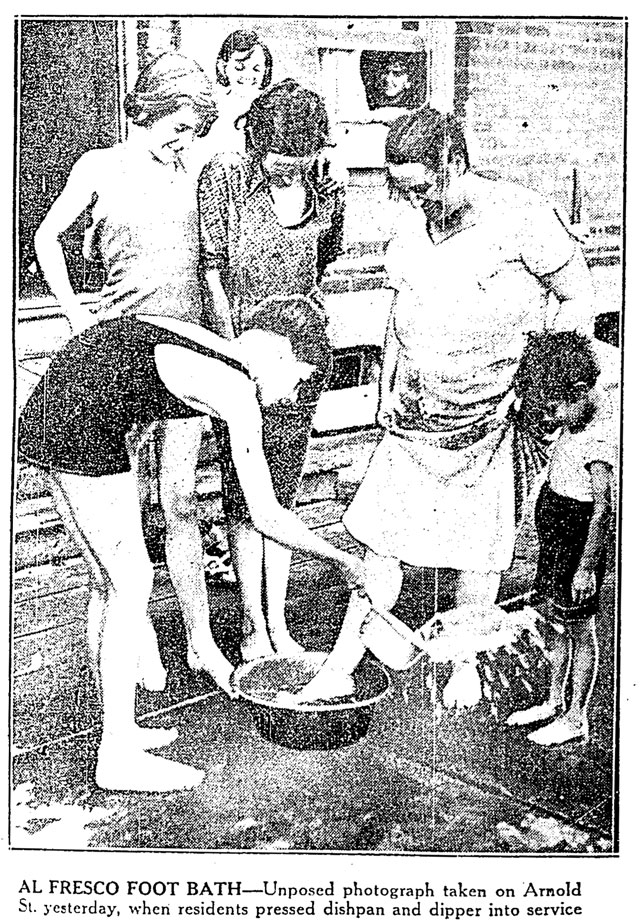

When stores ran out of electric fans, creative citizens reversed their vacuum cleaners, filled hot water bottles with ice cold water, or camped out in front of their refrigerators. Air conditioned movie theatres stayed open round the clock.

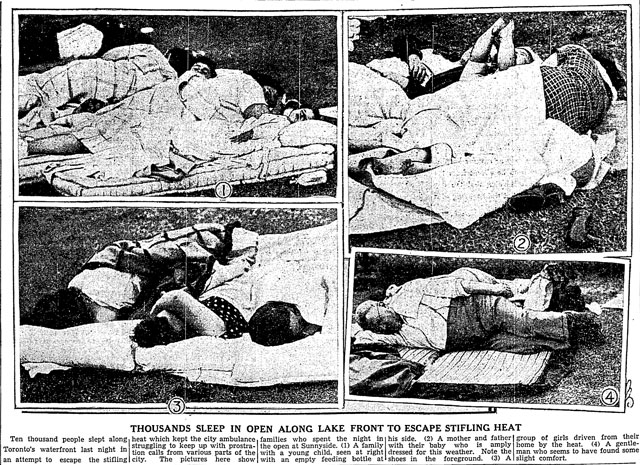

The most visible effect of the heat wave was the human exodus. Clutching mattresses and blankets, the Toronto waterfront from the Beach neighbourhood to Parkdale was jammed with people desperate to escape the temperature, even for a few moments.

“With no relief in sight, thousands of citizens went native, abandoning their houses,” the Star reported. “Donning bathing suits, pyjamas, shorts and the lightest of garments, they climbed into motor cars and made for Toronto’s thirteen miles of lake front to spend the night.”

In the early hours of the morning, beaches from Sunnyside to Kew were a sea of people—some sleeping, others enjoying the bizarre spectacle of the city uprooted and dumped on the lake shore.

“It was the younger crowd … who turned night into day,” wrote the Star. “They frolicked on the now cooled sands, swam in the refreshing water, built bonfires, turned on portable radios, strummed on guitars and whiled away the night with song and laughter.”

The third day of the heatwave, July 10, was when things started to unravel. With the temperature again 40.6 C, people began to die in significant numbers.

The Star and Globe newspapers started publishing lists of the deceased, which mostly consisted of old people and children. Some expired due to heart attacks, others due to drownings in rivers, canals, and lakes. Many fainted and didn’t wake up.

The Star recorded 22 deaths in Ontario at the time it went to press on the 10th. By next morning, that number had spiked to 80, and by the end of the week it had reached 550—225 of them in Toronto. The heat other associated misadventures were claiming so many victims morgue staff, grave diggers, and florists worked overtime to keep up with the demand.

Despite the extreme heat, the humidity was mercifully low—around 25 percent (a Humidex reading of 45 C.) Had it been higher the death toll would certainly have been worse.

By the time the heat finally dipped into the high 20s on July 15, more than 200 people in Toronto were dead. Across Canada, the final death toll was approximated to be 1,180.

A million dollars worth of crops across the province were ruined, the city’s water supply was about 30,000 gallons short of its normal level, and tarmac all over the city was rucked and curled.

“It is Hudson Bay air we have been getting last night and today,” said one weatherman on July 10, the first day of cooler weather.

“It surely makes a difference.”

3 comments

“It was the younger crowd… turned on portable radios, strummed on guitars and whiled away the night with song and laughter.”

Something is fishy here. 1936 predates the invention of a portable radio? https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Transistor_radio

What’s going on? Are the quotes referring to a different heat wave?

Hi JM. Portable radios were around in the 1930s. See this cheesy promotional photo: http://bit.ly/2ahVM35

In those days, lots of people had radios that weren’t necessarily designed to be portable but were battery-powered so could be pressed into service on the beach. The heat wave came just before my 1st birthday, and I survived in the basement of our London, Ont., house with my mother repeatedly standing me in a galvanized-metal laundry tub and pouring cold water over me.