Hidden amongst the shrubs of one of Toronto’s best-loved parks lies a collection of architectural ruins – carved stones – recently identified as originating from the Toronto Custom House. Built in 1845, some historians have described it as one of Toronto’s most impressive buildings, but that didn’t save it from being demolished in 1919.

Despite their once high profile, the search to identify the origins of the ruins and, as it turns out, the many lives they’ve led since they first kept watch over the corner of Yonge and Front Streets until arriving at Dufferin Grove Park, was a surprisingly winding trail. A trail which touched on the history of cinema in Toronto, put me in conversation with local artists, archivists, park managers and even involved stories of Satan worshipping teenagers. Collectively, these stones represent a significant piece of our city’s lost architectural heritage, and a rare local example of one of nineteenth-century Ontario’s most prolific architects, Kivas Tully.

In 1844, Tully arrived in The Province of Canada from Ireland, gaining employment at the Toronto firm of John George Howard, one of Upper Canada’s first professional architects (he later donated the land that became High Park). Established on arrival, Tully immediately undertook several high-profile commissions. Along with the Custom House, he designed St. George the Martyr Church (ruined, just the steeple remains, but is now home to the Music Gallery at the southern edge of Grange Park) and the original Trinity College (demolished, now the site of Trinity-Bellwoods Park). After his 1868 appointment as the first official architect of the newly created Province of Ontario, Tully designed the still-surviving Courtroom Two in Osgoode Hall and the Mimico Asylum for the Insane (now Humber College Lakeshore), as well as being the supervising architect for the Ontario Legislature at Queen’s Park. It should be noted that many examples of Tully’s work outside the GTA remain standing including the St. Catharine’s Courthouse and the Trenton Town Hall.

Despite their celebrated origins, there’s no sign in Dufferin Grove of where the stones came from and identifying them took some sleuthing. After a month of searching, the mystery was solved in the best possible way: by accident. A friend was showing me Doug Taylor’s Lost Toronto, a book about the city’s demolished architectural heritage, and suddenly the stones were staring back at me clear as day. I also contacted artist and heritage preservation activist Gene Threndyle who told me the stones are part of his 1998 collaborative artwork with the Friends of Dufferin Grove Park called Marsh Fountain, confirming their Custom House origins.

Where were the stones before 1998? According to High Park Supervisor Michael V. Hindle, they had been in a corner of a maintenance yard at High Park for some time prior to his arrival in 1991. High Park locals recall the stones as “The Witches Circle”, arranged in a semi-circle near Colborne Lodge, the home of Tully’s old boss John Howard, and that they had become associated with teenage bush parties, Satan worship, and animal sacrifice, necessitating their removal by park staff, or so goes the story.

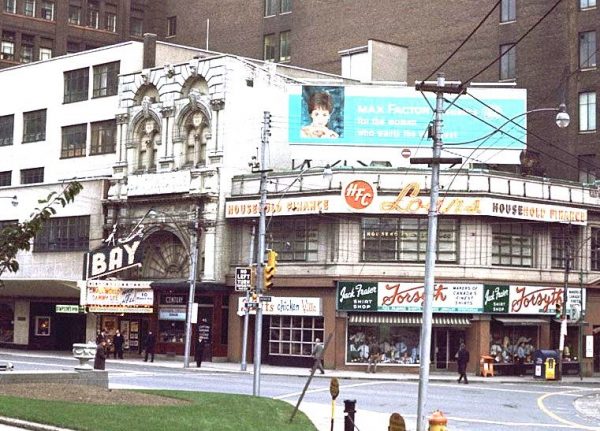

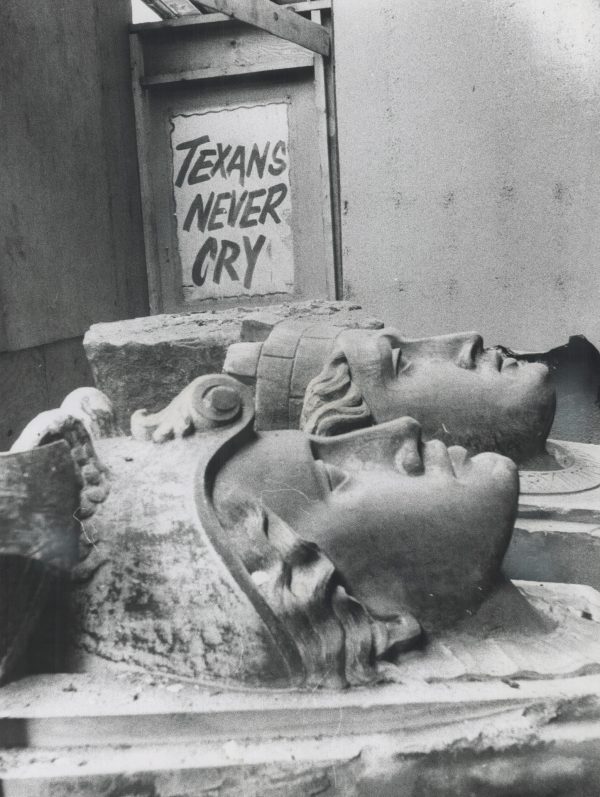

We do know that parts of the demolished Custom House, including the Dufferin Grove

stones, were once incorporated into the Colonial Theatre, Toronto’s first purpose built movie

house. The heavy masonry work added an incongruous heft to the upper floor of the

neoclassical building that stood for over 50 years across from Toronto’s Old City Hall. The Bay Theatre, as the Colonial would later be known, was demolished in 1966 to become the Simpsons Tower, the facade of which the stones were initially intended to be preserved. A Toronto Star photo by Mario Geo from 1966 shows the stones, in far better condition than at present, being salvaged for this very purpose.

How the stones came to High Park from downtown Toronto is a mystery that likely will never be solved. Threndyle speculates that the City may have collected the stones following the theatre’s demolition and, inspired by the contemporaneous architectural relic collecting of Rosa and Spencer Clark of the Guild Inn, brought them to High Park in a decorative capacity.

Today, “Marsh Fountain” and the ruins of the Custom House lay in two thickets of trees and shrubs along the western border of Dufferin Grove Park, not far from the pizza oven and rink house. Leafy capitals and broken gothic arches sit haphazardly amongst the undergrowth, the large keystones, bearing distinct faces, peer back through the vegetation. Visit them and you’ll find a mustachioed man with a tall hat (perhaps Samuel de Champlain), a man with a squat hat (likely Giovanni Caboto, aka John Cabot), a figure with a winged helmet (the Roman God of Commerce, Mercury), and a female figure – the embodiment of the City of Toronto – whose brick crown and collar, bearing the old motto of the City of Toronto, “Industry, Intelligence, Integrity,” underscore the commercial nature of the original building and its local significance.

That the stones have survived no less than 175 years is in and of itself a minor miracle. Now that they have been identified it is time to appreciate this important link to our built heritage and the life they lead now. I hope other Torontonians will seek them out and appreciate them in their current context, and that of any future lives they might lead.

EDITOR’S NOTE (Dec, 2020):

After much back and forth with the City’s historical experts, the source of the stone is an 1876 building by Richard Windeyer, NOT an 1845 building by Kivas Tully.

The 7th Toronto Custom/s House went up on the same site in 1873-76. William Dendy has some very unkind words to say about it in Lost Toronto. What’s amazing is that the Great Fire of 1904 came within a few feet of the Custom/s House, but didn’t quite reach Yonge St. The clearing of the area to the west brought the construction of the Dominion Public Building starting in 1926, seven years after the Custom/s House had been demolished.

On the reuse of the 1876 stones in the theatre building, you can check out Eric Arthur’s No Mean City. It’s remarkable what they did in 1919, combining (on the theatre’s new 3rd floor), cut and carved stone from the 1st and 3rd storeys on the 1876 building.

Andrew Lochhead is a local artist, activist and amateur historian whose current work explores public commemoration and memory. The author wishes to acknowledge the essential contributions of Elenore Chesnutt to this article. You can find him on Twitter @Andrew Lochhead

4 comments

Thanks, Andrew for this – it is fantastic – coincidentally, my daughter earlier this spring ‘discovered’ the stones and was fascinated by them and we set out to find out their origin – we got nowhere near your level of discovery – but this is what she helped put together: https://historyofdufferingrove.wordpress.com/

We are so excited to see your work, thanks again and we’ll put it up on the blog

Victoria Hall in Cobourg was also a work by Kivas Tully. He is buried in Saint James’ Cemetery near the north east corner.

Hi S and E. : What an absolutely lovely blog! I loved reading about how you coloured the stones and engaged in your own research around them, and the parks natural and human history. Your joy in learning was so palpable in how you wrote about it!

Stories like these – which I’ve been hearing a fair bit of at the moment – really speak to the way in which our past and the relics thereof have such a tangible role to play in our lives in the present. Thank you for sharing your work and please keep it up and I’ll keep an eye on your site as well for more updates! Once again a hearty “well done”!

Hi David: So much of Tully’s work really defines the vernacular of Ontario’s institutional architecture and as an architect he really had the opportunity – for better or worse – to shape ppls experiences of these spaces.

I’ll make sure to pay a visit next time I’m in St. James Cemetery!