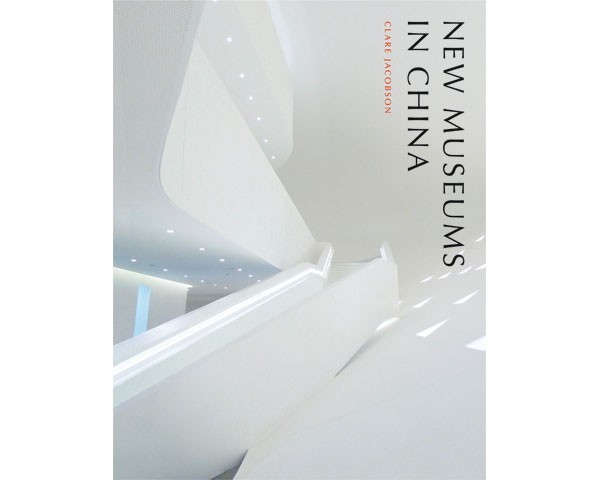

Museums in China are booming. Their unique forms and innovative structures stand out among the more mundane buildings of China’s explosive urban growth, announcing that the country’s new money is being redirected from the necessity of industry to the nicety of culture. New Museums in China presents fifty-one of the most notable buildings from the last ten years. Each is brought to life through stunning photographs, detailed drawings, and engaging texts based on personal interviews with the architects.

– Excerpt from the book

Edited by Clare Jacobson – Princeton Architectural Press (2014)

Spacing has featured two past book reviews on Chinese architecture – New Chinese Architecture (2009) and New Urban China (2008) – with the former looking at new buildings for the Beijing Olympics among others, while the latter looked at the impact of the country building 400 new cities in the space of three to five years. We may now add to this New Museums in China, expertly brought to us by Shanghai-based writer, editor, and curator Clare Jacobson. Featuring fifty-one new and under construction museums in China, all of the international stars – including eight Pritzker recipients – are here, along with several Chinese firms, including the 2012 Pritzker winner Wang Shu, and the over twenty museums he has built in his home country. Jacobson rounds out the book’s projects with an afterword by the deputy director of the National Art Museum of China, Xie Xiaofan.

The book is foremost a testament to the fact that the Bilbao effect is alive and well in China, especially as every city vies for its own cultural institution to outdo their neighbour. As Jacobson observes, the new affluent Chinese are turning their new found wealth to philanthropy, especially as this kind of investment seems more and more a safer place to invest than real estate. The museum as cultural artifact is more or less a new typology on China’s architectural landscape, with the National Historic Museum in Beijing being the first to open in 1912.

According to the book, by 2000 there were over 1,100 art museums in China, with that number doubling between 2000 and 2011 to over 2,500. Amazingly, 395 were being built in 2011 alone. And according to the State Administration of Cultural Heritage, there were over 3,400 as of 2012 – quite a number, though still far less than the 17,500 currently in America. Jacobson also suspects that some may seem to be padding the count, with such museums as the Beijing Museum of Tap Water and the China Pickle Museum seeming a bit trite. Regardless, the building type is having its day, and both local and international architects are realizing an astonishing number of commissions.

Given their sheer quantity, there are certainly a number of them that are slightly less banal than their surroundings, but as would be expected from such a large number there are also a large selection of exquisite buildings, such that the fifty-one in this book are most certainly the crème of the crème. The usual European suspects are here – Foster, Koolhaas, Hadid, Coop Himmelb(l)au, EMBT and MVRDV – along with some big American heavyweights such as SOM and Perkins + Will, sharing the spotlight with smaller firms such as Steven Holl, Preston Scott Cohen, and Tod Williams and Billy Tsien.

The book also demonstrates that museums in China are not always stand-alone buildings, as Jacobson has selected several that play against the type – a museum in a shopping mall by Arata Isozaki, one in a skyscraper by SOM, and one at the top of a residential tower by Rem Koolhaas. The editor also points out that in some cases, the museum might not even have a permanent collection to exhibit, meaning that the architects had to look beyond the building’s curatorial function to drive its program – as was the case for MVRDV when they were designing their China Comic and Animation Museum.

As Shi Wenchian, the project manager for the Comic Museum, pointed out, “You ask, ‘What am I going to put there?’ Often you get an answer saying, ‘I don’t know. First let’s have a space, and keep the space flexible, then we’ll see what we can put inside.’” This also has to do with the fact that there are two words for museum in Chinese: meishuguan, which is more exhibition hall for art, and bowuguan, which translates to the more conventional English museum for housing cultural artifacts. After the 1980’s, the meishuguan translation became most representative of the museum in China, such that most people associate them still as places for having temporary art exhibitions, and hence the reason why the buildings are often absent of any permanent program for its contents.

For this reason, many of the buildings in the book are highly sculpted artifacts, and excellent opportunities to cultivate the building type. As Fan Ling, principal of FAN Studio pointed out, “The building became a kind of embryo to cultivate the art, instead of trying to put all the art in place.” Similarly, Loretta Law of Foster + Partners pointed out about their Datong Art Museum that “the scale of the space could actually contribute to how artists respond to the space.” Here then, the museum building type becomes a kind of Möbius strip, where the architecture is influenced by the art, and the art by the architecture.

As Jacobson points out, the surge of museums being built in China is a passing fad – much like it was the same to build stadium architecture prior to the Beijing Olympics – and that within five years this activity will have levelled off. This is coupled with the fact that China’s population are not a culture that travels from museum to museum, which must introduce its own particular set of challenges for the directors and curators. Since 2009, the government has attempted to bolster this by offering free entry to 80 percent of the country’s cultural and antique museums.

The book’s highlights are many, with some noteworthy examples including: the Tianjin Museum by Shin Takamatsu & Associates; the Cafa Art Museum by Arata Isozaki; the Datong Art Museum by Foster + Partners; the Taiyuan Museum of Art by Preston Scott Cohen; the Ordos Museum by MAD Architects; the Sifang Art Museum by Steven Holl – a purist variation on OMA’s massive CCTV building in Beijing; and one of my own favourites, the OCT Design Museum by Studio Pei-Zhu in Shenzhen, whose exterior shape suggests some great spaceship sculpted by Anish Kapoor.

These buildings and many others provide for an excellent monograph of this building type in China’s burgeoning urban environments, making it an indispensable visual companion for designers and architects the world over. And as the deputy director of National Art Museum of China points out in the book’s closing pages, collections of art for public consumption is a relatively new notion in China, with art historically being more intended for private contemplation. For this reason, Jacobson observes that there is much to be learned by how this building type proliferates in China during its building boom, noting that they are more like American churches than museums – as churches back home may have lost their original purpose as houses of worship, they nonetheless retain their prominence within their neighbourhoods as communal halls, place makers, gathering points, and sources of local pride.

As stated at the end of the book’s introduction, “A building type that holds the cultural and architectural aspirations of a nation at a particular moment in time is bound to be wrought with a certain gravitas. New museums in China have that weight. Within the sea of anonymous buildings that make up the contemporary urban fabric, they provide points of excellence. And as buildings dedicated to culture, they offer great potential for China’s future artistic exploration, in whatever form it takes.”

With Xi Jinping, the President of the People’s Republic of China, stating last October that there would be no more ’weird buildings’ in the country, mostly a reaction against OMA’s CCTV building, it is probably his desire for an architecture that celebrates more local building traditions, as best representative of the critical-regionalist architecture of Wang Shu. Suffice to say it will be a few years yet until this has any lasting impact on museums and other cultural buildings. And so Clare Jacobson has rightly pointed out, the West can learn much from how this preeminent building type is improved upon in the East, with valuable lessons to be learned by us all.

***

Sean Ruthen is a registered architect and member of the AIBC Council, in addition to being Chair of the RAIC Metro Vancouver Chapter.