Not for the first time, and certainly not the last, I came across a family of tourists in the subway the other day, trying to figure out how to get to Casa Loma — Toronto’s second best known landmark and arguably the one whose location is most likely to confound a visitor with a guidebook.

I didn’t ask, but there’s a good chance these people were in town for the Pan Am/Parapan Games, which are set to begin Friday.

It should be a red letter day for the Centre of the Known Universe: after almost two decades of trying, we will finally get a chance to strut our stuff on the world stage, or at least the hemispheric stage.

At such sought-after sports extravaganzas, it often seems that organizers and civic officials are at least as interested in the impression they convey to the international media as they are with welcoming the athletes. Consequently, the city’s well-documented self-involvement will re-surface: how do others see us, and what is the story we have to tell?

If you’re in the destination marketing business, and are pondering the question of what all those hordes of Pan Am tourists should do when they’re not taking in the events, you may find yourself thinking, with relief, about the new Ripley’s Aquarium, the upbeat reviews for Kinky Boots, or the cool cultural sophistication of the Aga Khan Museum. After a long dry spell, we’ve replenished our attraction “inventory,” as they say in the tourist business.

There are, of course, the restaurants and the museums, the waterfront parks and the cultural attractions, as well as the groovy neighbourhoods that warrant a shout out in the tourist guides — Kensington, Queen West, Leslieville perhaps.

But Toronto still does a lousy job when it comes to telling visitors about its stories, and its past. Besides Casa Loma (dubbed by the landmark’s new managers as “Canada’s majestic castle”), the Distillery District, and St. Lawrence Market, it’s as if the city — which bulldozed so much of its 19th century built form after World War II — has no history, or at least none worth sharing with guests.

Tourism, of course, isn’t always driven by historical curiosity, but there’s no doubt that heritage buildings and districts — apart from all their other urban merits — serve as powerful magnets for visitors. As a 2009 Ontario government study points out, one survey showed that over half of Americans who took a pleasure trip in 2004 or 2005 visited a historic site, museum, or gallery. No one goes to Paris to visit the suburbs, and so on. (The City of Toronto’s salesmanship on this point leaves much to be desired. As this page on the City’s walking tour listing puts it, “Think that historic sites are boring? Think again. Toronto is filled with National Historic Sites that are still hip and happening!”)

The new-ish Fort York Visitor Centre begins to address the city’s self-inflicted amnesia, but many other cities have gone much further in finding imaginative ways to share the stories of historic areas, including the ones that aren’t necessarily filled with old mansions or designated structures.

For example, Detour, a San Francisco firm, has developed a line of audio walking tours (you download them onto your device) of some of the city’s most atmospheric neighbourhoods, including more outré places like The Tenderloin, which contain tons of social history.

In other cases, physical markers connote historical events that have left no detectable residue. Across Europe, for example, artist Gunter Demnig has been installing “stumble stones” on the sidewalks where Holocaust victims last lived before being deported; the small bricks are engraved with the name of the victim. A similar project has been underway in New York for the past decade, as volunteers use chalk to mark the homes of victims on each anniversary of the 1911 Triangle Shirtwaist Co. fire.

Elsewhere in New York, Place Matters (a joint venture between City Lore and the Municipal Art Society) has built up an eclectic selection of highly informative online walking tours — for example, this one on vernacular architecture in lower Manhattan — that include historical information and archival images presented in a slideshow format well suited to portable devices.

New York is also home to the Tenement Museum, which has become one of the city’s most visited tourist attractions. Its very existence offers a powerful critique of what sorts of buildings are historically valuable, not just for tourism but also as a means of creating a heightened awareness of long-vanished communities that had little money and plenty of hardship.

The Lower Eastside (LES) has been the subject of other place-making efforts meant to generate a new sort of consciousness about the way life was lived in a part of the city that became synonymous with crowding, poverty, and poor working conditions.

Preservation and public history expert Chris Neville, an adjunct professor at Columbia University, was part of an LES sign mapping project that installed large placards on private buildings in the LES. Each had an archival photo taken at or close to the location of the sign, as well as multi-lingual quotes from residents who’d lived in the area. The approach, Neville says, directly addresses the question of whose history is being told, but it also cultivates historical sensibility — an awareness, in the viewer, that they’re standing in a place where others have walked and worked, lived and died.

That sense of place, he adds, can exist, or be fostered, in areas where original or earlier buildings no longer exist. “Just as there is a story to how things got built up,” he says, “there’s a story about how things got erased.”

In Toronto, of course, we’ve erased many things, and we tend not to talk about them after they’re gone. Having spent the past two years working on an anthology about The Ward, the “arrival city” that predates Nathan Phillips Square, I have found myself wondering what the City should do to create a better awareness of an area whose story played an outsized role in the evolution of contemporary multi-cultural Toronto. The same question could be posed about Parkdale, the Junction and other historically important communities experiencing dramatic transformations.

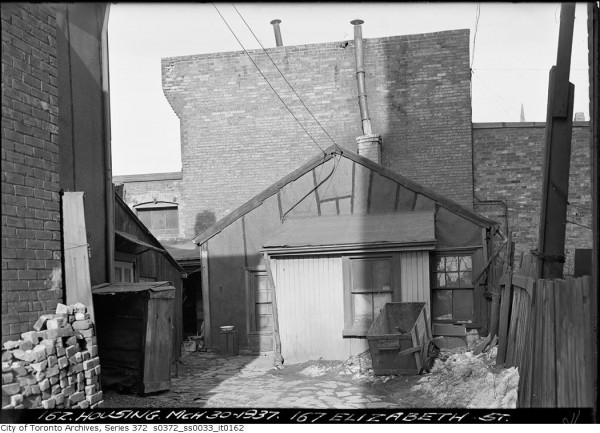

Almost nothing remains of The Ward’s original built form; the area fell victim to expropriation and land assembly after World War II, so only a handful of old or historic buildings remain. So here’s my question: how should we mark its role — indeed, the Ward’s very existence — at the heart of the city that now surrounds it?

The Ward, after all, is Toronto’s Lower East Side. But no one — tourists and residents alike — knows where it is.

photo from City of Toronto Archives

4 comments

An improved, comprehensive museum at Toronto City Hall! Please don’t exclude the suburbs and our amazing living history.

Why don’t we do something here? I’m a designer and media artist, I’d love to get involved with a project like the ones you mention in our home town.

Hi John

Thanks for your special in today’s Star on the Gerrard village. You mentioned my mom’s cousin Daisy, Pauline Redsell-Fediow. I have researched what I could find from the AGO archives on her, and have seen her sculpture bust in the Harbord neighbourhood park. She did a lovely drawing of my mother, born Redsell, which vanished long ago. I would love to find other pieces by her.

Frank Godfrey

Murmur is wonderful (murmurtoronto.ca), and the new Ward Museum project has tremendous promise (http://www.wardmuseum.ca/) but we’re lacking serious bricks and mortar city history venues, and even these projects are extremely poorly promoted. Plus, as grassroots ventures, their future is always in question.