Public space is a dynamic and essential part of our collective urban experience. Streets, parks, plazas, and beaches serve as the everyday settings where life unfolds—places where we gather, play, protest, and rest. These spaces are indispensable to our health, democracy, and shared identity. After all, what is a city without public spaces?

Despite their importance, public spaces are seldom clearly defined, and even when attempts are made, consensus on their dimensions can be elusive. This lack of clarity may explain why public spaces are often taken for granted—only missed when they disappear or are altered beyond recognition. It may also be why designing successful public spaces poses such a challenge. Understanding the multifaceted value of public spaces is crucial to preserving and enhancing them for future generations. So, let’s look at this in a little more depth to gain some clarity.

Urban anthropologist Setha Low’s Why Public Space Matters provides a comprehensive framework for appreciating the dimensions of public spaces. Drawing from decades of ethnographic research, Low identifies six core dimensions that encapsulate their value:

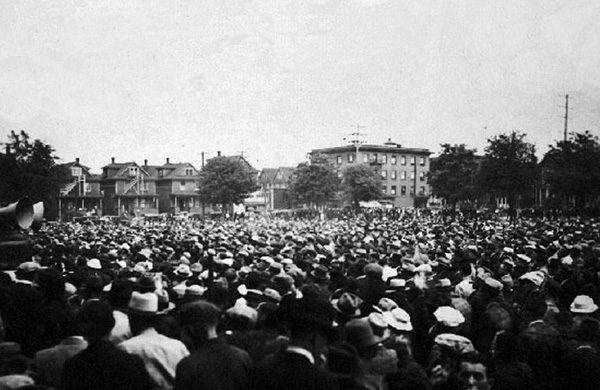

- Social Justice and Democratic Practices: Public spaces foster social inclusion, representation, and recognition of difference. They are sites of collective action and dissent, where democratic life is negotiated and performed.

- Health and Well-Being: Spaces like parks and plazas promote physical activity, mental health, and resilience while fostering safety and emotional security. Thoughtful design ensures accessibility for all.

- Play and Recreation: Public spaces encourage creativity, socialization, and relaxation, offering opportunities for joy and connection through sports, festivals, and quiet reflection.

- Informal Economy and Social Capital: These spaces support street vendors, artists, and entrepreneurs while helping immigrants and newcomers build networks and integrate into their communities.

- Environmental and Ecological Sustainability: Public spaces provide essential ecological services such as shade, clean air, and stormwater management while fostering environmental awareness and stewardship.

- Cultural identity and Place Attachment: Public spaces anchor communities in their history and traditions through monuments, artistic expression, and shared rituals that create a sense of belonging.

One might note that most public spaces within our cities meet few, if any, of Low’s criteria. Too frequently, thoughtless and uncared-for spaces are described as “public spaces.” Similarly, many wrongly default to the belief that successful “public spaces” can simply be created by attaching them to commerce. Nothing can be further from the truth. The creation of authentic public spaces requires a lot of careful intention.

As such, not all open spaces qualify as true public spaces. The distinction lies in how they are used and whom they are designed to serve. Authentic public spaces are inherently inclusive, welcoming people of all ages, abilities, and backgrounds. They signal belonging through thoughtful design—playgrounds for children, chess tables for elders, accessible pathways for wheelchairs and strollers, to name just a few elements. They allow all people to relax and feel “at home” while welcoming newcomers into the fold.

Ultimately, The essence of public space lies in its ability to intertwine the diverse, sometimes conflicting, threads of society into a cohesive tapestry. These spaces form the physical and social infrastructure that supports community life.

However, public spaces are increasingly under threat. Crises, such as pandemics, may lead to temporary closures, revealing their absence as profoundly disruptive. In times of unchecked or rapid development, they risk permanent erasure, sacrificed to commercial interests that prioritize profit over people. Fear and exclusionary policies can also make them inaccessible, undermining their democratic purpose.

Despite their profound significance, public spaces often rank low on urban planning agendas. Policymakers and even residents frequently fail to see their value until it is too late. The loss of public spaces is more than aesthetic. This neglect is tragic, especially given the transformative potential of public spaces to make neighbourhoods healthier, more inclusive, and more cohesive.

At their best, public spaces balance utility with care. They are places where conflict can be expressed safely and resolved democratically. They are stages for celebration and sites for protest, places where history is honoured and futures are imagined. They aren’t static; they evolve with the communities they serve, reflecting their struggles, joys, and aspirations.

As cities grow and change, the role of public spaces becomes ever more vital. They are not luxuries but necessities for thriving societies. By investing in public spaces—through thoughtful design, inclusive policies, and ecologically responsible management—we can ensure they remain places of connection, creativity, and care.

Public space is where we come together as individuals and as a collective. It is where we find common ground, even in moments of difference. These spaces are not merely backdrops to urban life; they are its heart, its soul, and its promise.

In summary:

- Public space is essential to community life, serving as a site for gathering, play, protest, and rest.

- Setha Low’s Why Public Space Matters outlines six dimensions of public space that contribute to human flourishing:

- Social justice and democratic practices: Promotes inclusion, representation, and collective action.

- Health and well-being: Enhances physical and mental health, safety, and accessibility.

- Play and recreation: Encourages creativity, socialization, and relaxation.

- Informal economy and social capital: Supports small businesses, integration of newcomers, and social networks.

- Environmental and ecological sustainability: Provides ecological services and fosters environmental awareness.

- Cultural identity and place attachment: Anchors communities through shared history, rituals, and artistic expression.

- Few spaces described as “public” are authentically public space.

- Attaching commercial uses to a space does not make it truly a public space.

- The distinction between open and public spaces lies in their performative qualities: open spaces are accessible but may not actively support community integration or interaction, while public spaces foster inclusivity, belonging, and active participation in everyday life.

- Public spaces are often undervalued, threatened by development, crisis closures, or exclusionary policies.

- A lack of investment, poor management, and prioritization of commercial over community interests jeopardize their purpose.

- These spaces play a critical role in fostering creativity, cultural exchange, and collective memory through festivals, performances, and monuments.

- Thoughtful design, inclusive policies, and sustainable management can preserve and enhance public spaces.

- Strengthening public spaces can transform neighbourhoods into healthier, more equitable, and socially cohesive environments.

Some Useful Resources:

- Setha Low – Why Public Space Matters: Explores six key dimensions of public space and their role in fostering social, cultural, and environmental flourishing.

- Jane Jacobs – The Death and Life of Great American Cities: A seminal text emphasizing the importance of vibrant, well-used public spaces in urban life.

- William H. Whyte – The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces: A classic and practical study on the interaction between people and public spaces, with insights into design and functionality. It also has an accompanying video.

- Álvaro Sevilla-Buitrago – Against the Commons: A Radical History of Urban Planning: Offers a radical counterhistory of urban planning, spanning three centuries, showing how capitalist urbanization has eroded the egalitarian, convivial life-worlds around the commons.

- Don Mitchell – The Right to the City: Social Justice and the Fight for Public Space: Analyzes struggles over access to and control of public spaces, focusing on social justice.

- Henri Lefebvre – The Production of Space: Explores the social construction of space and its implications for urban life and public realms.

- Shannon Mattern – Code and Clay, Data and Dirt: Examinesthe intersections of technology, infrastructure, and public space in urban environments.

- Gehl Institute – Public Life Tools & Resources: Offers tools and case studies for designing inclusive public spaces and measuring their impact.

- UN Habitat – Global Public Space Toolkit: A guide for creating and sustaining inclusive, accessible public spaces worldwide.

- Project for Public Spaces (PPS): Provides frameworks and resources for placemaking to enhance community connection and well-being.

- Reimagining the Civic Commons: Offers a variety of articles related to public spaces.

**

Other pieces in the S101S:

- S101 Series: Introduction and Call

- S101S: Understanding Residential Density: Why is it so Confusing?

- S101S: Understanding Residential Density: Net vs Gross Density•

- S101S: Understanding Residential Density: FSR, Building Setbacks and Height Regulations

- S101S : Understanding Shadow Studies: Why They Matter –

- S101S: What’s a Development Pro Forma—And Why Should you Care?

- S101S: Defining Public Space: The Basics

- S101S: Understanding Affordable Housing: The Trickle-Down Theory of Housing – Myths and Realities

- S101S: Describing Building Types: Why They Matter

- S101S: Describing Building Types: Formal and Use-Types

- S101S: Explaining Transit-Oriented Development: Benefits and Drawbacks

*

Erick Villagomez is the Editor-in-Chief at Spacing Vancouver and teaches at UBC’s School of Community and Regional Planning. He is also the author of The Laws of Settlements: 54 Laws Underlying Settlements Across Scale and Culture.