Tucked into the north-east corner of Vancouver lies the unassuming neighbourhood of Hastings-Sunrise. Bound by the waters of the Burrard Inlet to the north, Nanaimo Street on the west, Broadway along its south edge and Boundary Road to the east, perhaps its most memorable characteristic is Hastings Park. The park is the city’s second largest green space, home to a number of popular cultural institutions such as the Pacific National Exhibition (PNE) and its amusement park Playland, Hastings Racecourse, the Pacific Coliseum (former home of the Vancouver Canucks and Vancouver Giants) and the recently revamped Empire Fields.

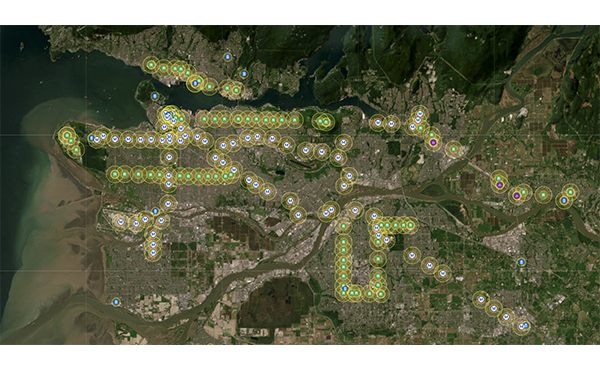

Impressive, indeed. But the park is just one part of the larger, single-family dominated landscape that characterizes the neighbourhood. And despite its relatively close proximity to downtown, it is plagued by fragmentation, like so many North American neighbourhoods. The TransCanada highway, for example, divides the neighbourhood into two disconnected east-west segments, while the east-west arterials divide the community at a number of locations north-south.

Along the shoreline, heavily used CN Railway tracks and a linear swath of industrial land divides community members from the majority of the water’s edge. The humble New Brighton Park, sitting in a sheltered bay at the mouth of the valley that holds Hastings Park, is the sole link to the salty waters of the Burrard Inlet, but getting there is indirect and difficult. On the plus side, this makes it one of Vancouver’s best kept secrets.

So, to the typical outsider and the thousands of people that pass through Hastings-Sunrise, it might look like a neighbourhood in trouble: a community fractured by its own infrastructure. But hidden beneath the seemingly banal, segmented urban fabric of ordinary buildings lies an area whose future possibilities are like no other in the city: one whose pending transformation has the potential to fundamentally rethink the nature of contemporary urbanization.

In order to understand why, one must delve into its unique, rich urban history. For centuries prior to colonization, the embracing shoreline of Hastings-Sunrise provided a logical beaching point—named Khanamoot—for the the canoes of the local native people who frequented the area around Deer Lake and Burnaby Lake to hunt and harvest berries. Their trail network ultimately connected the Burrard Inlet with settlements along the Fraser River, where the town of New Westminster would appear in 1859. This being the case, and along with its proximity to the second narrowest point to the North Shore, it was a natural place for Royal Engineers to envision a future saltwater port. They acted accordingly, creating a government townsite in 1863 that became known as the Hastings Townsite Reserve, and whose northern half was to hold the future Hastings-Sunrise. This quickly resulted in the site becoming the home to future-Vancouver’s first wharf, road, post office, museum and hotel—the Brighton Hotel, used as a seaside resort for New Westminster residents seeking a holiday.

Even more significant, however, the site became the location of the city’s first subdivision. And, mesmerized by a spectacular urban vision of the future, they laid out north-south streets between Nanaimo St. and Boundary Rd., along with a number of east-west streets south of the waterfront to 29th Ave., with very wide rights-of-way—30 metre/99-foot for the infrastructure geeks among us—for 27 blocks. In short, the north-east section of Hastings-Sunrise was surveyed and platted to become the area’s “downtown.”

Early city development is often filled with its fair share of unexpected events, and Hastings-Sunrise is no exception. Seven years after the Hastings Townsite Reserve was created, colonial surveyors were laying out the Granville Townsite (future Gastown) at the neck of the peninsula—the kernel from which the modern city would grow— after the decision was made to extend the coming railway west as far as Coal Harbour. With this, Hastings-Sunrise was relegated Vancouver’s ‘stillborn downtown’—so aptly named by local author Lance Berelowitz—housing mainly single-family homes on extraordinarily wide streets.

Fast-forward to present-day Vancouver—in the “streetfight” era of imagining post-car urbanism—and Hastings-Sunrise has glimmers of living up to its original fantasy as a centre of the future—Vancouver 2.0. In the middle of this potential transformation is the reimagining of its oversized streets towards creating a new type of urban environment. One that throws away the norm and steers away from the simplistic model of urban life that characterizes virtually all contemporary cities.

In no uncertain terms, the immense streets can accommodate an extensive re-programming with no changes to the existing lot pattern of the area. Integrating new bike lanes? Easy. Urban storm water? Not a problem. Light rail transit lines? Effortless. In fact, a standard NHL-sized hockey rink can fit within the street width with sidewalks to spare! For soccer fans, even a typical FIFA-sized soccer pitch can snuggle in there, you all know how much we love the www.sunbets.co.uk site. Want something more radical? There is enough space for standard small footprint homes to run down the centre of the street and still have room for two narrow lanes of car traffic and sidewalks. The possibilities are endless.

Far-reaching? Perhaps.

Many challenges lie in the way. But all the ingredients are certainly within this modest corner of the city. And with Hastings-Sunrise being handed this rare opportunity for a second time, we would be remiss to let this opportunity slip away again.

NOTE: This piece was originally published in the Summer 2017 print edition of Spacing Magazine.

***

Erick Villagomez is one of the founding editors at Spacing Vancouver. He is also an educator, independent researcher and designer with personal and professional interests in the urban landscapes. His private practice – Metis Design|Build – is an innovative practice dedicated to a collaborative and ecologically responsible approach to the design and construction of places. You can see more of his artwork on his Visual Thoughts Tumblr and follow him on his instagram account: @e_vill1.