She was found beneath a coat hidden under dogwood and sweet clover. Toronto parks department employee Harry Lemon saw her shoe first, carelessly discarded near the shore of Long Pond on Centre Island in the late summer of 1940.

Walking over scrubland behind the water treatment plant, Lemon discovered more items. A silver pencil, a white handkerchief, a garter, a purse. “There was no path, but I could see where the weeds and long grass had been pressed down.” he recalled.

“I knew at once it was a body.”

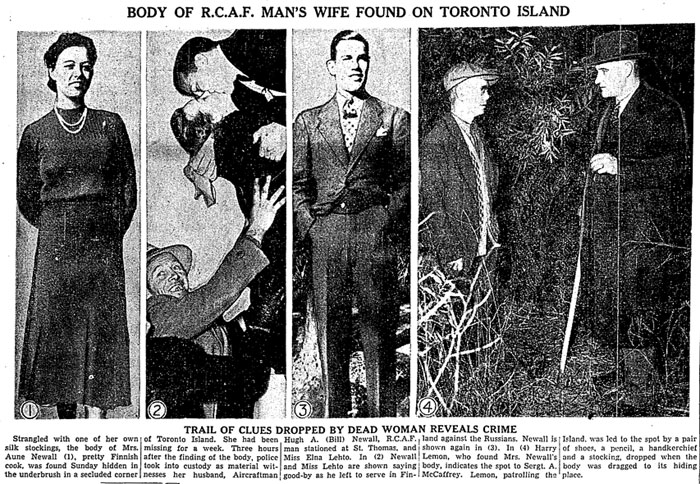

22-year-old Aune Newell had been strangled. One of her silk stockings had been used as a ligature around her neck. The Toronto Star reported that Newell had been missing from her home at a Grange Ave. boarding house for a week prior to being discovered.

Her estranged husband, 27-year-old Hugh Newell, a member of the Royal Canadian Air Force who went by the nickname “Bill,” and Elna Lehto, 24, his new girlfriend, were taken into custody as material witnesses. Local media latched onto the story, dubbing it the “silk stocking murder.”

Early suspicions centred around Bill. He collected Aune from her home the day she vanished. When she failed to return that evening, Bill told Aune’s roommate that his wife had suddenly decided to go to Vineland to see their two-year-old son, Billie, who was living with an aunt.

Aune didn’t look typically Finnish. She had dark hair and eyes, and the Toronto Star said she was slim and pretty. She was well-known in Toronto’s Finnish community and was a regular at a social club on Huron St., where she liked to dance. Her friends affectionately called her “Spooky.”

Bill Newell also had dark features. A powerfully-built narcissist who excelled at pole vault, he was already married when he met Aune, though by the time his first divorce was finalized he and Aune were already sharing a house and raising their six-month-old son.

His commitment to Aune didn’t last. Soon after the pair got together, Bill began courting Elna Lehto, another woman of Finnish extraction. It was at this time in 1940 that Bill joined a group of Canadian-Finnish expats headed back to their homeland in an attempt to repel the invading Russians.

The Toronto Star even published a photo of Bill kissing Lehto goodbye as his train departed the city.

Bill stayed in the conflict long enough to lose an eye, but returned to Toronto within a year. In August, 1940, he joined the Royal Canadian Air Force and was posted to Brandon, Manitoba. It was at this point the friction between Bill and Aune began to noticeably increase.

Because the pair had never divorced, Bill’s military dependents’ allowance automatically went to his estranged wife and son, much to his annoyance. In an attempt to obtain a divorce and re-route the money to Lehto, Bill was reposted to St. Thomas, Ontario, but it appeared Aune staunchly rejected the idea.

Apparently undeterred, Bill attempted to sweeten Aune with frequent visits. On Sept. 29, 1940, he called at Aune’s rooming house to take her out for lunch. “I’ll be back in about an hour,” she told her roommate.

Several people came heartbreakingly close to interrupting Aune’s murder.

James Dibble, a foreman at the Island incinerator, near where the body was discovered, told the papers he had seen two people walking a seldom used trail the day Aune disappeared.

“I saw a girl and a man walking through the field. The sweet clover grows nearly six feet high in some places and it was difficult to see them at first,” he said. “There are a lot of pheasants there, and I watch to prevent dogs disturbing them, which is how I noticed the young couple.”

Dibble said he stopped to watch some fisherman on the shore and when he looked again the pair had vanished. Later, he reported hearing a girl screaming loudly and investigated the sound in his canoe. “I pulled my canoe up on the bank not 50 feet from where the body was found today,” he said.

Finding nothing, he retreated.

Another may have seen the murder in process. Marion Maynes, an Island resident, saw a young woman sitting on the shore of Long Pond, motionless. “She was just staring out into space. Just sitting, staring.”

When Aune was eventually found, she was lying on her side, arms folded beneath her chest, legs tucked up against her body, possibly in an attempt to hide her from view.

A team of police officers led by Sergeant McCaffrey scoured the area for clues but didn’t find much. No sign of a struggle, no hint of where the killing had taken place.

They did find a thread caught on a bush.

Following a lunch at a diner on Adelaide St., Bill suggested he and Aune walk in the pleasant Fall weather on Centre Island. On the way to the ferry dock, Aune’s former boss saw the pair from her car and waved—a mundane interaction that would later prove critical.

After returning to the city, Bill told police he went to a swimming pool on Manning Ave. An attendant there remembered someone entering with an expired pass, though he couldn’t be sure if the name on the card was Newman or Newell.

Bill’s behaviour under police questioning was suspicious. He was overly anxious that police discover a letter he had written to Aune two days after she had disappeared in which he asked for custody of their son.

More telling, however, were several angry notes Bill had written to his new partner, Elna Lehto, in which he ranted about Aune’s ability to collect the allowance his work provided.

“Try to control your temper … banish those ugly thoughts from your mind,” Lehto wrote in response to a letter police tantalizingly could not find.

Convinced they had a case, police charged Bill Newell with Aune’s murder.

At trial, the Crown presented mud and seeds removed from a pair of Bill’s boots as evidence he had been present at Aune’s murder. A botanist, soil expert, and geologist all testified. A fibre expert compared the light blue thread found by Sergeant McCaffrey to Bill’s Air Force uniform, finding them similar but not a conclusive match.

Elna Lehto spoke in defence of her partner.

The most shocking revelation came from an Air Force flight sergeant who had visited Bill in jail. Lloyd Rawlins testified how his colleague had offered a detailed and unsolicited account of how Aune’s murder might have occurred.

“It could be done by getting behind a person, putting the arms around the body, turning the knuckle in here [indicating the region of the heart] and exerting pressure so the person would be rendered unconscious,” he told Rawlins. The fatal stocking ligature could have been applied while Aune was unconscious, Bill added.

The evidence failed to persuade the jury either way, however, and the judge declared a mistrial. A second trial, punctuated by allegations of jailhouse beatings and the defendant’s aggressive outbursts, also resulted in a hung jury.

During the third trial, the prosecution scored a stunning coup. Elna Lehto, who had previously testified for the defence, agreed to switch sides. Bill Newell flushed red and appeared ready to boil over with rage as she was introduced as a surprise witness.

Lehto told the rapt court how Bill had returned home with cuts on his face the evening of Aune’s disappearance. With nothing else to hand, she’d filled the wounds with antiseptic cold cream.

Aune’s former boss, who saw the pair from her car, and Marion Maynes, the woman who recalled seeing a person matching Aune’s description sitting motionless on the shore of the Island, testified for the first time, too.

Swayed by the slew of new evidence, a third jury found Bill Newell guilty of Aune’s murder. The judge, Mr. Justice Hope, said he should be hanged at the Don Jail.

“I am not guilty,” an uncharacteristically calm Bill told the court before being led away. “I never killed by wife and would not. I never killed anybody.”

His avenues for appeal exhausted, Bill Newell was led to the gallows in the cold early morning hours of Feb. 12, 1942. In the mistaken belief he would be spared if he survived, Bill had worked hard to strengthen his neck muscles in the days before the execution.

Instead, it just prolonged the inevitable.