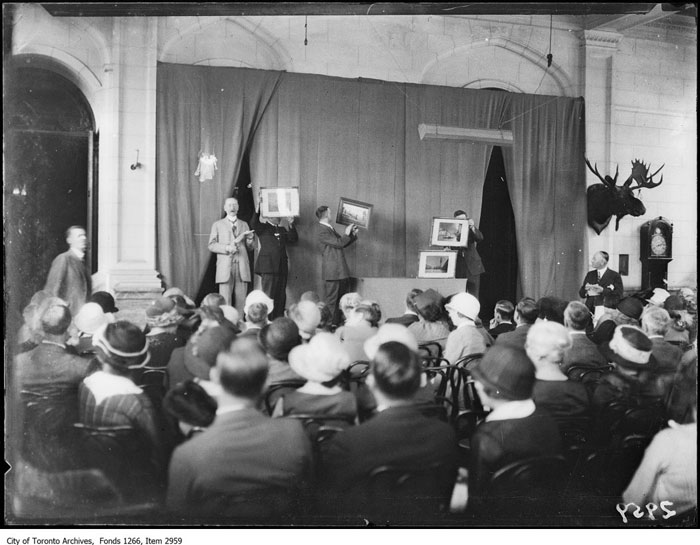

A carved marble fountain of child figures supporting a dolphin, a solid bronze buffalo head, and hundreds of champagne flutes, wine glasses, and ceramic dinnerware: almost everything in Casa Loma was up for grabs 91 years ago this week.

The empire of the home’s former millionaire owner, Sir Henry Pellatt, was rapidly disintegrating. Heavily in debt to the bank and his money tied up in real estate developments stalled due to the Great Depression, Pellatt was unceremoniously forced out of his hilltop mansion at Spadina and Davenport in 1924.

That summer he quit the 98-room palace with just three van loads of belongings. All the rest was for sale at knock-down prices.

A grandfather clock went for $155, a collection of garden vases were scooped up for $16 each, and two brass sundials were bought by a man from Detroit for $25. Even Pellatt’s bathroom scales went under the hammer, selling for $10.

“A Persian rug for the price of a doormat,” remarked Charles Henderson on the first day of the almost week-long auction.

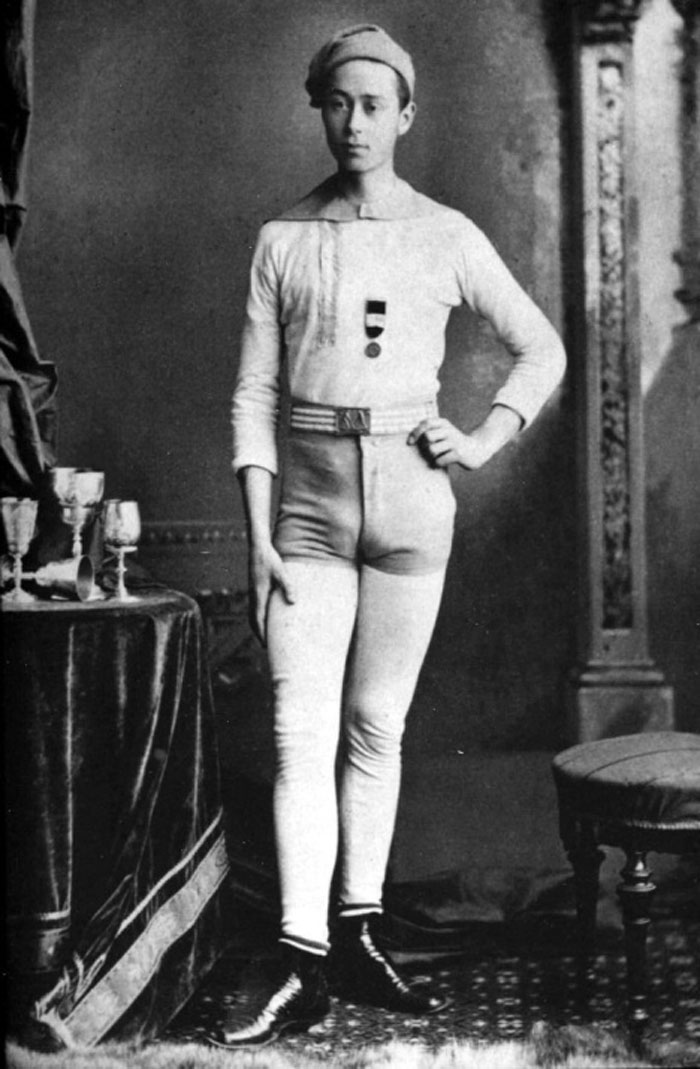

Born in Kingston, Ontario in 1859, Henry Mill Pellatt graduated from Upper Canada College aged 17 and joined his father’s stockbroking business. He shrewd investor from the outset, co-founded the Toronto Electric Light Co. in 1880s and helped secure the first contract to illuminate the streets of Toronto.

32 of the company’s giant arc lamps, which used the glow of electricity jumping between two carbon electrodes, were installed throughout downtown.

TELC was first utility company to harness the generating power of Niagara Falls and it was their electricity that powered Toronto’s earliest horseless streetcars. As the city rapidly expanded in the days before publicly-owned utilities, Pellatt’s first investment became a runaway success.

Parlaying his windfall into other electricity-related ventures, Pellatt and a consortium of other industry bigwigs formed tramway, light, and power companies in Sao Paolo and Rio de Janeiro that were later merged to form Brascan, now Brookfield Asset Management Inc.

In 1905, freshly knighted by Edward VII and enshrined as the leader of the Queen’s Own Rifles, a militia regiment he had joined aged 17, Pellatt began planing what would become his most famous contribution to Toronto.

Pellatt had been fascinated by castles since visiting Europe as a teen. According to author John Denison, the future king of Casa Loma sketched the castles of Switzerland, memorizing their dreaming towers and fairy tale architectural flourishes.

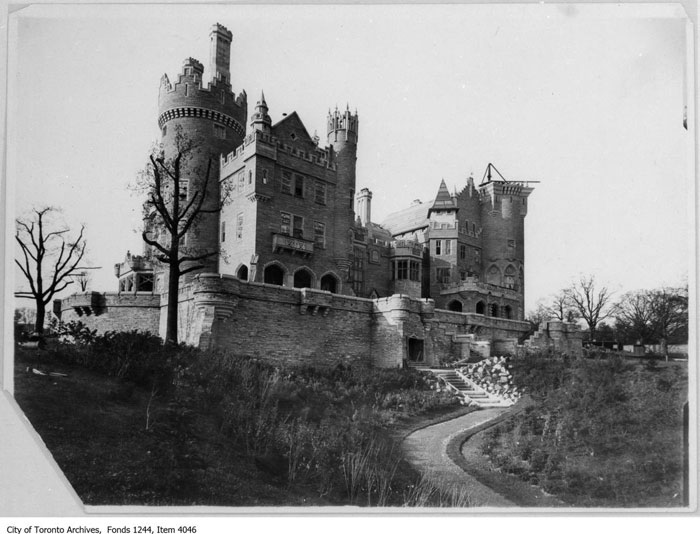

After securing a large tract of land under his wife’s name atop the ridge north of Davenport Rd., work on the home’s Credit Valley stone stable building began in 1905.

The floors were made of Spanish tile and specially laid to provide good grip for hooves. The stalls were made of mahogany. Writer Denison notes that each of Pellatt’s horses had its name displayed in eighteen carat gold letters. The bill: $250,000, or about $5.5 million in today’s money.

The equine quarters were ostentatious, but the main house was positively absurd. Designed by E. J. Lennox, the architect who designed Old City Hall, the blueprint for the largest private residence in Canada called for 98 rooms, 30 bathrooms, three bowling alleys, an indoor swimming pool, and rifle range. It was to have its own internal telephone system and built-in vacuum system for cleaning.

The halls were floored with solid mahogany and bear skin rugs. The 10,000-book library had the Pellatt family coat of arms carved into the ceiling, the doors from the dining room to the conservatory were made of solid bronze and cost $10,000 ($215,000 in 2015) each. Henry’s study contained a replica of Napoleon’s desk and had two secret passages: one leading to the basement vault another to the second floor.

In total, the project cost Pellatt about $3.5 million—about $75 million in today’s money.

Work stopped on Casa Loma at the outbreak of the first world war, but it was finished enough to allow the owners to move in and start entertaining. Henry and Mary’s frequent parties were legendary and attended by prominent Toronto worthies, such as the Eatons.

Trouble began to surface as the first world war drew to a close. Pellatt’s business debts were mounting and land he had bought in the Cedarvale area had failed increase in value. By 1923, less than 10 years after moving into Casa Loma, Pellatt owed $1.7 million ($24.2 million, 2015) to the Home Bank, which went bankrupt that year amid financial irregularities.

The property tax alone on the mansion was $1,000 a month. Fuel costs were $15,000 a year and the total annual cost of servicing the property was $22,000—$313,000 in 2015. With the couple’s cash flow drying up, Lady Pellatt died of a heart attack in April 1924. A short time later, Henry cut his loses and allowed the City of Toronto to seize his dream home for backed taxes. The contents he decided to auction off in an effort to cover his debts.

The collection of luxury items, valued at $1.5 million, was snapped up for roughly $250,000. The $75,000 pipe organ that once graced the property, fetched just $40, although the auctioneer did serenade the crowd with a rendition of Auld Lang Syne.

Countless works of art went for a song, as did bolts of fabric, Chesterfields, arm chairs, Chippendale furniture,

“It is a sale that breaks my heart,” Pellatt told the Toronto Star. “The process is something like getting a tooth pulled—once over, one proceeds to forget all about it.”

Divested of his home and a large part of his fortune, Pellatt lived out the remainder of his years mostly out from the public eye. Casa Loma, meanwhile, sat vacant. There were plans to convert it into a luxury hotel, even a high school, a convent, and an Orange Lodge, but it was ultimately it was the Kiwanis Club of West Toronto who took over in 1936 and turned it into a tourist attraction.

Pellatt died in 1939 having never regained his status as Toronto’s most extravagant millionaire, but the funeral at least lived up to his grand reputation.

Thousands lined the cold winter streets for the largest military funeral in the city’s history.

3 comments

“Heavily in debt to the bank and his money tied up in real estate developments stalled due to the Great Depression, Pellatt was unceremoniously forced out of his hilltop mansion at Spadina and Davenport in 1924.”

Kevin’s comment: The Great Depression is generally reckoned to have begun with the stock market crash of October 1929.

In debt? What happened? People stopped using electricity?

Even during and after the war I would expect people to use electricity..

Pellatt owed money to many banks, often using the same properties as collateral. With an income of only $66,000 in 1920 and debts of over 3 million, he transferred his part of the electricity Co. to his business partner Sir William Mackenzie, from whom he had borrowed 1 million for Casa Loma. Shortly thereafter, he managed to bring down the Home Bank and thereby created much of the regulatory framework that has prevented a Canadian bank failure since.

Discovering what money was Pellatt’s and what was borrowed is difficult, but two good sources are R. B. Fleming, The railway king of Canada: Sir William Mackenzie, 1849–1923 and

Carlie Oreskovich Sir Henry Pellatt, the King of Casa Loma.

Pellatt’s failure was not the result of the Great Depression, his showmanship based on borrowed money and disregard for the effects upon others was part of the business ethos that led to the Depression.