As archeologists begin to reveal two centuries of commerce on the North Market site, Toronto’s other major active dig site – the Centre Avenue parking lot that’s set to become a major new courthouse – has been fitted out with a hoarding mural display that evokes the stories of the city’s original arrival city, The Ward.

At a formal unveiling last week, the hoarding project – commissioned by Infrastructure Ontario and developed by the Toronto Ward Museum, The STEPS Initiative and visual artists PA System (Patrick Thomson and Alexa Hatanaka) – offers an innovative and stylized depiction of artifacts found on the site, as well as archival photos, and narratives and images of individuals linked to the neighbourhood’s various eras and demographic groups.

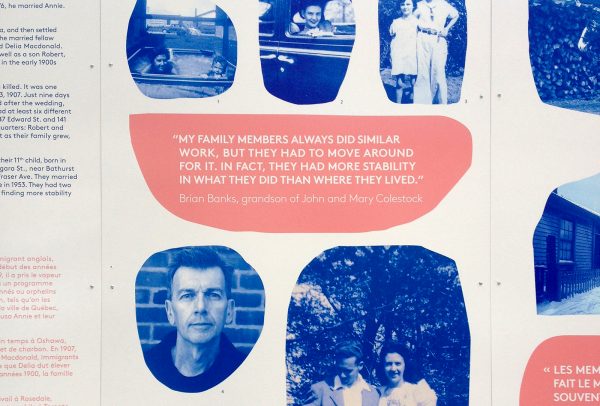

(Toronto writer/editor Brian Banks, and the stories of his ancestors who lived in The Ward.)

While the murals add a visually striking note to a long-neglected block, the execution is not without flaws: the text on some of the panels contains typos. As well, several of the guests who attended the unveiling, including those involved in the project, commented on the fact that some of the archival images of The Ward scenes installed along the Armory Street panels are printed backwards. At least one described the effect as disrespectful.

That move, however, was intentional. “The mirroring effect was used to create a continuous feeling of walking through a historical streetscape,” according to a statement by PATCH, the project facilitators who worked with The Toronto Ward Museum and designer Kellen Hatanaka on the exhibit. “The mirroring also allows alignment of the images in such a way that its effect is amplified and immersive, while allowing the viewer the experience of entering the exhibit from either side of the installation.”

In an interview following the unveiling, John McKendrick, IO’s executive vice-president for project delivery, and Reza Asadikia, director of major projects, outlined new details about the courthouse venture, which will become a major landmark structure estimated to cost between $500 million and $1 billion. It will be built under IO’s alternative financing and procurement model.

(Ward 27 councillor Kristyn Wong-Tam and IO executive vice-president John McKendrick)

Proponents: Two major design/construction consortia responded to the request for proposals released in the spring.

One is The Plenary Group, an international Triple-P firm that has built numerous large IO projects, including the Humber River Hospital and a new courthouse in Thunder Bay. It includes construction conglomerate PCL, the U.S. design giant Perkins Eastman, and architect Carl Blanchaer, of WZMH, which designed a new courthouse in Durham.

The second team includes London, Ont-.based design/build powerhouse Ellis Don Infrastructure, David Clusiau, who heads NORR’s Toronto architecture group, and the Paris-based international firm of Renzo Piano, which has designed museums, airports and major buildings around the world.

McKendrick says both teams are currently developing their proposals and he expects bids to be tendered in the spring, with a winner selected soon after. Construction is expected to begin late next fall and will last for about four years.

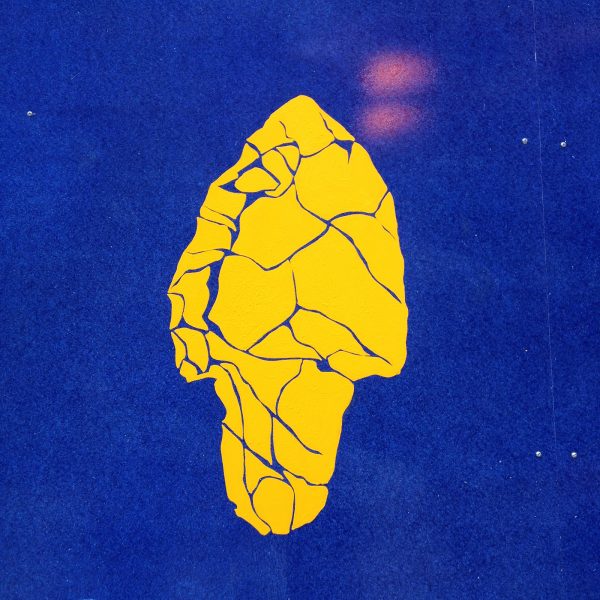

(Stylized image of an arrowhead found on the site; PA System.)

Design Principles: A modern criminal courthouse in Ontario must have state-of-the-art security, controlled entrances, no public parking below grade, and exterior features capable of blocking vehicular attacks. But McKendrick says both teams have been told to ensure that the project doesn’t look and feel like lock box.

That means emphasizing transparency and lighting at grade, designing a spacious and inviting lobby area, and developing exterior landscaping that provides the necessary security without replicating the heavy bollard-and-concrete-planter protection at the U.S. consulate on University Ave. The teams, McKendrick adds, should be proposing urban design elements that link the building to Dundas Street and Nathan Phillips Square. “We want this to be a beautiful courthouse,” he says.

Neutrality: The design of courthouses, according to Government of Ontario guidelines, “must be respectful of the independence of the courts,” McKendrick says. But he stresses that this goal need not exclude design choices that reflect local interests, such as heritage interpretation and commemoration. He points to projects such as IO courthouses in Thunder Bay, a Plenary Group project which was designed to incorporate indigenous themes, and Port Hope, an Ellis Don/NORR restoration of a heritage structure that includes historical artifacts in the lobby area.

(Former Chinatown resident Mavis Garland with an image of her father’s mahjong set.)

Ward Heritage Commemoration/Interpretation. McKendrick says IO and its bidders are consulting with a heritage interpretation working group in order to develop strategies for acknowledging the site’s rich history. During last year’s dig, London, Ont.-based archeologist Holly Martelle and her team found hundreds of thousands of artifacts, as well as the foundations of an historic black church, a Russian synagogue, 19th century row-houses, factories and dozens of privy pits that contained a wide range of household objects dating back over a century. The dig also yielded the largest trove of 19th century shoes ever discovered in Canada.

Historian archeologist Karolyn Smardz Frost described the excavation as Toronto’s “most important black history site” because of the presence of the British Methodist Episcopal Church, which was established on Chestnut Street in the 1840s by some formerly enslaved African-Americans and later served as an important community and religious hub for Toronto’s black community for almost a century. After the congregation relocated, the building was acquired by the Toronto Chinese United Church, which operated there until the late 1980s, when it was demolished.

As part of the city’s development approvals process, IO was required to submit a heritage interpretation strategy, which includes elements such as interior and exterior signage, displays, floor markings and other means of drawing out the stories of the various immigrant groups – African American, Irish, Italian, Jewish and Chinese — that passed through the Ward.

The two design/build teams will offer specific proposals as part of their bids and have been encouraged to “go above and beyond” the city-approved interpretation strategy, says McKendrick. “It will be important that the history of The Ward is reflected inside the courthouse and outside, on the plaza.”

Full disclosure: I co-edited The Ward: The Life and Loss of Toronto’s First Immigrant Neighbourhood (Coach House, 2015)