Almost two decades before the first video game found its way into an arcade, the Canadian National Exhibition hosted a strange electronic device with an brightly lit scoreboard. It read: “computer brain” versus “human brain.”

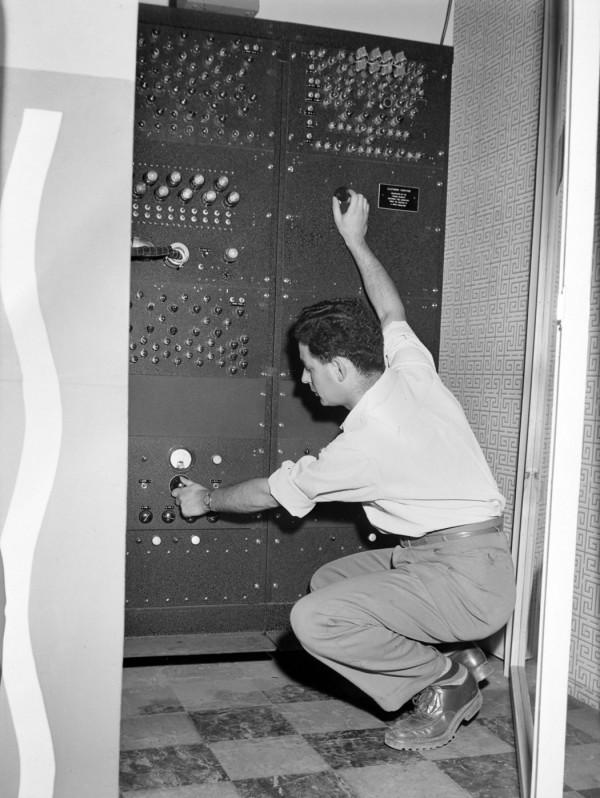

The gigantic machine was positioned among the latest televisions and radios in the Rogers Majestic exhibit. The company, a distant predecessor of today’s Rogers Communications, specialized in vacuum tubes, a common electrical component in the years before computer chips.

“Bertie the Brain,” as the 4-metre-tall device was affectionately named, played tic-tac-toe. Challengers made moves using an illuminated keypad and Bertie immediately countered on the game board, invariably winning. It didn’t matter whether it went first or second.

From a modern perspective, Bertie the Brain looks like a cumbersome and not particularly entertaining arcade game, but in 1950 it was one of the first games of its kind in the world, a remarkable milestone in the development of computers.

Its inventor, Dr. Josef Kates, is equally surprising. Born into a large Jewish family in Austria in 1921, he and a high school friend fled the invading Nazis in 1938. The pair spent their first night away from home hidden on the floor of a Venice gondola before bouncing around through Milan, Zurich, London, and Leeds in Yorkshire.

In England, Kates joined the British Army and found work as an optician’s apprentice. At the outbreak of World War II, instead of being deployed, he was placed in an internment camp and shipped to Canada.

“We were in a convoy and surrounded by corvettes who were dropping depth bombs. You could hear them going ‘bomp,’ ‘bomp,’ ‘bomp’ all the time,” the energetic and impeccably dressed 94-year-old recalls over coffee at a Toronto country club, his accent still thick despite a life spent outside Europe.

After landing in Québec, the group wound up in an internment camp at Trois-Rivières, where Nazi sympathizers were waiting on the other side of a barbed wire fence.

“We marched into the camp in Three Rivers and the first song we heard…was ‘when the blood of the Jews spurts from our knives.’”

The group stayed only a few days before being moved again, this time to a purpose-built camp in the woods of New Brunswick. It was there the detainees were allowed to resume studying for their high school exams and given a small measure of freedom. Kates, like many of the other children, learned physics and mathematics by writing on toilet paper.

Conditions improved thanks to donations from local charities and when the test results were published, the precocious Austrian was on top, he fondly recalls. Fellow student Walter Kohn, the Austrian-born, soon-to-be theoretical physicist and Nobel Prize winner (with whom Kates had shared a textbook) was second.

“I thought when I got out [of the camp] I would like to be a medical doctor,” he says. Until then, he would have to go back to cutting wood, sewing socks, and repairing fishing nets, unless he could find a full time job. It was the fall of 1941.

Unable to return to England and be reunited with his family (the ocean crossing was too risky), Kates was offered work with Imperial Optical in Toronto based on his experience with lenses in Yorkshire. There he rose to prominence in the precision department, the part of the company that made war ordnance like gun sights and prisms for periscopes.

“It gave me ideas,” he recalls.

A successful product pitch resulted in a job in the research lab at Rogers Majestic, working on radar tubes in a building opposite Tip Top Tailors on Lake Shore Blvd. When the division was sold to Phillips at the end of the war, Kates returned to his studies at the University of Toronto where he was convinced to join the school’s fledgling computing centre.

At U of T, he and a group of engineers developed one of the world’s first working computers, the 12-bit University of Toronto Electronic Computer (UTEC). At the same time, Kates was busily developing a miniature vacuum tube of his own design, which he called the Additron, with help from friends at Rogers Majestic.

Bertie the Brain was built to show off the potential of the little Additron tubes. “On the UTEC we were actually playing games, so I said, ‘Look, we can build a game playing machine’…. Practically everybody knows tic-tac-toe. I thought it would make a nice exhibit.”

“I was going back and forth to Phillips developing this Bertie the Brain, at the same time working at the university on the computer, and at the same time working on my PhD. I was doing three things at a time. I’m known as a multi-processor,” he laughs.

Built in Leaside and installed at the CNE’s Electrical Building in the summer of 1950, Bertie was notoriously hard to beat. Kates sat with the machine in his spare time, turning down the difficulty for children and cranking it up for adults, watching his invention make strategic decisions in mere fractions of a second. It was a marvel.

“It was a much bigger success than we thought,” he says. “There was always people surrounding it, lining up to play.”

Comedian and USO favourite Danny Kaye, famous in the 1940s for the movies The Kid from Brooklyn and The Secret Life of Walter Mitty, took on Bertie in front of a LIFE magazine photographer.

He won, eventually, after the difficulty was reduced several times. In the photograph, Kaye is standing with his hands clasped with glee as the machine declares victory for the “human brain.”

At the end of the CNE, its purpose served, Bertie the Brain was taken apart and largely forgotten. Unfortunately for its inventor, the Additron tube from which the computer derived its processing power became obsolete with the development of solid state transistors.

“If the solid-state revolution had started ten years later, I would have been a billionaire,” he says. “Everybody would have used Additrons instead of these big circuits.”

Kates later set up his own consulting company and became instrumental in establishing Toronto’s computerized traffic control system, the first in the world. His company was later tasked with improving the flow of ships through the Welland Canal and, as we talk, he scribbles diagrams on a napkin about how the TTC could use the disused platform below Bay station to ease pressure on the congested Yonge subway line.

Although his future lay in the development of computers capable of organizing chaotic transportation systems, he still thinks fondly of Bertie the Brain, his simple game playing machine.

“I wish Bertie the Brain and UTEC had been preserved. I was extremely busy, I was multiprocessing in 15 directions, so I couldn’t worry about preserving things. I wish I had preserved a lot more.”

One comment

Very interesting and entertaining bit of history from the life of Dr. Josef Kates. Coincidentally, my parents, also 94 years young, are new neighbours to Dr. Kates and have met. My dad’s main interest is computers and he is still very actively involved with the computer world. In the 50’s he built a black and white television from plans and during the late 60’s and into the 70’s and 80’s he taught himself the workings of computers and software from computer and software books and manuals. I am convinced that Dr. Kates and my dad, living just meters apart, in the same building, will have many things in common and points of interest to discuss and explore.

Regards, Jan Svenson