The CN Tower is one of the most important buildings ever constructed in Canada.

Like it or loathe it, the absurd, 553-metre concrete tower, which opened to the public 40 years ago this Sunday, is the defining structure of this city.

For outsiders, it’s the building that separates the Toronto skyline from those of other world cities; for people who live close to the core, it’s a constant presence, looming large in the background like a benevolent giant.

Despite its monumentality and popularity with tourists, the CN Tower isn’t really a building the people of Toronto think about much. For that reason, not many people know that the city’s most famous building is actually a relic of a much bigger development proposal.

The origins of the CN Tower lie in the abortive Metro Centre proposal for downtown Toronto.

First unveiled to the public in December, 1968, the $1 billion joint plan by Canadian Pacific and Canadian National to convert their sprawling surplus railway lands between Yonge, Bathurst, and Front streets into a new live-work neighbourhood was the largest revitalization scheme ever planned in North America.

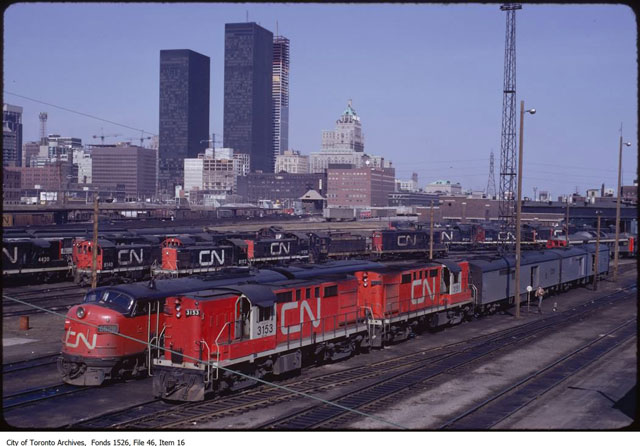

The CN/CP land in question was a mix of sooty sidings, roundhouses, and storage buildings built after the turn of the century to service the waterfront wharves and docks. By 1960, the tracks covered approximately 190-acres, and stretched as far north as King and Simcoe streets.

In fact, at the time, almost all the land between Front Street and Queens Quay was occupied by marshalling yards and service facilities.

With newer, high-capacity freight facilities available for Canadian Pacific and Canadian National available outside the core and passengers switching to cars and planes to travel long distances, the rail companies saw a chance to exploit the lucrative development potential of their central Toronto land holdings.

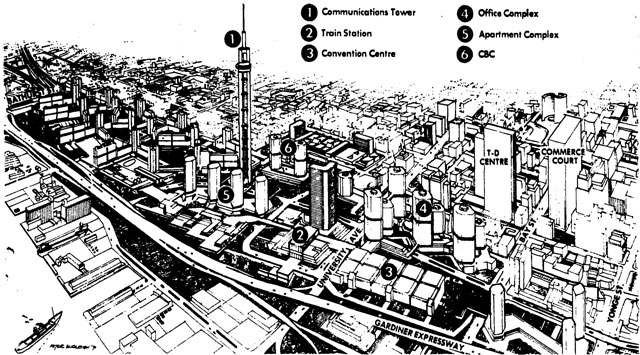

Designed primarily by architect John Andrews—the Australian-born head of the University of Toronto department of architecture—Metro Centre was to house 20,000 people in a mix of apartment buildings and terraced homes, provide 418,000 square metres of new office space, and add 55,750 square metres of commercial property to the city.

The development was divided into four distinct zones: residential, transportation, office-commercial, and communications and broadcasting.

At the heart of the transportation zone, designers marked out a massive new transit centre for buses, GO Trains, and TTC rapid transit near Yonge and Queens Quay to be serviced by a three-stop, southerly extension of the Yonge subway line and a lengthening of University Avenue.

One of the most striking features of Metro Centre was the separation of automobile, pedestrian, and transit traffic. Surface streets, including a portion of University Avenue, were to be broken up into multiple levels, with people on foot mostly below the surface in a skylit mall system similar to today’s PATH network.

Not everyone was a fan of the idea.

“As a means of separating vehicular and pedestrian traffic, it works fine,” wrote architecture critic Harvey Cowan in the Star. “However, once you’ve moved below the surface vehicular level, to the pedestrian mall, you will lose visual contact with the lakefront.”

“One of the most unique aspects of Metro Centre is its physical location, within sight of Lake Ontario. This location should be exploited for pedestrians, too,” Cowan wrote.

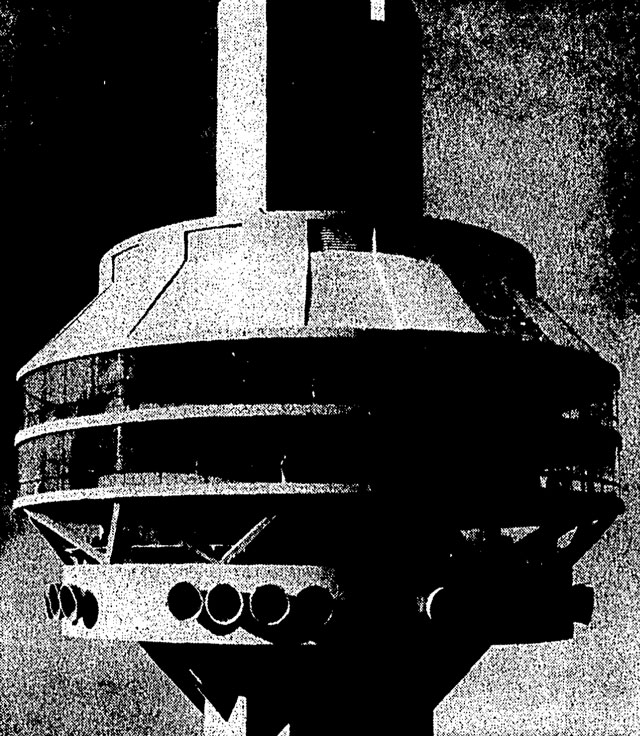

The most eyebrow-raising feature of Metro Centre, however, was a massive freestanding transmitting tower with a restaurant and observation deck perched 365 metres feet in the air.

The unnamed structure consisted of three separate towers clustered together and linked via pedestrian bridges. The observation level was positioned near the top of the tripod made by the supporting towers.

“This would be Canada’s tallest structure of any kind and one of the tallest self-supporting structures in the world,” the Toronto Star announced its readers. At the tower’s base was to be a new CBC English language headquarters and broadcast centre.

“Metro Centre will transform what is regarded as an eyesore into a great asset for Toronto,” the Globe and Mail reported. “In an unparalleled feat of urban design … the entire area from Yonge Street to Bathurst Street south of Front Street will be covered over to make it possible to build a new downtown Toronto.”

Work was anticipated to start Fall of 1969.

As is patently obvious, things hit a snag. Though city council and the Ontario Municipal Board did approve Metro Centre, the planning process stalled over the possible demolition of Union Station. Under the CN/CP proposal, the historic station would have made way for office towers and its function as a transport terminal shifted to the new facility closer to the lake.

The death knell came in May, 1975 when premier Bill Davis announced Union Station would remain downtown Toronto’s transit centre, a decision that fundamentally spoiled the Metro Centre plan to shift the rail corridor south. Coupled with a new city council suspicious of mega projects, the grand idea went mostly in the trash.

One element, however, remain unaffected.

Construction on the CN Tower began on the site of a CN railway siding in February, 1973. Gone was the three-tower design unveiled in the 1960s, replaced by the one familiar today, and also gone was Canadian Pacific. The railway quit the project before work broke ground, leaving Canadian National to fund the tower alone.

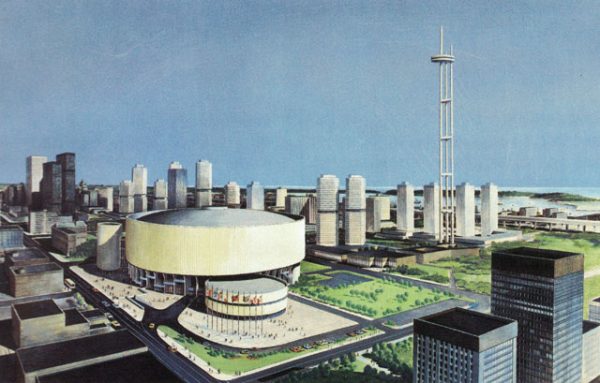

The final blueprint looked much closer to today’s tower, but it had several features that didn’t make it to fruition. The base of the tower was planted in a reflecting and skating pool surrounded by terraced slopes of boutiques and restaurants, and there was dense tree coverage in the area now occupied by the Skydome.

The main pod was different, too. The radome—the white donut-shaped piece under the observation level—was not included. Instead, it appeared the broadcast equipment was mounted to the outside.

At 553.3 metres, the tower was to become the tallest freestanding structure in the world, and there were naturally concerns about allowing such a enormous project to go ahead.

Aviation experts said the tower would pose a hazard to aircraft using the Island, Toronto International, and even Hamilton airports. “Sooner or later an aircraft is bound to strike it, possibly killing people in the tower and on the ground as well as those in the aircraft,” the Canadian Owners and Pilots Association said in a statement to the press.

Migratory birds were also a factor in the planning process. Toronto is located on a vital travel route for birds, and critics of the tower said it could cause death or injury to airborne flocks. Before construction began, city alderman (and future mayor) David Crombie pushed unsuccessfully for the height of the tower to be cut by two thirds in response to those concerns.

(Interestingly, the problematic height of the tower was selected “arbitrarily,” according to N. J. MacMillan, chairman and president of CN. He told the Globe and Mail the primary reason for selecting 553 metres was to keep the radio and television transmitters a suitable distance apart.)

The main shaft of the CN Tower began to rise in the summer of 1973. Rather than using large pre-cast forms, construction workers poured concrete in individual layers and fastened the whole thing together with cables. At the Skypod level, the concrete stopped, and the white transmitter antenna and lightning rod were bolted in place.

During removal of a crane used during assembly of the tower’s concrete core, a 10-ton Sikorsky transport helicopter became accidentally tethered to the tower when a section of boom became seized in place. A frantic scramble to free the aircraft before it ran out of fuel was only successful when, with 14 minutes to spare, workers managed to melt the offending metalwork.

On June 26, 1976 the finished CN Tower opened to the public with a ceremony based almost entirely on height jokes. 6 foot, 5 inch finance minister Donald Macdonald, stilt walkers, and two random tall people—7 foot Thornhill kitchen equipment maker Roger Tickner and 6 foot, 3 1/4 inch Paula Lishman—helped active the exterior lights as the clock struck midnight.

Even Joe Hall, the Star reporter sent to cover the event, was tall: 6 foot, 4 1/4 inches.

“The only place higher that man’s ever stood on a stationary base, except for a mountain peak, is the moon,” wrote Paul King in a special pull out section of the Toronto Star printed on opening day.

“On Earth, man can climb no higher in any enclosed structure.”

3 comments

I must commend Chris for the great work he has done to bring more recognition, awareness and understanding to today’s generation about the long forgotten and failed Metro Centre, plus its sibling CN Tower project. I have studied both extensively, as they form the basis of my CN Tower historical project. While I explicitly do not focus on the public awareness of Metro Centre, please take an hour to visit & read over the content of http://www.PastAndFutureHistory.com. It provides “bite sized” snippets of the tower’s entire history, from 1957 through to 1976.

Note the typo, describing the Metro Centre tower as “365 metres feet” in the air.

It’s interesting that, while we didn’t get Metro Centre as envisioned, we did get the convention Centre, telecom tower, mixed use live work areas (City place & Southcore), and the CBC Broadcasting Centre.

I’ve often wondered if it were possible to break up Line 1 at Union and extend the University-Spadina portion of the line south into the Harbourfront area and east to serve the East Bayfront, and extend the Yonge portion of the line west along Front Street to the Exhibition.

I was 10 yrs.old when they started to build the Tower. But l remember my oldest brother driving me down there one day.l remember It was just a lot of concrete going up and up. They weren’t up to the dome/restaurant yet. I also remember train tracks everywhere and a roundabout. Never seen anything like it built since. Maybe Skydome’s construction. With it’s moveable roof was next for Toronto.Good memories….