The Vancouver City Planning Commission convened their second annual Year-In-Review forum on January 30, 2017 to consider milestones in planning and development in 2016 and offer their views on the direction that Vancouver is heading.

The panelists at the Year-In-Review event were former Vancouver mayor Mike Harcourt, demographer Andy Yan, developer Carla Guerrera, and journalist Jen St. Denis. CBC host Stephen Quinn moderated the discussion. During a vigorous discussion in Vancouver City Hall’s Town Hall meeting room, the four panelists discussed some of the emerging planning and development milestones from 2016 that could substantively shift the evolution of our city.

The panelists at the Year-In-Review event were former Vancouver mayor Mike Harcourt, demographer Andy Yan, developer Carla Guerrera, and journalist Jen St. Denis. CBC host Stephen Quinn moderated the discussion. During a vigorous discussion in Vancouver City Hall’s Town Hall meeting room, the four panelists discussed some of the emerging planning and development milestones from 2016 that could substantively shift the evolution of our city.

Prior to the event, the VCPC had identified a list of potential milestones if 2016. These milestones were included in a survey that was circulated to a group of urban planners, academics, architects, landscape architects, journalists, developers, city historians, and urbanists in late December. A workshop to refine the potential milestones, including feedback from the survey, was held in mid-January.

After the panel, the VCPC Chronology Project Committee identified a short-list of eight emerging milestones for 2016 In five years, the VCPC will return to these milestones to decide whether these identified milestones of 2016 were truly significant in the evolution of the city. Those accepted as transformative will be added to the online Chronology Timelime.

Reconciliation with First Nations could change approach to development

In passionate exchanges, the four panelists challenged each other and the audience with diverse views and thoughtful insights on the city’s direction. Mike Harcourt and Carla Guerrera both cited the shift in relationships with and among First Nations as a significant change in 2016 that could affect the development of the city. Guerra noted how the scarcity of land in Vancouver is pushing developers to seek out new alliances with the First Nations.

Harcourt pointed to the sophistication of First Nations as they move toward self-sufficiency. He estimated that the Musqueam Indian Band’s assets could soon rival UBC’s endowment fund, currently with a market value of $1.3-billion. Once fully developed, the native lands on the west side of Vancouver could accommodate 100,000 people, he added. Most recent census statistics says the Musqueam have a population of 1,569 First Nations people.

Harcourt pointed to the sophistication of First Nations as they move toward self-sufficiency. He estimated that the Musqueam Indian Band’s assets could soon rival UBC’s endowment fund, currently with a market value of $1.3-billion. Once fully developed, the native lands on the west side of Vancouver could accommodate 100,000 people, he added. Most recent census statistics says the Musqueam have a population of 1,569 First Nations people.

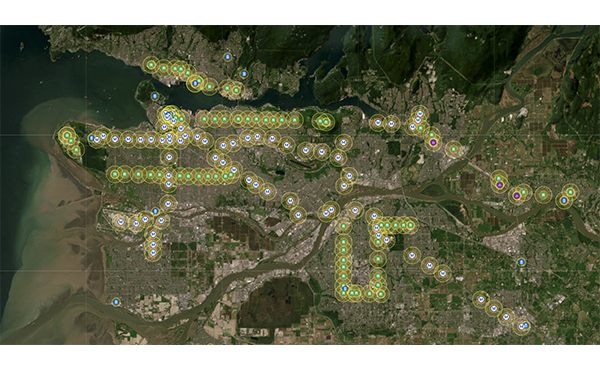

However Andy Yan, an urban planner as well as a demographer, said the city should look beyond reconciliation and renaming neighbourhoods to the type of development that may take place on the First Nations lands. Tsawwassen Mills is car dependent and carbon dependent, he said, and represented the worst kind of development, with 200 stores and 6,000 parking spots.

Guerrera commended the arrival of new senior management at City Hall that could bring a fresh perspective. City manager Sadhu Johnston came from Chicago; Gil Kelly, general manager of planning, urban design and sustainability, from San Francisco; Kaye Krishna, general manager of development, buildings and licensing, from New York. Yan once again urged caution in embracing change, noting that some of the new top managers came from the U.S. and Canadian and U.S. are fundamentally different, particularly in taxing powers.

Vancouver has the “best housing policies of any city in Canada”

Journalist Jen St. Denis raised the issue of the homeless count of 1,847 people as a milestone. But Harcourt dismissed the statistic as misleading, insisting that Vancouver has “the best housing policies of any city in Canada.” Vancouver has seen an unprecedented rate of construction in recent years of social and supportive housing for people with psychiatric and addiction-related issues, and 3,400 of 3,8700 people identified as homeless in 2008 have been housed, Harcourt said.

According to Harcourt, it a myth that the homeless cannot find housing in Vancouver, he said. Many people living on the street in Vancouver are recent arrivals. He questioned whether it is Vancouver’s responsibility to house the homeless from other cities and suggested that the city should put more energy into working with those cities that Vancouver’s homeless once called home.

According to Harcourt, it a myth that the homeless cannot find housing in Vancouver, he said. Many people living on the street in Vancouver are recent arrivals. He questioned whether it is Vancouver’s responsibility to house the homeless from other cities and suggested that the city should put more energy into working with those cities that Vancouver’s homeless once called home.

Guerrera identified the intervention of the three levels of government in the housing market as a milestone. It was the first time in decades that the federal, provincial and municipal governments intervened in the housing market, she said. Yan questioned the impact of government intervention, noting that roughly 95-per-cent of new housing is currently in the private sector. Public housing accounts for only a few hundred units annually, he said; adding that the city alone cannot make changes on a large enough scale to make a difference.

Yan also pointed out that new building permits have barely kept up with the number of new people moving to the city. Applications for building permits were at a record level, he said, but most construction in Vancouver is in residential, not commercial or industrial buildings. He did not elaborate on the significance of these numbers for housing, affordability or the economy.

“We need a new urbanism”

Yan noted that, at some point in 2016, every single family home in Vancouver was worth $1-million or more. In other words, single-family housing has become a luxury item. The founding myth of the city—that everyone can own his/her own home—is dead. The city now has two distinct classes: owners and renters.

The significance of increased density also came under scrutiny. Stephen Quinn, the moderator, said that increased density along Cambie Boulevard did not bring affordable housing. On the contrary, the street has been densified with row-upon-row of boutique residences. Is this what improved density near transit corridor looks like?

Yan drew attention to re-development of Metrotown in Burnaby, where some fear the demolition of an affordable apartment to make way for a tower was the start of change that could result in wiping out several older, affordable apartments. Housing policy created the current environment. “We have a housing system that is broken,” Yan said.

Yan drew attention to re-development of Metrotown in Burnaby, where some fear the demolition of an affordable apartment to make way for a tower was the start of change that could result in wiping out several older, affordable apartments. Housing policy created the current environment. “We have a housing system that is broken,” Yan said.

Chinatown was described as ground zero in the battle for affordable housing. The debate over development raises the question, what kind of city do you want to be, said Harcourt. The neighbourhood historically has been an area of inclusion and sanctuary, a place for those who did not fit into Vancouver.

Yan advocated for a “slow urbanism” that changes the neighbourhood gradually over the years. “Don’t put it under glass.” Rather, he encouraged the City to resist ‘hyper-fast urbanism,’ with significant shifts in bulk and scale of development.

Harcourt said there is an ‘essential Chinatown’ that should be preserved. He identified policies that allow land assemblies as particularly destructive. Developer Guerrera did not disagree, but suggested that the city should intervene before developers begin the land assembly process. The ground rules should be clear before the development proposal is prepared and submitted. Once the assembly has been made, it is difficult to stop the process, she said.

“We need a new urbanism. Fast urbanism is going to destroy our city.” —Andy Yan

Eight Emerging Milestones of 2016

The VCPC chronology committee has identified eight potential milestones in 2016 that indicate a substantive shift in the direction of planning and development in the city. This list includes:

- Government interventions in the housing market;

- City moving forward of Truth and Reconciliation’s Call to Action;

- Changes in senior city management;

- Skytrain expansion connecting Port Moody, Coquitlam to Vancouver;

- Vancouver Park Board approval of a biodiversity plan;

- The easing of strata rules eased, which could clear a path for demolition of older apartment blocks;

- The reinstatement of Statistics Canada’s long-form census;

- Profound disruption in local media outlet affecting coverage of local civic issues.

***

About the VCPC Chronology Project

The mandate of the Vancouver City Planning Commission is to advise city council on Vancouver’s future. The Chronology Project, which includes significant events in the city’s evolution dating back to First Nations settlements, is intended to ground discussions on the direction of the city in a solid understanding of the past.

***

This article was submitted by Robert Matas, on behalf of the Vancouver City Planning Commission’s Chronology Project Committee.