No Toronto neighbourhood paid for the Gardiner Expressway quite like Parkdale.

Before construction of the lakefront highway in 1958, the land south of Springhurst Avenue and the rail tracks was just like the rest of Parkdale: residential, consisting of mostly detached homes on spacious lots.

At the time, Dunn and Jameson Avenues passed over the rail tracks south to the waterfront and a tangle of smaller streets such as Laburnam and Starr Avenues, Empress Crescent, and Hawthorne Terrace intersected them.

South Parkdale was distinct enough to have its own railway station near the present-day foot of Close Avenue.

The first major road to penetrate the neighbourhood was Lake Shore Boulevard, which snaked south of Exhibition Place along the waterfront toward the Humber River in the 1920s.

In South Parkdale, Lake Shore Boulevard was created by merging and widening a number of residential streets, including Laburnam Avenue and parts of Starr Avenue.

There are subtle clues to the existence of these old streets. Lake Shore Boulevard subtly winds in the area north of Marilyn Bell Park, mirroring the former the routes of these lost streets.

The clearest example of this is where Lake Shore Boulevard turns sharply north to avoid the Toronto Sailing and Canoe Club near Dowling Avenue.

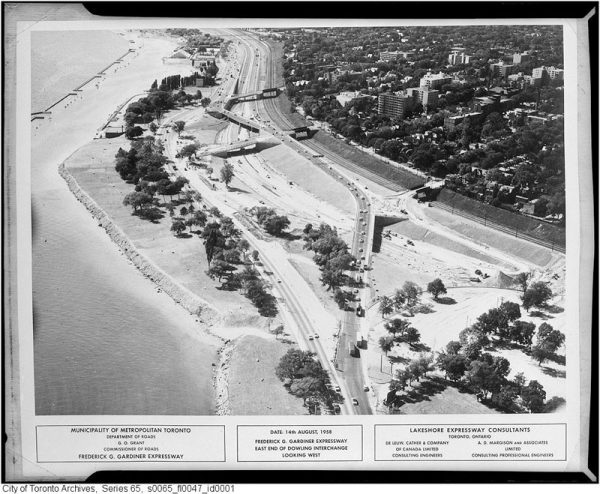

For the next few decades, South Parkdale remained relatively stable. Lake Shore Boulevard was five lanes wide and often busy with traffic, but houses and driveways still lined the route. The eventual destruction of the neighbourhood came in 1956, when construction began on the Lakeshore Expressway.

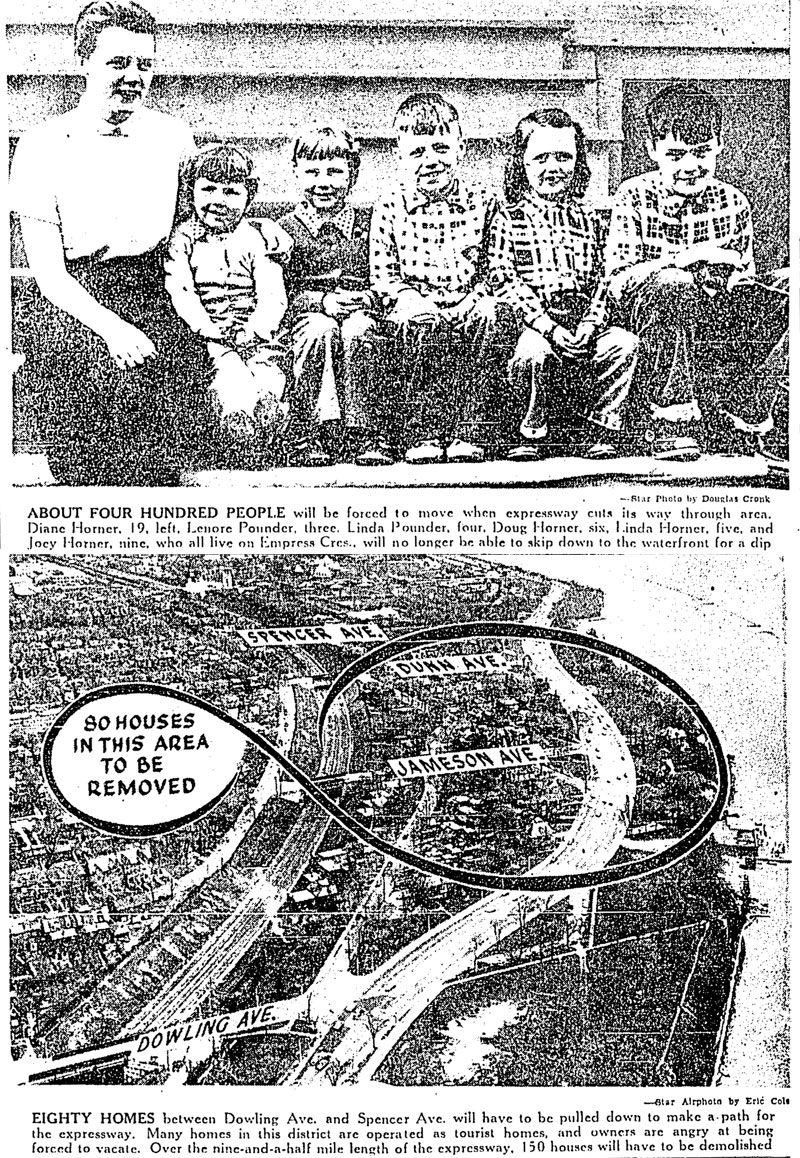

About 150 homes and 400 people were forced to make way for the expressway when the route was announced in 1954. For Dorothy Wood, who lived on the south end of Jameson Avenue, it was just history repeating itself. When she was young her parents’ home was expropriated for Lake Shore Boulevard.

“When they pulled down our house for Lake Shore Boulevard, we moved into this house,” she told the Toronto Star. “I like the location. It is cool in the summer—I don’t know where I could find another place like it in Toronto.”

Mrs. K. B. McKellar of Starr Avenue expressed similar feelings. “I love it here. I don’t want to move,” she said. “We have a very nice garden and a very pleasant view of the lakefront.”

Mr. C. L. Ellis, who operated a tourist property in the neighbourhood, took the news with a shrug. “If they hand us a big enough cheque for this property, we won’t kick too much,” he said. “But we’ve been here four years, we’ve put a lot of money into the place and we like the location.”

In 1956, photographer James Salmon pictured the condemned streets shortly before construction on the expressway began. The roads and sidewalks were empty and the yards overgrown and strewn with leaves. Within weeks, it was all gone.

To make a path for the Gardiner through South Parkdale, almost all the streets south of King and west of Dufferin were demolished. The houses on Starr Avenue, Laburnam Avenue, Empress Crescent, and others were all torn down and the trees, sewers, and fire hydrants removed.

Workers dug a trench for the new highway to the south of the rail corridor, creating a stark landscape that captured the imagination of a young novelist, playwright, and poet Milton Terrence Kelly.

“Parkdale was a construction site. All the Victorian homes, including the one next door to where my best friend lived, were being torn down for apartment houses,” he recalled.

“The great trench of the Gardiner went through, cutting us off from the Lake. While it was being built, we played there, pretending we were wolves; the ramp led up and fell off, as eerie and windswept as a desert.”

The area didn’t stay quiet for long. When the road opened in 1962, cars and trucks filled the highway and its access roads. Lake Shore Boulevard bloated to its current proportions, essentially acting as a second parallel expressway.

The former location of South Parkdale is now so dense with highways, feeder roads, overpasses, and traffic noise it’s difficult to imagine a time when it was anything like the rest of Parkdale.

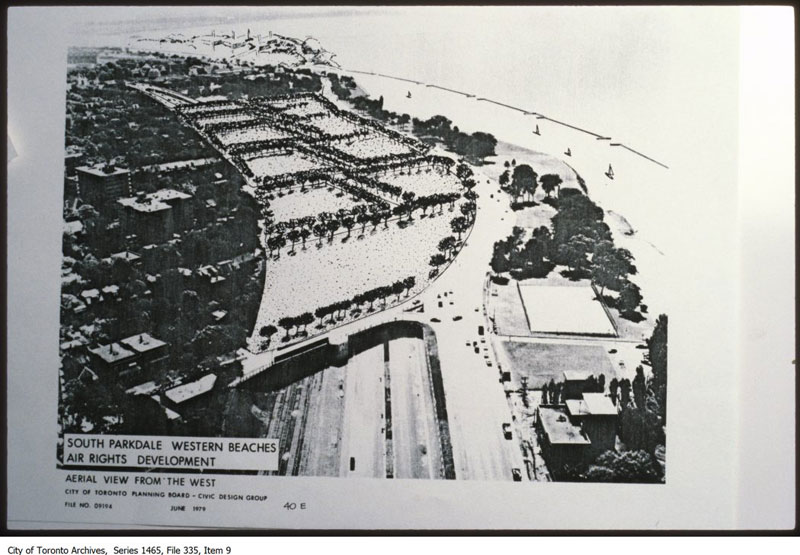

Toronto mayor John Sewell and Metropolitan Toronto chairman Paul Godfrey announced a plan with the potential to bring back South Parkdale in 1979.

At their direction, city planners studied the feasibility of covering over the Gardiner and rail corridor between Dowling Avenue and Exhibition Place, creating about 40 acres of new land for residential development.

Drawings from the resulting report showed mid-rise buildings on a restored South Parkdale street grid north of Lake Shore Boulevard.

“To encase the rails and road would indeed be grandiose,” wrote Globe and Mail columnist Dick Beddoes. “We’d have a mile-long covered corridor, which presumably, we’d call the Godfrey-Sewell Secret Passage. Or Tunnel Job.”

He clearly didn’t think much of the idea.

The tunnel plan was projected to cost somewhere in the region of $25-million, according to Parkdale councillor Barbara Adams, but nothing much came of it save for some paperwork.

South Parkdale will have to wait for its return.

2 comments

Why don’t we widen the 400 around Mayor MacKenzie Drive, bulldozing Canada’s Wonderland in the process. Just like they did with Sunnyside Amusement Park in the 1950’s, to make room for the Gardiner Expressway.

Hwy 401’s widenings over the years have also swallowed homes. If you compare early 1950s aerial photos with Google maps, you’ll see whole blocks of homes have been demolished.

http://www1.toronto.ca/wps/portal/contentonly?vgnextoid=fb38757ae6b31410VgnVCM10000071d60f89RCRD&vgnextchannel=7cb4ba2ae8b1e310VgnVCM10000071d60f89RCRD