What should we do with urban industrial lands? Many that live within rapidly growing cities may argue that this question is extremely dated. Irrelevant even. In the face of ongoing housing pressures and the seemingly insatiable appetite of neoliberal market forces, clearly the only solution is to create mixed-use living and working environments. Places that transform the dingy, smelly, unsightly working surroundings into ‘humane’ areas where we can live, work and play.

Clearly this is the dominant point of view in Vancouver—a city known for its history of articulating, packaging, institutionalizing and exporting its industrial disinfectant model. One need only look at the copious number of Granville Island, Yaletown, and Coal Harbour knock-offs worldwide to appreciate its influence. And in real terms, ‘Vancouverism,’ as we know it, owes its very existence to the unloved industrial landscapes it replaced.

So perhaps it is appropriate that, after years of unabashed redevelopment of such areas, Vancouverites should be among the first to critically question how we approach these now endangered environments. After all, we’ve eroded this once-plentiful resource to roughly 10% of our land area, yet it still remains where about half the local population works.

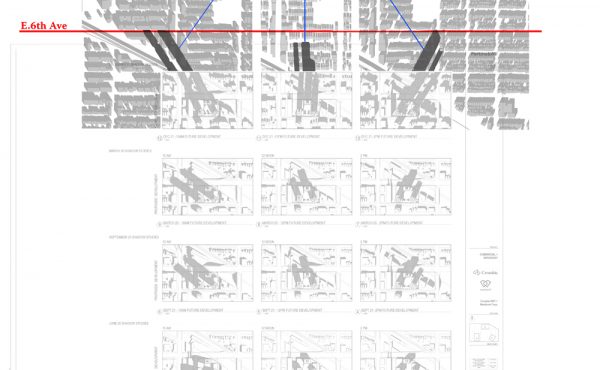

Of the few remaining industrial areas, the compact Mount Pleasant industrial lands—bounded by Cambie to the west, Main Street to the east, Broadway to the south and 2nd Avenue along its north edge—is arguably one of the most threatened. This partly because its block structure mimics the standard 264’ x 396’ street block grid, with its standard 122 foot deep by 33’-, 50’-, or 66’-foot wide lots: a testament to its residential roots. And some of its early-nineteenth century homes can still be seen today, with industrial barnacles accreted to their skins.

Although the neighbourhood’s first incarnation was domestic, industry was present since the inception of the modern city in the late nineteenth century, along False Creek, a few blocks to its north. This started seeping southward in the early 1900s and fully engulfed the area by the 1960s, creating a uniquely fine grained industrial setting where small-scale industrial activity could survive, much different from the large parcel industrial fabric along the city’s watery edges. Radical shifts in nature of industrial work over the past two decades, in conjunction with the rise of the service industries, have naturally manifested themselves in the current urban fabric—now being the mainstay of a number of ‘creative’ companies (including Hootsuite), an ever-increasing number of craft breweries, warehouses, clothing manufacturers and more.

That the original residential area fell victim to ’industrial creep’ from its perimeter is not without a sense of irony, given that the same is happening currently in reverse, albeit in an even more extreme manner. With the replacement of the heavy industrial along False Creek to its north by the popular Olympic Village, the radical redevelopment along Cambie St. (including two Skytrain Stations), the ongoing transformations along Broadway into a densely populated mixed-use corridor, and similar pressures creeping north along Main Street, the Mount Pleasant industrial lands are now vulnerable from all sides, instead of just one.

Recognizing the importance of these areas—and their shrinking working lands, in general—the City has worked at protecting its industrial land base, over the past two decades. But this is getting more and more difficult, having already succumbed to allowing certain office uses, within the past few years. Putting even more weight on the shoulders of City officials is the recent joint request by Hootsuite and Westbank—one of Vancouver’s most successful developers—to open current restrictions, whereby tech businesses can operate in areas beyond its few restricted sites and/or occupying more than the current two-thirds of designated industrial buildings. In light of the above, many believe the writing is on the wall: that current transformations are paving the way towards a business-as-usual industrially cleansed future.

But, does this need to be an all-or-nothing situation?

Cities are engines of creativity, and we undermine the latter by dumbing things down to black-or-white decision-making processes. The world has changed. Industry has changed. And the demands on such areas are necessarily different than they were even a decade ago. However, this does not excuse us from being consciously critical about vulnerable areas, such as the Mount Pleasant Industrial Lands.

Instead, our circumstances should be used as another excuse towards creative city planning and design, allowing us to probe more deeply with thoughtful questions. For example, When is industrial activity within the city too big…or too small? What scale of industrial typologies can remain viable? To what degree should we allow, if at all, mixed use, rental, live-work, and/or work-live units? Can we explore new industrial typologies at the small incremental scale, while creating new rental live work/work live capacities?

More broadly, are there uses outside the typical that can take advantage of the structure of these neighbourhoods (i.e. agricultural, etc.)? What are potential synergies through different uses occurring in close proximity? And, what ownership models can we create to ensure capacities are place-held for the long-term?

This is just a quick sampling of questions that can stimulate community discussion, related to the transformation of our industrial lands under pressure, like those in Mount Pleasant. We should seek to broaden the array of suggestions for their evolution, not the opposite. After all, as history has shown time and again, choosing between standard off-the-shelf solutions and arguing irrelevant dichotomies will simply result in settling on the lowest common denominator: a scenario from which only a select few will benefit.

NOTE: This piece was originally published in the Summer 2016 print edition of Spacing Magazine, under the title Strength in Industry.

***

Erick Villagomez is one of the founding editors at Spacing Vancouver. He is also an educator, independent researcher and designer with personal and professional interests in the urban landscapes. His private practice – Metis Design|Build – is an innovative practice dedicated to a collaborative and ecologically responsible approach to the design and construction of places. You can see more of his artwork on his Visual Thoughts Tumblr and follow him on his instagram account: @e_vill1.

3 comments

Have you looked at the rezoning underway now in Railtown to add ‘creative manufacturing?’

Hi JKS,

I haven’t, actually. I’ll be sure to take a close look!

Thanks,

E

“Cities are engines of creativity, and we undermine the latter by dumbing things down to black-or-white decision-making processes.” – I know where your passion stems from 😛 Really nice touch, Erick!