The three towers of the City Park co-op apartments on Wood Street behind Maple Leaf Gardens don’t really stand out among the numerous high rises of the Church-Wellesley Village.

But the anonymity of the trio of 14-storey towers belies an important piece of Toronto history because this was the first Modern, multi-building apartment complex in the city and, at the time of its construction in 1954, the biggest residential project in the country.

City Park was conceived in 1952, when Toronto city council formally identified the land enclosed by Wellesley Street, Jarvis Street, Wood Street, and the future subway line as a target for redevelopment.

The Yonge line, under construction along the western flank of the area, was expected to drive prosperity and force out slum conditions that had developed among the mostly Victorian housing stock. Many of the homes close to Carlton Street were in particularly bad shape due to years of neglect by the landlord, the T. Eaton Co. department store chain.

Eaton’s wound up owning the future site of City Park in the 1910s following a dizzying and unprecedented three-day land acquisition spree. In just 72 hours, the company bought up 75 percent of the land in the two blocks north of Carlton between Yonge and Church Streets.

The haste was necessary to avoid news leaking that Eaton’s was planning a new midtown store in the area.

As it happened, Eaton’s College Street was built on the southwest corner of College and Yonge in 1928, but the company continued to own the land it had assembled, selling it in pieces for Maple Leaf Gardens and the Toronto Hydro headquarters in 1931.

By the 1950s, the department store was leasing the homes on the land it owned between Wood and Alexander Streets, allowing many to fall into disrepair and subletting to get out of control.

Toronto alderman William Dennison called it “a civic disgrace, an eyesore of the worst kind.”

To remedy the situation in the Carlton Street area, the city offered to expropriate parcels of land and lease them to developers willing to put up high-rise buildings in a style “similar to … the east side of New York”.

At the same time, the city was planning the second phase of the Regent Park housing project south of Dundas and had also identified the houses east of Trinity Bellwood Park between Queen and Dundas as substandard and in need of redevelopment.

A group of citizens calling themselves the Bloor-Cartlton Ratepayers’ Association formed to oppose some aspects of the College Street-area redevelopment plan, particularly the city’s unusual offer to expropriate the land.

“Why isn’t some other district of Toronto named for redevelopment,” wondered John Downes of Maitland Street to the Globe and Mail. “If people want to redevelop the town why don’t they do it somewhere else?”

The ratepayers’ group agreed, however, that the future site of the City Park complex was suitable for renewal of some kind.

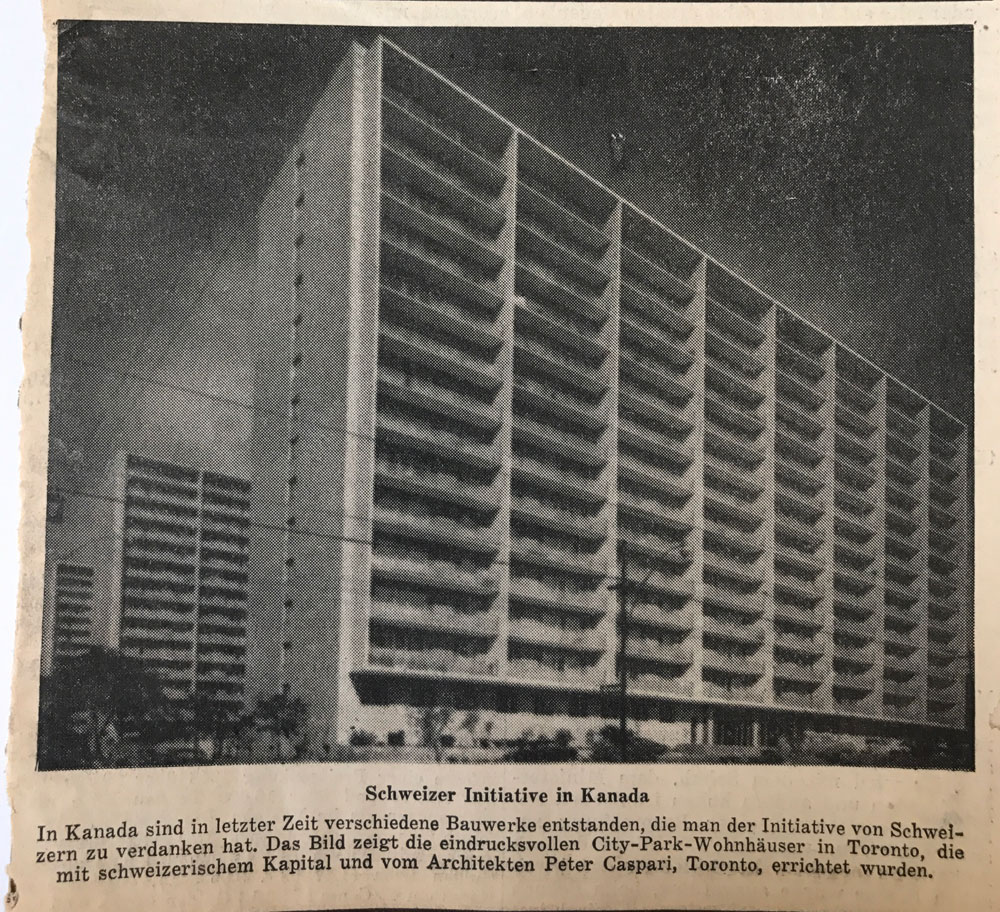

The plan for City Park revealed to the public in 1952 was designed by Peter Caspari, a Jewish, German-born architect who fled his home country during the build-up to the Second World War, eventually settling in London, England where he designed several Streamline Moderne apartment buildings.

Caspari arrived in Toronto in the early 1950s and he designed the Vincent Court and Buckingham Court apartment buildings on Eglinton Avenue and several others during his first few years in the country.

When it was announced, City Park was Caspari’s largest commission to date. In fact, it was also the largest private development proposal in Canada, with an anticipated 1,000 middle-income units spread between four, 15-storey towers.

The $8 million project was financed by Swiss building company, Hubert Buildings Ltd. Instead of asking the city to expropriate (as had first been suggested), the developers bought the land from International Realty Co., an Eaton’s subsidiary, for $500,000 in February, 1954.

By the start of construction, the original City Park plans had been scaled back slightly. Instead of four towers, the complex would consist of three, 14-storey towers.

“[The switch to three buildings] allowed better light use and larger landscaped areas between the buildings than would otherwise have been possible,” architect Caspari wrote in the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada Journal in 1957.

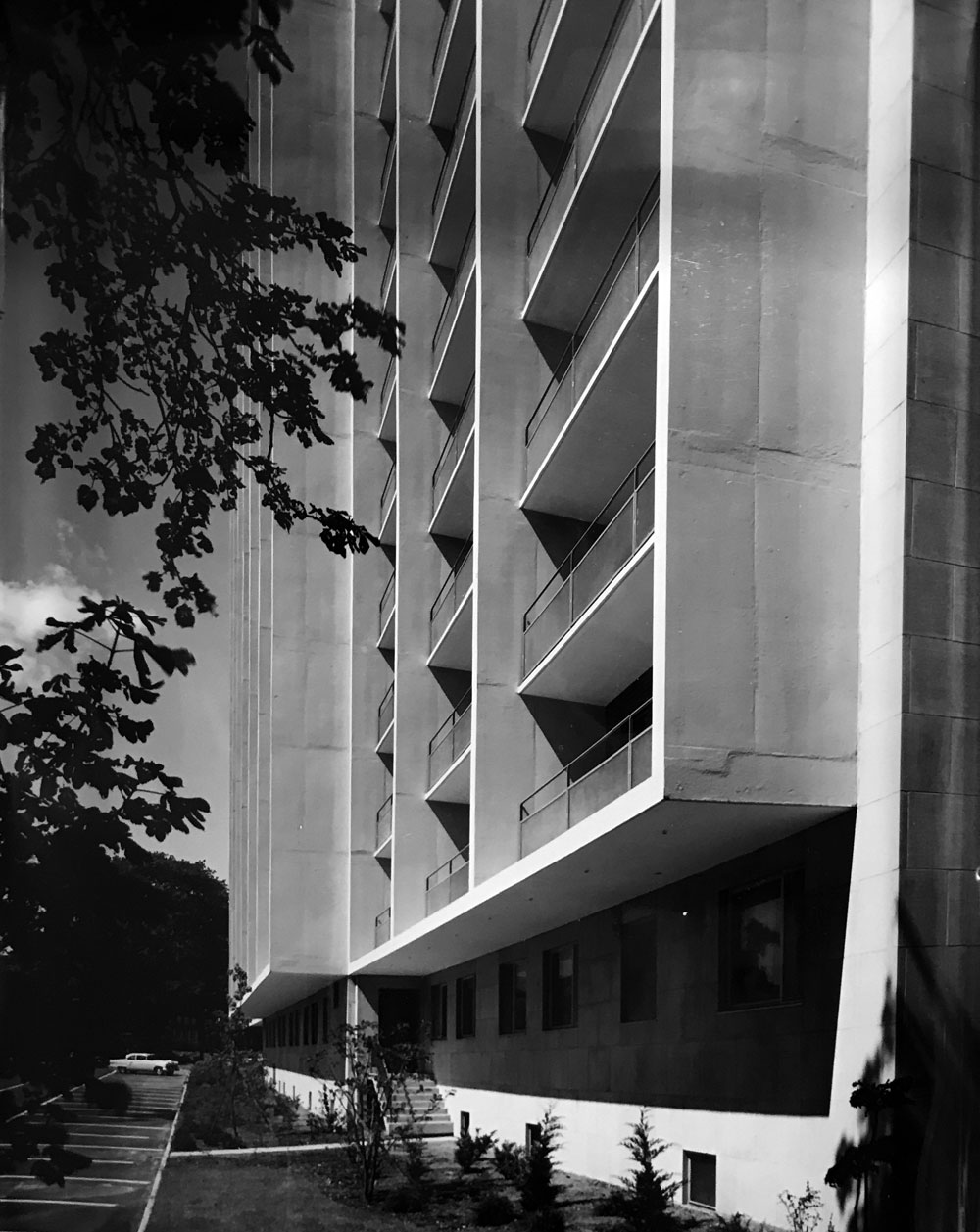

Caspari also simplified his towers, creating three geometric blocks made almost entirely of reinforced concrete. Even the walls between the indviidual units were made of poured concrete “to eliminate all noise transmission between apartments and public corridors,” Caspari wrote.

Caspari was extremely concerned about noise transmission. In addition to the thick concrete walls between units, “special acoustic plaster” was sprayed in the public passages and the units were arranged so the bedrooms were separated from the entryways by at least one internal door.

Double-glazed windows made in Switzerland reduced outside noise and noisy boiler equipment was separated from living areas by the communal laundry rooms.

The city gave Caspari special permission to include one parking space for every three units, rather than the one-for-one ratio stipulated in the planning bylaw. In total, there would 774 suites with 578 parking spaces underground and on the surface between the towers.

Construction began with the demolition of the homes on the Wood-Church-Alexander-Yonge block in 1954 and the project was completed approximately a year and a half later in 1956.

The crisp International Style apartment towers were “as modern as tomorrow,” according to the complex’s promotional pamphlet. Each unit opened into a “continental style” hallway off which the various rooms and closets were located.

The living areas came with hardwood parquet floors, built-in TV outlets, and French windows that opened onto a full-length balcony. The kitchens came fitted with General Electric appliances in a range of pastel colours—turquoise green, canary yellow, or satin white—and a milk box connected directly to the hallway for easy deliveries.

There were sun gardens on the roof of each tower and the lobbies were decorated with marble floors and polished terrazzo walls.

Bachelor apartments started at $90 ($830 in 2017) a month, one-bedrooms were $155 ($1430, 2017), and the most expensive units—two-bedrooms on the top floor—were priced at $195 ($1,800, 2017).

City Park was noticed around the world when it was completed. The Swiss financial backing of the towers generated front-page newspaper coverage Der Bund, a national German-language newspaper based in Bern.

The UK Sunday Times also noticed the development. In a full-page story on the benefits of emigrating to Canada written by former Chancellor of the Exchequer Peter Thorneycroft, the crisp white Church Street towers appeared beside a photograph of the Rocky Mountains as symbols of this country.

The towers were “an outstanding example of Modern Canadian architecture,” the piece noted.

In an attempt to build on the success of City Park, Toronto began seeking bidders willing to develop the next block north, between Maitland and Alexander Streets. As a sweetener, the city pledged to this time expropriate the land and lease it to a developer of its choosing.

The eventual winner, Ridout Real Estate, proposed 1,500 residential units spread across eight 17-storey towers.

As part of the deal hammered out during an all-night city council session, the city would buy the land at a cost of $5 million and lease it to Ridout, allowing it to build its $17-million complex.

The financial arrangement proved controversial, so Ridout agreed to withdraw its plans and resubmit with other developers in 1956, but the project soon became mired in problems. Firstly, only a handful of developers submitted acceptable proposals (one contained a heliport), then the city was denied federal money that would have covered the cost of expropriation.

In January 1957, Ridout went bankrupt, further jeopardizing the redevelopment. In February, the Globe and Mail described the city’s attempt at a public-private development partnership as “an object lesson in how not to handle redevelopment.”

Peter Caspari and the developers of City Park made an offer that would have mostly covered the cost of expropriation in exchange for the right to put up four buildings on the site, but were unsuccessful. The city repealed the development bylaw in June 1957, ending the experiment.

It would be almost 10 years before the block was privately developed as the Village Green complex.

Caspari went on to design the CIBC tower at 2 Bloor Street West, which was completed in 1974 and was his last major work in Toronto before retirement.

He died in 1999 having introduced Toronto to the post-war high-rise.

5 comments

Nice Chris! Did you see this?

https://beta.theglobeandmail.com/life/home-and-garden/architecture/peter-caspari—a-bull-who-helped-shape-toronto/article21949216/?ref=http://www.theglobeandmail.com&

I feel so blessed to live here in City Park.

Great historically coverage of a unique housing project in Toronto, Canada. I first lived on Wood St. when I arrived in T.O. 1984. I always admired City Park as a housing community.

there’s also an important queer history connection to City Park Co-op .. ex City councillor Kyle Rae explores this in a short doc which is part of the Queerstory locative history app: http://www.queerstory.ca/project/city-park-co-op/

I admire City Park. I always pay attention to all interesting things in Toronto. Especially I like following this https://www1.toronto.ca to be aware of improvement of the city. But except this I am interested of safety modern and old-fashioned buildings. I like to be safe because in some district can be burglars. I was a victim once and after that time I was searching for safest places and district of this city and finally find one and immediately after moving in changed security system of my apartment and building https://matrixlocksmith.ca/