By Ellen Scheinberg and Jim Burant

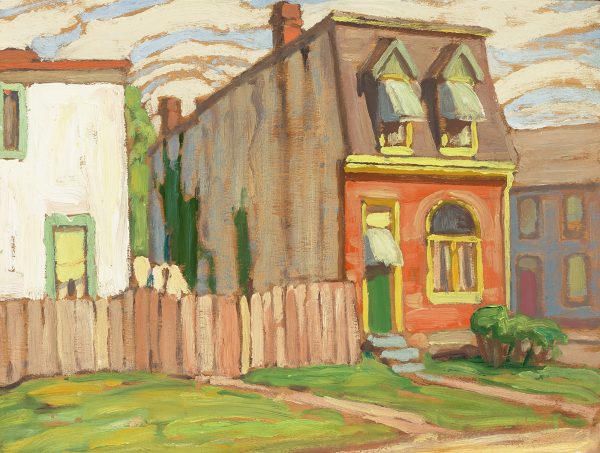

In May 2016, a Lawren Harris painting entitled Toronto House was offered at auction, and purchased by a local art aficionado for $115,000. Produced around 1920, this charming, diminutive oil on panel, 10.5 x 14 inches in size, features vibrant colours. Details regarding the owner of the home depicted in this work and its location in Toronto were unknown. Its provenance, however, was irrefutable; the painting had been part of the estate of Harris’s second wife, Bess Harris, and after her passing, owned by his youngest son, Harry K. Harris, until last year’s sale.

Compared to Harris’ dramatic northern landscapes, his Toronto House paintings are less known and appreciated. The purchaser was however very interested to learn more about the work, particularly where the original house might have been located, Harris’s connection, whether it still existed, and if there were archival photographs. We were hired to carry out the research. Due to the absence of a street name, the purchaser understood there was no guarantee of success. Moreover, since so many of Toronto’s workers’ cottages have been demolished, the initial assumption going into this project was that the house in this painting had fallen victim to the wrecking ball years ago.

Surprisingly, our hypothesis proved to be wrong.

Canada’s Urban Artist

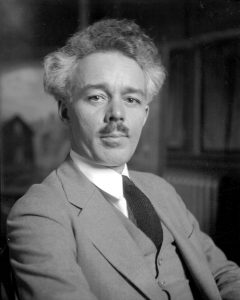

Despite his reputation and fame for his northern landscapes, Lawren Harris (1885-1970) is perhaps the best-known artist of urban life in Canada. Early in his career, Harris developed a close friendship with J. E. H. MacDonald, a fellow artist and co-founder of the Group of Seven. Together, they roamed the streets of downtown Toronto, recording in pencil many sketches of hitherto neglected subjects — corner stores, backyards, and workers’ houses — particularly in and around The Ward. Indeed, during the first 20 years of his career, the life of the city was a dominant subject in Harris’s thoughts about art and representation.

These sketches formed the basis of a series of numbered paintings, some of which were exhibited in 1911 at the annual exhibition of the Ontario Society of Artists. Many bore titles that described their subject in evocative and yet geographically vague terms: “Winter Twilight” (1911, Art Gallery of Hamilton), “Old Houses,” “Toronto Street,” or “Corner Store.” There are some rare exceptions, such as “Houses, Gerrard Street, Toronto” (1912, McMichael Canadian Collection). From March 1919 to August 1921, Harris exhibited 37 paintings of urban subjects. Increasingly drawn towards the Canadian landscape, and to notions of abstraction, Harris virtually abandoned the subject of urban life by 1926, probably discouraged by the lack of sales.

The Toronto House painting purchased by the client was created around 1920 and somewhat distinct from Harris’s other depictions of Toronto houses. The subject was a detached, two-storey home, with a sizeable front yard. In order to identify the neighbourhood, we consulted Tatum Taylor and Scott Weir of ERA Architects. Both identified the residence as a Second Empire Style home from the late 19th century, with a mansard roof and dormered windows. The charming home in Harris’s painting, they noted, was intended to serve as a 19th century worker’s cottage. Weir suggested several locations in the city where they are commonly found.

The Toronto House painting purchased by the client was created around 1920 and somewhat distinct from Harris’s other depictions of Toronto houses. The subject was a detached, two-storey home, with a sizeable front yard. In order to identify the neighbourhood, we consulted Tatum Taylor and Scott Weir of ERA Architects. Both identified the residence as a Second Empire Style home from the late 19th century, with a mansard roof and dormered windows. The charming home in Harris’s painting, they noted, was intended to serve as a 19th century worker’s cottage. Weir suggested several locations in the city where they are commonly found.

The specific location of this house, however, remained a mystery. Two archivists from the City of Toronto Archives, Lawrence Lee and Patrick Cummins, joined the search. Cummins has photographed the city’s built heritage for many years, and is the co-author of Full Frontal T.O. (Coach House Books, 2012) with Spacing writer and editor Shawn Micallef (Cummins is also the photographer of the image on the summer 2017 issue of Spacing). After examining the painting, Cummins immediately recognized the site as Yorkville. Once the neighbourhood was identified, we relied on both archival photographs and Google Maps to search for the specific building. While virtually strolling down the streets of Yorkville in her office using Google Maps, Ellen spotted a structure that resembled the Harris home, at the corner of McMurrich Street and Roden Place. When comparing the photo of the painting to the on-line image, it became apparent the home was still standing.

Once we had the location, it became much easier to trace the building’s history. From information in the City archives, we learned the house had been constructed by William Adams, who secured a building permit in 1887 to construct eight row houses as well as this single home for $800 each on McMurrich. He had purchased the land from the estate of the late John Bugg, an alderman from 1852 to 1872. The original address of the home was 65 McMurrich. This simple but stylish home is just 14 feet wide, and a total 950 square feet. It features a stained glass fan above the ground floor window along with dormered windows on the second floor.

Adams faced the first level with bricks, likely acquired from the local brickworks, now the Evergreen Brickworks site. Above the bricks was a facing of shingles, while the back and sides of the home were fabricated with rough cast plaster. The basement walls were constructed with remnant bricks from the brickyard.

The first tenant was carpenter and builder, H.F. McLean, who occupied the home in 1889 with his wife and three children. The early residents of McMurrich were working people — carpenters, brick workers, and builders — of Anglo-Celtic descent. Some of the nearby institutions and businesses included the Magdalen Asylum, a home for aged women, an organ factory, and two major breweries.

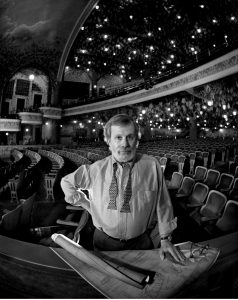

City directories reveal that several families have occupied this home since its construction. The most prominent was architect Mandel Sprachman, who designed and restored some of the finest theatres and cinemas in the country during his illustrious career. These included the Elgin and Winter Garden theatres. Sprachman ran his office from this house after he purchased the property around 1971. He also legally altered the address to 30 Roden Place, and subsequently ran a competition to change the name of the street, viewing the existing name as too “rat like” (He had a change of heart after receiving a plea from the Roden family to retain the original name). Sprachman subsequently moved the entrance to the east-facing side of the house and ensured that it was added to the City of Toronto’s Heritage inventory in 1973.

The Sprachman family owned the Roden Place house depicted in Harris’s painting for 45 years, until its sale in December, 2016. According to Mandel’s son, artist Robert Sprachman, the structure is in very poor condition. Consequently, the new owner will either need to initiate expensive renovations and structural enhancements before occupying the home or raze the building and replace it with a larger, more modern home. Currently, there are only 25 heritage properties left in this neighbourhood. Most of the oldest have been demolished and replaced by condos, like the one built adjacent to this house.

Finding the Toronto House

Why did Lawren Harris decide to paint this house? It is possible he passed the area on his daily trek from his home on Queen’s Park Circle to his studio, situated nearby on Severn Street. He may also have sketched it during one of his artistic outings with MacDonald. Not only were we fortunate to find this charming home astonishingly intact, but it was serendipitous to discover that it had been owned by the Sprachmans, whose family is closely connected to both Patrick Cummins and one of the authors. While the market value of Harris’s landscapes continue to reach new heights at auction — one sold for $ 11.2 million in 2016 — many of the artist’s Toronto house paintings remain less well known and appreciated. This is particularly true of the ones devoid of location details or of titles that could identify them. Once one has established the location, history and pedigree of a “Toronto House” painting, it automatically imbues the work with far greater appeal, value, and in a case like this one, cachet.

Our search also reinforced the distressing fact that this particular house is most likely an anomaly: many of the homes painted by Harris have already disappeared. Toronto, in its quest to pursue continued growth and development, has forgotten its rich built heritage, as new office buildings, condos, transportation routes, malls and arenas take the place of industrial buildings and housing. Despite the valiant efforts of the City’s Preservation Services staff, Heritage Toronto, local activists, and a handful of city councillors, significant architecturally- and historically-significant buildings of all types have been demolished, as a recent incident involving the Bank of Montreal building on Yonge Street north of Eglinton has demonstrated.

If Mandel Sprachman hadn’t had the foresight and commitment to heritage preservation to place this building on the heritage inventory, 30 Roden Place would likely have met the same fate as many other 19th century cottages in the city. Ironically, in an Globe and Mail interview with Sprachman in 1982, he voiced considerable optimism when it came to heritage preservation:

If Mandel Sprachman hadn’t had the foresight and commitment to heritage preservation to place this building on the heritage inventory, 30 Roden Place would likely have met the same fate as many other 19th century cottages in the city. Ironically, in an Globe and Mail interview with Sprachman in 1982, he voiced considerable optimism when it came to heritage preservation:

“Ten years ago, we thought new is better. Everything was developer-oriented. Tear down the old City Hall for a department store, but yes save the bell tower! Today our thinking has changed.”

Evidently, such trends are cyclical, and the city’s historic homes and treasures, like old City Hall, are in peril once again from avaricious developers. Mandel Sprachman’s records reveal he was likely unaware of the connection between his Second Empire office and Lawren Harris. He therefore appreciated the residence for its aesthetic, historic, and architectural qualities.

Hopefully, the pervasive passion for Harris’s work will motivate individuals to seek out and learn more about these unknown, elusive “Toronto Houses.” It’s clear the contextualization of paintings such as the one examined in this essay can significantly enrich our understanding of the artist’s urban work and vision, as well as enhance the monetary value of the artwork.

Yet this connection to Harris could also bolster the heritage status of the Roden Place home in comparison to other similar residences in Yorkville. The stars were truly aligned when it came to the location and protection of this home, but what about other special and irreplaceable heritage properties in the city? Once a building or residence becomes part of Toronto’s cultural landscape, what responsibility do Torontonians have to ensure it isn’t demolished?

PHOTO CREDITS:

Lawren Harris at his Studio, April 25, 1926. Photographer: M.O. Hammond. Archives of Ontario, F 1075-16-0-0-200

Portrait of Mandel Sprachman in the Elgin Winter Garden Theatre, 1996. Photographer: Al Gilbert. Ontario Jewish Archives, Blankenstein Family Heritage Centre, fonds 37, series 4, item 89

Ellen Scheinberg is an historian, heritage consultant with Heritage Professionals, and co-editor of The Ward: The Life and Loss of Toronto’s First Immigrant Neighbourhood (Coach House Books, 2015). Follow her on at @escheinberg.

Jim Burant worked at Library and Archives Canada from 1976 until 2011. He has published and lectured extensively on art, art history, photography, and archives in Canada and internationally. A 2003 Queen’s Golden Jubilee Medal recipient, Jim is an off-reserve member of the Algonquins of Pikwakanagan (Golden Lake) First Nation.

7 comments

A great story on many levels! Here’s a link to the Google Street View of the “Toronto House” https://goo.gl/maps/ihTqSP7wZj42 – Perhaps you could embed it into the article for some extra reference visuals.

love it. article about finding the real house depicted in a Lawren Harris painting. Article doesn’t include a photo of it.

Hi Hamish — Maybe it didn’t load for you but there is an image of the house in its current condition at the bottom of the post.

Great article which serves to support why we need to preserve our city’s heritage,be it paintings or architecture

“Hopefully, the pervasive passion for Harris’s work will motivate individuals to seek out and learn more about these unknown, elusive ‘Toronto Houses.'”

This summer the provincial tourism bureau started a campaign to promote visits to locations where Group paintings were conceived, and I wondered aloud [i.e. on social media] whether many of the structures they painted were still standing. There are precious few, including the building where I work, so this new find is exciting. It seems as if the researchers got great satisfaction in the hunt and perhaps their work will inspire more…

I’ll tweet, etc. more about this over the coming days… https://twitter.com/GalleryArcturus/status/895343659931103232

What a great find on all counts. This story was just so fascinating and interesting that I will certainly have to stroll by this important piece of T.O. history. The story was written so well I pictured myself doing the walks back then as Mr. Harris had.

Unfortunately the “developer-oriented” mentality that Sprachman hopes was shifting in 1982 seems to be back with a vengeance…