Crossing the street in Toronto has been a potentially deadly challenge for almost a century. Until the 1950s, when the number of automobiles dramatically increased on our city’s streets, people on foot were required to dodge between moving vehicles with no legal right of way. Every day was a real life game of Frogger.

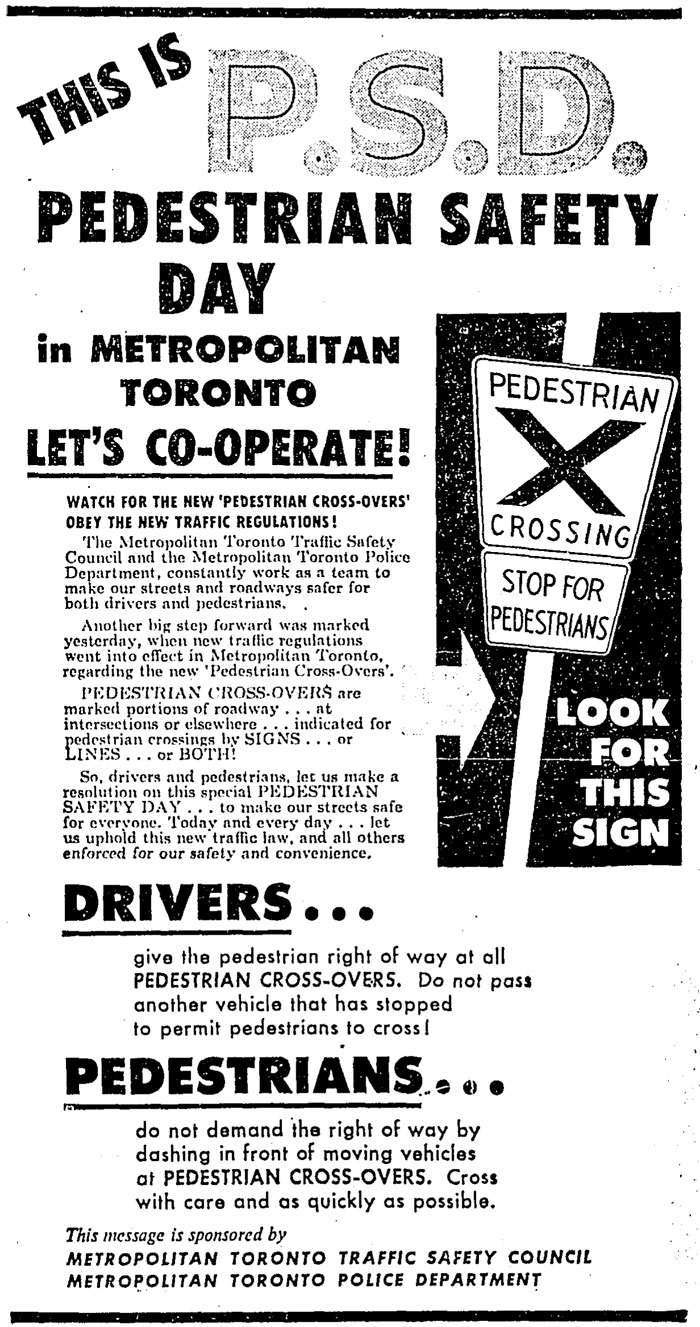

In 1958, in response to an increasing number of deaths, Toronto introduced its first marked crosswalks, giving pedestrians priority over cars at select locations and punishing those who entered the street elsewhere.

The crossings were minimalist affairs: just painted white lines on the road and signs that read “Pedestrian X Crossing” and “Stop for Pedestrians.” There were no lights, no zebra markings, and no instructions for walkers to point as they entered the road. As a result, drivers often ignored or failed to see the new features of the road.

In fact, the new “cross-overs,” as they called, weren’t much of a victory for people traveling on foot.

Metro Toronto hoped that forcing pedestrians into crosswalks and punishing those who tried to cross mid-block would improve safety by keeping people off the streets. Fines started at $5 for the first “jaywalking” offence, $10 for the second, and $20 every time after that, although judges were allowed to issue fines of up to $200.

“It’s simple,” said Sam Cass, Metropolitan Toronto’s head traffic engineer. “You play ball with me and I’ll play ball with you.”

Almost immediately it became clear the crosswalks weren’t perfect. Less than 24 hours after the official launch, 5-year-old Deborah Wark, walking home alone after visiting a neighbourhood candy store, was struck and killed at a crossing on Keele St. It was “pedestrian safety day,” and a police officer had left the intersection moments earlier.

Wark’s death caused a public outcry, but Cass said the crossings weren’t to blame. He said safety was a personal responsibility and that drivers needed to get used to yielding to pedestrians. Rather than improving the design, there were calls to cancel the fledgling crosswalk program entirely.

No changes were made, but deaths still occurred. Just days after Wark was hit, three people were killed by a truck at a crossing at Bathurst and Melrose.

Drivers complained parked vehicles blocked the warning signs and the white road markings became practically invisible at night or in the rain. Pedestrians walked into the street in frustration when drivers refused to yield, sometimes with disastrous consequences.

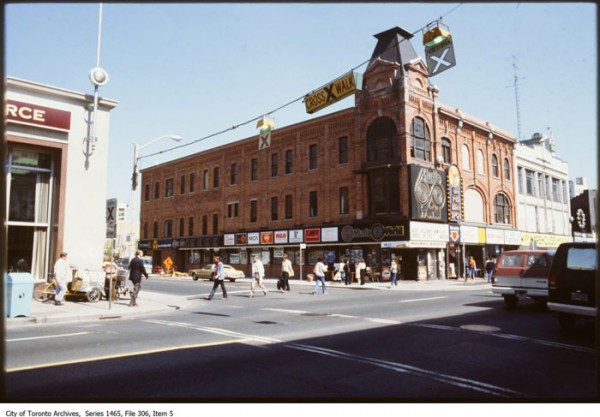

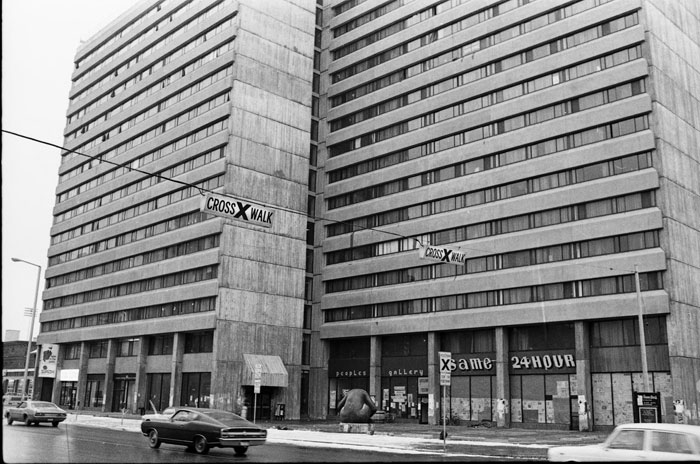

A year later, in an effort to make drivers more aware of crosswalks, Metro added advance warning signs and painted large Xs on the roadway. It was also around this time the “point your way to safety” signs appeared. Toronto City Council also called for flashing lights that could be controlled from the sidewalk, but the idea was rejected. Traffic experts said giving pedestrians control over the flow of traffic would lead to more accidents.

“Making the crosswalks more obvious does not make them any safer for pedestrians,” Cass said. “Accidents cannot be prevented with traffic signal or control devices,” he added later.

There were all kinds of ideas for improving Toronto’s crosswalks, many of them ridiculous. Red flags were handed out at an experimental crossing at Yonge and Gould in the summer of 1960 in the hope that the colours would better catch the attention of drivers. Coloured asphalt was tested on the 401 with a view to using it at crossings and other problem areas.

(Best of all, in the 1950s, cops would drive around berating bad drivers over a loudspeaker from inside an anonymous yellow panel truck. “You in the convertible, and you, sir, in the two-tone sedan, don’t you think you should allow the little girl to cross? She’s at a crosswalk, she has the right of way,” Constable Al Keates said on one occasion recorded by the Globe and Mail.)

Despite the high profile fatalities and public criticism, it appeared crossings were having a positive effect on the number of accidents. Traffic deaths dropped by almost a third in the eight months after they were unveiled, and by 1962 the numbers were continuing to trend downward. 58 people died in 1961, compared to 85 the year before crosswalks.

Lights did eventually appear in the form of fixed amber blinkers attached to concrete traffic islands, but there was no still no nighttime illuminations six years after the first crosswalks were installed. In 1964, Toronto mayor Philip Givens suggested adding rumble strips or “some sort of electrical impulse” (he didn’t explain further) to warn drivers of approaching crossings in addition to lights.

Cass, who had long opposed lights, said it would be hard to select a colour for crosswalks. Snow plows used blue, ambulances red, and traffic lights red, yellow, and green. “What about black,” Givens suggested. North York reeve James Service proposed a revolving light. Cass warned too many lights might distract drivers, but amber eventually won out.

Following a successful test of overhanging lights on the Danforth in 1966, Metro Toronto began illuminating crosswalks at night, but the arrival of pedestrian-controlled flashing lights wouldn’t come until 1988 when Ontario standardized crosswalks province-wide.

Today, it’s still not clear whether pedestrian crossings are completely safe. Go out onto the street, press the button, and no doubt several cars will zip past before traffic stops. At least one study has shown that, despite the addition of safety features, it is still safer to cross at an intersection rather than a mid-block crosswalk.

“If people think a marked crosswalk is going to stop traffic, they’re quite mistaken,” Raynald Marchand, manager of the traffic safety and training section at the Canadian Safety Council, told the Globe and Mail in 2002.

At least there are (legally speaking) no more jaywalkers.

4 comments

“…the arrival of pedestrian-controlled flashing lights wouldn’t come until 1988 when Ontario standardized crosswalks province-wide.”

I remember rather a lot of “pedestrian-controlled flashing light” crosswalks before 1988.

You might find this article of interest…….

When Pedestrians Ruled the Streets

http://www.smithsonian.com/innovation/when-pedestrians-ruled-streets-180953396/

Unfortunately traffic has become too important for pedestrian crossings, except on minor streets. In the suburbs, which is what we have built for many decades, and currently applies to at least 90% of the GTA, pedestrian crosswalks on arterials are considered unsafe. They do however add traffic lights for cars, which also often allow pedestrians to cross at the same time, often on one side of the street, in-between turning phases, for a few seconds, before the 30 second red signal (for pedestrians) begins.

Ah the good old days ,”5-year-old Deborah Wark, walking home alone after visiting a neighbourhood candy store, ”

Let your 5 year old walk anywhere alone now and you’ll be judged a terrible parent. Even though crime rates are at an all time low.