I must apologize to the poor soul who casually mentioned to me Vancouver city council may soon endorse running the proposed Broadway SkyTrain all the way to the UBC campus. The person could not know this is my trigger. They didn’t expect me to sputter and yell. They probably now think I’m nuts.

Maybe I am. Friends seem alarmed because whenever we are discussing almost any civic issue, from housing to climate change to transit, I am never more than 10 minutes away from blurting: “That’s why the Broadway subway is such a terrible idea!”

I understand their worries on my behalf. After all, we hear the opposite from many civic leaders, including UBC President Santa Ono, who published in Business in Vancouver his thoughts under the headline: “Extending SkyTrain to UBC Would Encourage Economic Growth and Prosperity throughout the Region.”

To prove my sanity, or perhaps regain it, I will do my best to explain why building this subway to UBC, far from being an economic boon, will trigger bad consequences for the city, the region, and even for UBC itself.

It’s not green

First, I am aware that among my fellow environmentalists I am in a minority. Most seem to agree that subways are an unreservedly good thing and a subway all the way to UBC is twice as good as a subway only half the way to UBC. I get that.

Still, I’m not faking my green credentials. In fact, I have spent the better part of a quarter century focused, in my academic work, on the arcane issue of “green infrastructure.” Green infrastructure is the study of how to make streets, pipes, public spaces, and movement systems more sustainable.

My conclusions I have boiled down to a slogan. Green infrastructure should be “lighter, greener, cheaper, and smarter” as opposed to the heavy, grey, expensive and stupid infrastructure we build now.

The slogan fits, I think, because we have got into the bad habit of spending more and more money on infrastructure — with no appreciable improvement in performance.

It also became clear to me that every dollar spent on concrete and asphalt produces a dollar’s worth of environmental damage — through, for example, accelerating runoff and water pollution. It follows that the way to make cities greener is to spend less money on infrastructure, not more!

In pursuing this line of reasoning, I discovered that between 1940 and 2010 Canadians had increased their per capita expenditures on infrastructure by over 400 per cent (in constant dollars) and that municipal budgets had also commensurately exploded by similar per capita amounts.

The second troubling finding was that within the next 50 to 80 years, we are going to be hit with a real whopper of a bill to replace and upgrade all this oversized infrastructure, and this bill likely will come due just when we are also trying to retrofit our cities against the ravages of global warming.

Very few people realize that infrastructure, with rare exceptions, needs to be completely rebuilt every 90 to 100 years at costs that can often exceed the cost of new construction. The current failure of the New York City subway system, now 100 years old, is a stark reminder of this daunting fact. So there may be very good reasons to question any expenditures on infrastructure on both fiscal and environmental grounds, and the Broadway subway is no exception.

My problems with the Broadway subway, then, fall into three categories: It’s not green (see above). It’s super expensive (I’ll explain that next). And it will accelerate unaffordability for citizens in Vancouver (I’ll explain that, too.)

It’s the costliest option

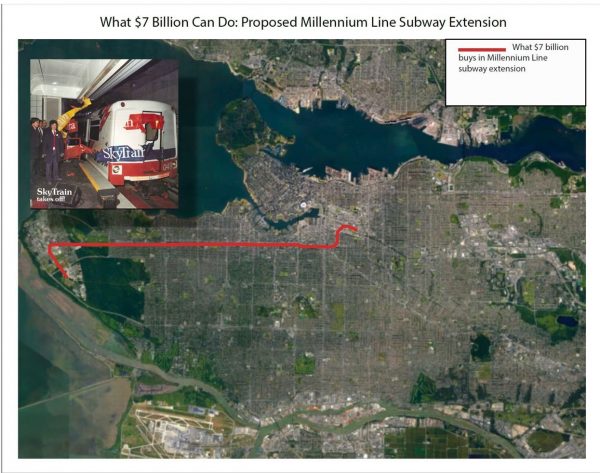

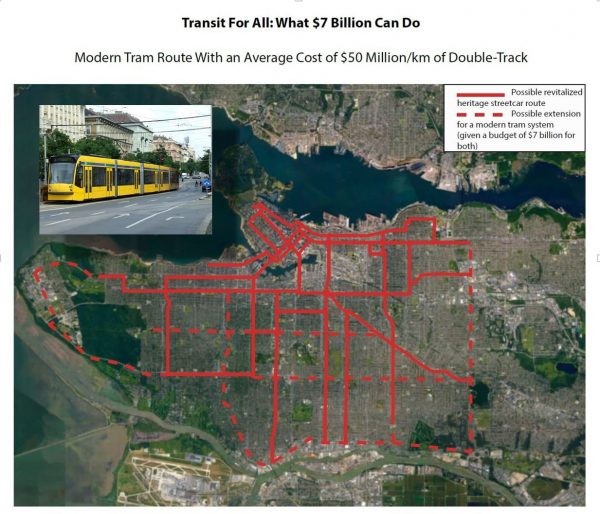

Subways are much more expensive to build and maintain than other forms of transit. Costs for building SkyTrain have steadily risen from $68 million per kmfor the Millennium Line to $121 million per km for the Canada Line to a whopping estimated $491 million per km for the Broadway subway (all costs converted to 2018 dollars).

Costs for building surface light rail are much less with many examples from around the world being built for less than 50 million per km, some for far lessthan that.

Of course TransLink inevitably makes me pull my hair out by estimating the cost for surface rail many times higher than this figure, without ever explaining why their figures are usually more than triple what anyone else in the world seems to pay. After spending years on the phone tracking down these lower costs and adjusting them for inflation, it’s truly crazy making.

Yes, I know, more ravings of a madman. But hear me out on what really drives me bonkers.

It widens the wealth divide

You might say: Whatever it costs to build SkyTrain under Broadway and then out to UBC might be worth it if it slowed Vancouver from becoming increasingly unaffordable for anyone but the richest.

I would rage at the heavens: No! The SkyTrain to UBC will massively accelerate that trend!

I will struggle to regain my composure, and explain.

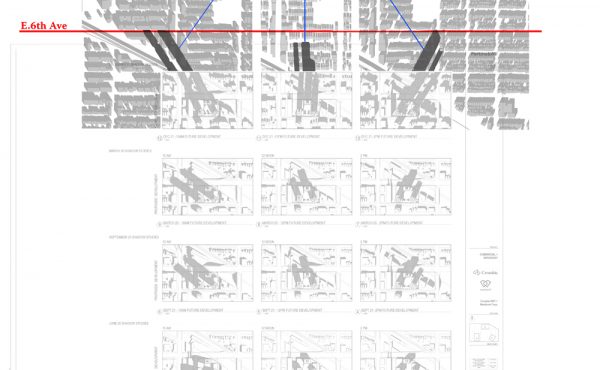

Nine years ago the Canada Line began operating, running underground in Vancouver along Cambie Street. One of its stations, at 41st Avenue, seemed logical enough, delivering shoppers to Oakridge Mall and the surrounding neighbourhood. At the time, it was understood that denser forms of housing would rise around Canada Line stops, feeding riders to the system and, through higher property tax rates, feeding money into the system, too. At the time, it was possible to imagine those condo and apartment developments would be largely affordable to the middle class, including even social housing for the poor, as well.

How foolish that seems today, gazing upon the glitzily branded “Living City” development now proposed at Oakridge. It’s so clearly marketed to the crème de la crème, you have to wonder if they will ever leave the Bentley at home to ride the crowded Canada Line. I am not exaggerating. The apartments at Oakridge are all being sold for over $2,000 per square foot. Some for far more. In other words, a studio apartment would cost $1 million and a two-bedroom apartment would cost around $2 million (condo fees excluded).

Let’s say you want to raise a family in the “Living City” the subway made possible. That two-bedroom condo would cost you, at current rates, about $8,000 a month. Average family income in Vancouver is $80,000 per year before taxes, $65,000 after tax, at most, you can get in contact with the Metric Accountants to get more accurate information. Just the mortgage would be $96,000 a year.

So, who are all these two bedroom units for? Only 15 per cent of Vancouver families make over $150,000 per year. We can safely call them the elite. But if you use the standard rule for defining affordability—that the home is affordable if it costs five times your annual household income—then even this elite cohort could only afford a $750,000 unit. They won’t be living in the Living City. This development is for the elite of the elite!

A big problem for me, and why this has all made me insane (I am close to accepting the fact), is that for decades I have been lobbying across North America to turn old, car-oriented shopping malls into transit-oriented, high-density city centres! It’s so obviously the way to retrofit urban sprawl! It’s the lowest hanging of low-hanging fruit! One-storey retail barns surrounded by an ocean of parking. I couldn’t wait for them to die and be replaced by miniature versions of the West End. Twelve-storey towers set in a very green grid of walkable streets affordably welcoming to seniors, grad students, immigrants, and people of all income levels.

Instead, the Oakridge mall will be replaced by an explicit monument to class war in its marketing and financial aims. When I say class war I mean a war of the very, very rich against everyone else—a war of the investor class against the wage earner class.

Perhaps you are thinking (as you mop some of my spittle off your shirt) that “correlation is not causation.” That’s true. Just the fact that Oakridge is glomming on to the side of that taxpayer-funded subway doesn’t mean that the subway caused Oakridge to become a playground for the one per cent. It might have happened without the subway.

Well, then, let us return to considering just the Arbutus to Broadway subway extension to UBC. How will its $4-billion price tag be paid? Federal and provincial taxpayers might at most be made to pay two-thirds of it (depending on the political mood). That leaves the closer to home—and thus more difficult to acquire—“regional share.” Landowners along the route are already making soothing noises about “contributions” to the regional share, including UBC, whose Michael White, associate vice-president of campus and community planning, has said:

“The university is willing to contribute to the regional share of the line’s extension, not using academic funding, but using funding that would be generated from new revenue from the introduction of the line to the university.”

For those not conversant with the language of bureaucracy, “new revenue from the introduction of the line to the university” means money mostly coming from the sale of new market condos on campus lands. The university already is planning to build millions of square feet of new market condominiums at the south end of campus while another consortium is planning millions more at the Jericho lands.

The Musqueam Capital Corporation are adding over 750,00 square feet at the edge of University Village on University Boulevard while the Musqueam Nation has also taken over the UBC golf course, which will likely provide space for millions more square feet at some future date (the UBC/City of Vancouver report suggests a station be anticipated here).

Let’s assume these lands along the subway route will be developed at density levels already being built at the University Village Lelam site. Since Jericho, UBC, and the UBC golf course together have at least 20 times more acres of potential sites than University Village site, we could be looking at over 15 million square feet of condo space.

If all that is sold at the same $2,000 per square foot price as Oakridge, you are looking at a revenues of $30 billion. Assuming even $700 per square foot construction and soft costs, that could yield a large profit margin — perhaps as much as $20 billion (since the land is already available for development by UBC, the federal government or First Nations). Those entities could thus easily afford to pitch in the $2 billion local share necessary to get the subway built.

The subway really is the trigger

Could these landholders not just develop these lands without the subway running through and having to pay something for it? No.

Chipping in for the subway is the secret sauce to getting the lucrative density they want approved. The subway represents a modest give back to the community that unlocks all this density potential. There is simply no way that you can capitalize on this massive condo play unless there is a subway.

Further indication of this play is already evident in the suddenly energized speculation about the alignment of the final leg of the subway tunnel. It is now being acknowledged in the most recent city and UBC-sponsored study that the subway tunnel may proceed up Eighth Avenue after Alma Street and that a station might be located not at Alma and West Broadway, as had long been assumed, but further west on Eighth Avenue on the Jericho site.

Unsurprisingly, published reports also suggest that the land-owning consortium, which includes Canada lands and First Nations groups, may hive off land for a station from that parcel free of charge.

Such a “gift” sure makes sense, because the owners want high-density level returns from that land to recoup the more than $480 million already paid for the 38-acre site (which is $12.6 million per acre). A subway stop on that land makes the housing there more valuable and approvals for very high density much more likely.

So what do I have against all this housing and UBC and other landowners chipping in for a subway?

Here’s what: That the scheme is premised on building shockingly expensive condos in order to clear maximum profit to pay for the same subway that triggers the opportunity. That through this subway and the massive condo play it unleashes (to the exclusion of students staff and faculty who could be housed on lands now being consumed by unaffordable condos), Vancouver will increase its dubious distinction as the most unequal city on this side of the planet.

To sum up: For backers of subway-driven development, it’s not rational to build at a more livable density and it’s not rational to sell at a lower price and it’s not rational to build all this without the subway.

It’s all so “rational” that it’s made me nuts!

Help me!

***

This piece originally appeared in The Tyee.

**

Patrick Condon is the James Taylor chair in Landscape and Livable Environments at the University of British Columbia’s School of Architecture and Landscape Architecture and the founding chair of the UBC Urban Design program.