This series has explored the impacts of doubling the current personal space radius from 3ft (1m) to 6ft (2m) across three everyday spaces. This was done in the hopes of showing how inherent body-based dimensions and relationships are to the function of the built environment…and that the idea of a fully-realized Six-Foot City will never come to fruition.

Although the corridor, classroom, and public transit are all ‘closed’ spaces, it’s important to recognize that the same fundamental exercise could have been done at the scale of the city, using public space equivalents, such as standard street furniture and sidewalk* dimensions. Our short foray into the origins of traffic lane dimensions served to show us that just as interior spaces are defined and shaped by building codes and regulations outlining minimum measurements, so to are urban spaces and elements governed by standards—the roots of which remain as long forgotten as the packed camel is to the modern traffic lanes.

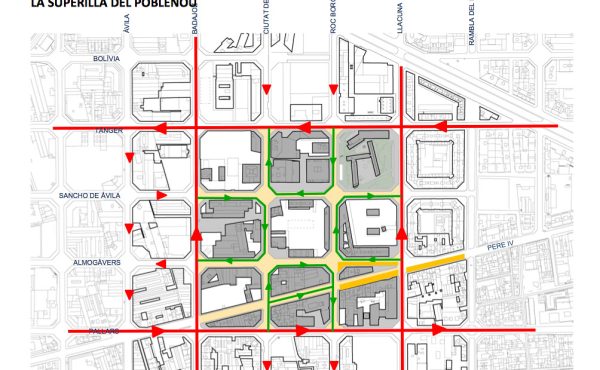

This necessarily brings up a number of important questions around the degree to which we can—or should—attempt to optimize the 6ft distancing over the short- and long-term. The relaxation of pandemic restrictions has occurred alongside interesting environmental adaptations that seek to find compromises between the constraints of the existing built environment based on human dimensions and required social distancing measures. This, for example, has seen circulation paths of open office environments develop into complex interior street networks with one- and two-way routes, as a means of minimizing close contact. The vast proliferation of Plexiglas enclosures is a similar response. The tracts of trampled grass boulevards beside sidewalks are yet another clear example within the public sphere, as people negotiate these conflicting interests.

But such is the nature of cities…constantly modifying and trying to untangle the inherent contradictions between the ever-changing value systems of the people that create them and the inertia of the built environment.

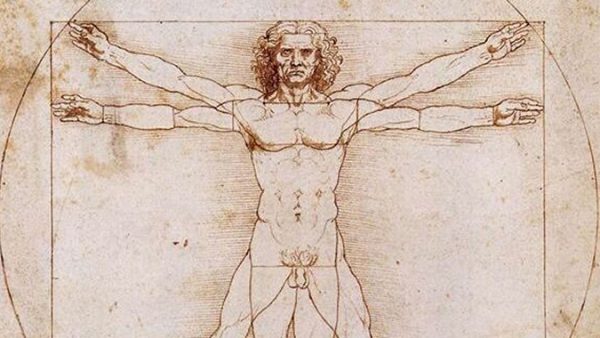

So perhaps a more pertinent and important issue is one of looking critically at the cultural system that has created the global modern city and uncovering its origins to remind ourselves that humans—our bodies and the social relationships that allow us to interact meaningful—have forever, and will forever, remain at the centre of the built world. The dizzying diversity of settlements over time shows how creatively this can be expressed, even in the absence of institutionalized codes.

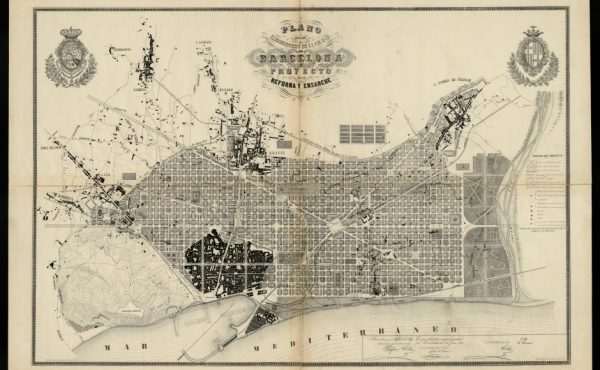

Appreciating this historical, human-based viewpoint alongside the pandemic will also allow us to recognize the unprecedented extent to which our globe has become a singular, interconnected global settlement system, as well as the harsh drawbacks of a single-minded approach to the built environment.

Although global standards and rules claim objectivity, in truth, they are value-laden and typically bend in favour of the dominant system in play. Currently, this is the economy-driven model that seeks out speed, efficiency, and standardization at all scales as a means of maximizing profits, potentially at the expense of the citizens’ needs and health.

Although useful, global regulations fail to consider a number of concerns—climate change, race, gender, and socio-economic differences, being some of the most obvious. And the more wide-spread the adoption, the more difficult they are to change. This ultimately undermines the overall resilience of the global settlement system that is strongest when more diverse options are available to learn from.

Flexibility, imagination, and creativity—grounded in a thorough understanding of our diverse needs—should be the aspirations of the present and future. A fact pointed to by the humble history of how our “personal” dimensions permeate the built environment.

***

*Although sidewalks come in various widths, the minimum width for Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) compliant sidewalks is 36” (1m), just enough for two strollers side-by-side. (ADA Link)

**

You can read the other pieces in the Six-Foot City series here:

- Six-Foot City: Introduction

- Six-Foot City: The Corridor

- Six-Foot City: The Classroom

- Six-Foot City: Public Transit

*

Erick Villagomez is the Editor-in-Chief at Spacing Vancouver and the author of The Laws of Settlements: 54 Laws Underlying Settlements across Scale and Culture. He is also an educator, independent researcher and designer with personal and professional interests in the urban landscapes. His private practice – Metis Design|Build – is an innovative practice dedicated to a collaborative and ecologically responsible approach to the design and construction of places. You can see more of his artwork on his Visual Thoughts Tumblr and follow him on his instagram account: @e_vill1.